Kristiina Kangaspunta

This paper examines the successes and setbacks in the criminal justice response to trafficking in persons. While today, the majority of countries have passed specific legislation criminalising human trafficking in response to the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, there are still very few convictions of trafficking. Using currently available knowledge, this paper discusses four possible reasons for low conviction rates. Further, the paper suggests that due to the heavy dependency on victim testimonies when prosecuting trafficking in persons crimes, members of criminal organisations that are easily identifiable by victims may face criminal charges more frequently than other members of the criminal group, particularly those in positions of greater responsibility who profit the most from the criminal activities. In this context, the exceptionally high number of women among convicted offenders is explored.

Keywords: trafficking in persons, criminal justice framework, legislation, convictions, Nigerian organised crime, female traffickers

Please cite this article as: K Kangaspunta, ‘Was Trafficking in Persons Really Criminalised?’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 4, 2015, pp. 80—97, www.antitraffickingreview.org

Fifteen years ago, when the first anti-human trafficking initiatives were launched by international organisations, we practitioners would hear comments like: ‘why is the United Nations (UN) interested in prostitution?’ or ‘these so-called victims left the country voluntarily, it is their own fault’, which showed the ignorance and lack of understanding of the nature of trafficking in persons at that time. Since then, awareness of human trafficking has increased vastly and the professionalism in dealing with the issue has improved in most countries. However, there are still many open issues with regard to preventing and combating trafficking crimes. For instance, has the increasing awareness and professionalism also translated into success in addressing cases of trafficking in persons? Are we currently more efficient in detecting trafficking cases, protecting victims’ rights and preventing people from being victimised? Have anti-trafficking activities had negative impacts on some people? And have we reached a point where we can say that we are properly sanctioning the commission of trafficking offences in a way that takes into account the gravity of these crimes? This article will attempt to respond in particular to the last question based on the knowledge that we have today regarding criminal justice responses. While recognising that the criminal justice response must be accompanied by a larger effort to prevent trafficking and assist victims, this article focuses on successes and problems in this particular field. At the current time, a large majority of countries in the world have established a criminal justice framework to deal with trafficking in persons, and therefore it is useful to discuss whether this framework has been successfully used to respond to trafficking.

The adoption of the Trafficking Protocol1 in 2000 and its entry into force in 2003 demonstrated the political will of the international community to address trafficking in persons. States Parties of the Protocol are obliged to criminalise trafficking, either as a single offence or a combination of offences.2 The provision obligating States to criminalise trafficking in persons directly references the internationally agreed-upon definition of trafficking presented in Article 3 of the Protocol3 creating a standard for criminalisation.

Yet, the Trafficking Protocol has been criticised because it emphasises the law enforcement response over the protection and support of victims’ rights4 (e.g. while this argumentation usually cannot be denied, it should be kept in mind that the Trafficking Protocol supplements the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, which is of course, a crime treaty, with the main objective being the improvement of international cooperation mechanisms to prevent and combat transnational organised crime. Ratification of the Convention is a pre-condition to ratify the Trafficking Protocol, which roots the Protocol in the criminal law framework. Obviously, this framework has had an impact not only on victims and offenders as operators in the criminal justice system, but has also shaped the policies closely related to trafficking such as migration and prostitution policies.5 Treaties elaborated subsequent to the Protocol, such as the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings,6 do not have the same sort of connection to the criminal justice framework, which makes it possible for them to operate primarily in the human rights or other frameworks.

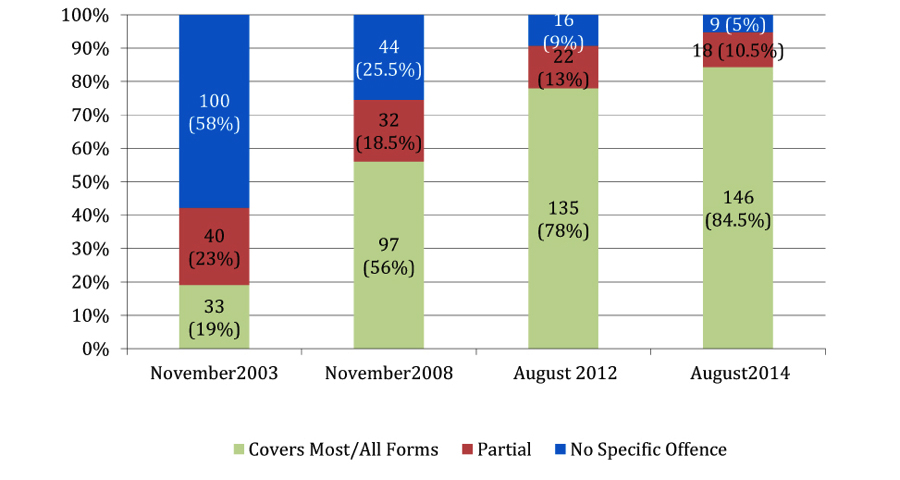

The Trafficking Protocol entered into force in 2003. Before that, many countries either had partial legislation that addressed only some forms of trafficking in persons or some victims, or did not have any legislation at all. Particularly male victims were absent from trafficking definitions and often only sexual exploitation was criminalised. Encouraged by the Protocol, the number of countries that introduced the crime of trafficking in persons into their penal code increased sharply after 2003 as shown in Figure 1.

Currently,7 only nine countries (out of the 173 countries that were analysed by UN Office on Drugs and Crime’s (UNODC) 2014 ‘Global Report on Trafficking in Persons’) do not have any specific legislation against trafficking in persons and 146 countries criminalise all aspects of trafficking in persons as explicitly listed in the Trafficking Protocol. When the population size of those countries that do not have special legislation or only have partial legislation against trafficking in persons is reviewed, we can see that about one-third of the world's population, consisting of around two billion people, live in a situation where trafficking is not criminalised as required by the Trafficking Protocol.8 This situation combined with a very low number of convictions makes trafficking in persons a crime of vast impunity.

Figure 1. Criminalisation of trafficking in persons with a specific offence, share and number of countries, 2003—2014

Source: UNODC 2014

In some countries, the use of non-specific criminal offences to prosecute cases of trafficking in persons is possible, including those against sexual violence, pimping, kidnapping, smuggling of migrants or others. However, for States Parties of the Trafficking Protocol in particular, there are serious drawbacks to using a non-specific criminal offence to address trafficking in persons. For instance, if trafficking legislation is in compliance with international treaty obligations, it will include the protection and assistance measures specifically designed for victims of trafficking in persons. Non-specific criminal offences will most likely not have any such provisions. As a result, the use of non-specific legislation will lead to a situation in which trafficking victims may not have proper access to support and protection services that are specifically developed for them. There are also other serious drawbacks to not using trafficking specific legislation based on the Trafficking Protocol, such as not having a basis to extradite suspects, to use mutual legal assistance to gather evidence, to confiscate proceeds of crime and to prosecute organised crime groups for money laundering.

At the regional level, the countries of North and Central America as well as Europe and Central Asia currently have legislation that is in compliance with the Trafficking Protocol and criminalises most or all forms of trafficking. Five countries in the Caribbean and South America lack specific legislation or have partial legislation against trafficking in persons. The situation is similar in South Asia, East Asia and the Pacific where four countries have either not criminalised human trafficking or have criminalised it only partially. The situation is most worrying in Sub-Saharan Africa where fourteen countries have no or partial legislation on trafficking in persons. In North Africa and Middle East, there are three countries that have not criminalised trafficking in persons.9

Criminalisation of trafficking in persons has been an important step for many countries to demonstrate that trafficking will not be accepted. It also brings human trafficking into the official criminal justice system, necessitating an allocation of resources to investigate the crime as well as prosecute, convict and sanction the traffickers. In many countries, the importance of a victim’s rights-centered approach has been acknowledged in the development of policies, and criminal justice responses have been complemented by victim protection and support schemes. However, implementation of these schemes has proven to be difficult and victims in many countries still may not have access to appropriate protection and support measures.10 Hopefully, limited resources combined with increasing needs will not force countries to choose between enforcing the legislation and protecting and assisting the victims.

The Trafficking Protocol clearly created a push for new, more comprehensive legislation addressing trafficking in persons. However, legislation remains a rather symbolic act against trafficking in persons, only signifying a moral standard against the crime, unless it is implemented. The real intolerance against human trafficking should be demonstrated by holding criminals liable to sanctions that take into account the gravity of human trafficking offences combined with proper compensation to victims of trafficking.

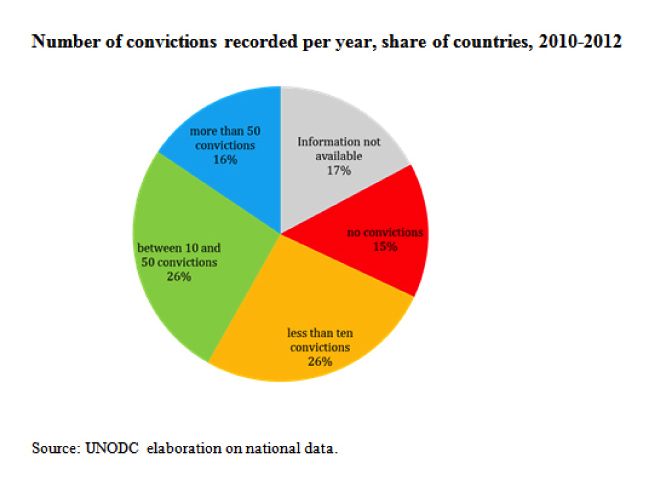

Unlike the great push to enact legislation against trafficking in persons after the entry into force of the Protocol, conviction records have remained stubbornly low since 2003. In fact, in 60–77% of countries, there were no major changes in this number between 2003 and 2012. On the contrary, the share of countries that recorded an increasing number of convictions went down from 21% to 13% in the same period. Currently, 41% of countries have not had any convictions or have recorded less than 10 convictions between 2010–2012, even though these countries have legislation criminalising trafficking in persons. In the period from 2007–2010, 39% and in 2003–2007, 36% reported none or less than 10 convictions.11 On the other hand, 16% of countries reported more than 50 convictions from 2010–2012. This number was 18% in 2007–2010.12

In order to study regional conviction capacities, it is useful to compare convictions with the population size, since in very populous countries the number of convicted offenders tends to be higher. In Europe and Central Asia, the ratio of trafficking in persons convictions per 100,000 population is around 0.3 which is higher than in other regions where this ratio remains around 0.1.13 Comparing conviction rates with other crimes emphasises the low rates in trafficking in persons cases. For example, the average number of persons convicted for completed intentional homicides per 100,000 population in Europe in 2011 was 1.2, for assault (bodily injury) it was 74, for rape, it was 1.5. Among crimes connected to transnational organised crime, the number of persons convicted for money laundering per 100,000 population in Europe in 2011 was 0.7, for corruption it was 1.9 and for drug trafficking it was 21.14 These European figures show that trafficking in persons convictions seem to be very low even when compared with other serious crimes such as homicide or similarly hidden crimes such as rape.

There could be several reasons for the low number of convictions. First, it could be argued that the low number of convictions reflects a low level of instances of crime. Indeed, comparing the number of convictions to the number of detected victims demonstrates that often countries that report no or few convictions also identify very few victims. However, there are indications that often low conviction levels do not reflect the actual domestic human trafficking scenario. In this regard, around one-third of countries with no or few convictions identify significant numbers of victims.15 This shows that in many countries, the identification of victims does not lead to increased convictions and the conviction numbers do not reflect the trafficking in persons situation in these countries. As a result, it can be determined that, in many countries, low convictions of traffickers do not correlate to actual incidences of the offence; particularly, since trafficking in persons is often very hidden.

A second reason for low levels of convictions is the previously mentioned hidden nature of trafficking in persons. Human trafficking is largely a crime which does not easily come to the attention of the police, border control officers, health authorities, labour inspectors, embassy personnel, service providers or other persons who potentially could come into contact with human trafficking. Victims can be reluctant to report their traffickers due to control, intimidation, threats of violence and fear of being punished and deported to their origin country. Victim self-identification is difficult because of the complex nature of human trafficking. In some cases, trafficking victims may see little benefit in dealing with authorities and service providers that may infringe their human rights or even harm them.16 Even when victims are identified, they might be reluctant to cooperate with criminal justice authorities because of lack of trust, fear of being deported or prosecuted for related criminal activity, fear of being stigmatised, or for other reasons.

For several years, trafficking in women for sexual exploitation dominated the discussions on human trafficking so that trafficking for other forms of exploitation such as forced labour, begging, petty crime, organ removal and child soldiers received limited attention. This was also reflected in the identification of cases.17 However, the situation has changed in recent years. While in 2006, 21% of detected victims were trafficked for other purposes than sexual exploitation,18 in 2011, the share was 47%.19

In addition, authorities often have difficulties identifying perpetrators, particularly without the cooperation of victims, since proactive investigations relying on methods other than victim testimonies are seldom used.20 Therefore, the crime that is not seen cannot be prosecuted. The hidden nature of human trafficking makes an accurate estimate of the number of victims very challenging and when this is not known, it is very difficult to assess the level of convictions when compared to the estimated severity of trafficking.

However, some empirical studies have shed light on the prevalence of trafficking in persons. Based on his study on trafficking of migrant workers in San Diego county, Sheldon Zhang21 estimates that there could be as many as 2.472 million trafficking victims among undocumented Mexican migrants in the United States of America. Another study on trafficking in persons in Ukraine based on three different surveys concludes that in the three-to-five-year period under review, 22,000 to at least 36,000 Ukrainian citizens per year had been exploited abroad.22 At the same time, the data received by UNODC from Member States shows that the number of victims known to the authorities rarely reaches 1,000 per year in any country.23 These estimates from different countries clearly indicate that only a limited number of trafficking victims are identified and most human trafficking cases remain hidden. Based on these findings, we can safely assume that there are many trafficking in persons cases and traffickers that are not known to the authorities and thus cannot be prosecuted, all resulting in low levels of convictions. This is also related to the lack of capacity and prioritisation to address trafficking in persons crimes.

A third possible reason for low conviction rates is the limited capacity of national criminal justice practitioners to investigate and prosecute human trafficking cases. Courts can also suffer from lack of capacity to sanction traffickers properly. Limited capacity could be a result of many factors. Police officers and prosecutors may not be trained to identify trafficking in persons cases. Trafficking in persons crimes are often very complex offences that require intensive efforts to investigate and prosecute.24 This might lead to a situation where trafficking in persons cases are prosecuted and convicted to a lesser extent than other offences which are easier to investigate and require fewer resources. In some cases, the criminal justice system is reluctant to devote resources to investigate human trafficking cases which are not immediately visible to the citizens and which are not seen happening in the local community, leading citizens to believe that the crime does not concern them. This often means that there are no pressures on authorities to take action.25

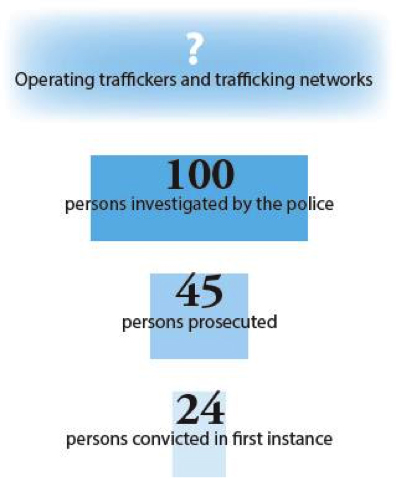

The capacity of the criminal justice system can also be evaluated by the percentage of suspected traffickers who are convicted.26 At the global level, out of 100 persons suspected of trafficking in persons, 45 suspects are prosecuted and 24 are convicted in the first instance. Of all those who are prosecuted for human trafficking, 55% are convicted.27

Figure 3. Probability of first-instance conviction for persons investigated for trafficking in persons

Source: UNODC 2014

There are, however, some regional differences in these attrition figures. In Western and Central Europe, around 30% of suspects and around 50% of those prosecuted are convicted in the first instance. Other regions in Asia, Americas and Africa present lower ratios.28 In order to review the efficiency of the criminal justice system in convicting suspected offenders of trafficking in persons cases, the figures can be compared with other crimes. Based on the UNODC Crime Trend Survey, which collects data globally on crimes in general, on average 60% of suspects are convicted.29 For homicide at the global level, for every 100 persons suspected, 44 are convicted.30 Compared to these figures, the efficiency of the criminal justice system to process trafficking in persons crimes and convict suspected offenders is relatively low, which might reflect the complex nature of human trafficking offences, the difficulty in collecting evidence needed for successful prosecution and/or lack of resources within the criminal justice systems.31 All this is naturally reflected in the low conviction numbers.

The fourth reason for low conviction figures is corruption. At present, there is only scattered evidence on the relationship between corruption and trafficking in persons showing the strong linkage between these two issues.32 A study in Brazil on corruption and trafficking in persons shows that 71% of all examined cases of domestic and international trafficking in and from Brazil had a linkage with corruption.33 The role of organised and structural corruption in human trafficking is presented in a study on Southern and Eastern European trafficking networks.34 Even ten years ago, experts and practitioners interviewed in the Czech Republic estimated that up to 30% of trafficking cases involved a hidden element of corruption.35 The role of corruption in trafficking for forced labour has been illustrated in a paper on the global supply chain.36 However, this linkage is not visible in the convictions since public officials and private actors are scarcely prosecuted or charged for their complicity in cases of human trafficking. A study in Finland demonstrates that legal practitioners and other authorities can benefit from trafficking-related activities; however, it is very difficult to prosecute these cases.37 The UNODC Human Trafficking Case Law Database, which contains more than 1,000 cases from nearly ninety countries, includes only nine cases where corruption is present.38 Corruption can have an impact on convictions in several ways. Police officers may purposefully ignore signs of trafficking or they may even enable it. They may warn criminals of raids or protect them after the raid. Government officials may attempt to draft legislation that hinders efficient responses and protects traffickers or blocks investigation, prosecution and conviction.39

Even when there are convictions related to trafficking in persons cases, the persons that are convicted might not be the heads of the criminal group or those who make the biggest profits. Based on an evaluation of cases included in the UNODC Human Trafficking Case Law Database involving an organised crime component, it could be concluded that most offenders were identified by the victims. Also, other research shows that there is a heavy dependency on victim testimonies when prosecuting trafficking in persons crimes, some prosecutors even refuse to go to trial without the victim’s testimony.40 This could lead to a situation where only those known to the victim, particularly recruiters, are prosecuted and convicted. The analysis of the data on assisted victims show that half of the recruiters are known to the victims as friends, relatives, business contacts or other acquaintances.41 Emphasising victims’ testimonies in the investigation and prosecution of trafficking crimes can result in the non-identification of members of the organised criminal groups, particularly the heads of these groups, who, at the end of the day, will be able to continue their criminal associations and activities. The endurance of the trafficking of Nigerian victims by Nigerian criminal groups to Europe for sexual exploitation illustrates this situation.

Nigerian organised criminal networks, which are structured around a highly hierarchical system, are mainly behind the trafficking of Nigerian victims.42 However, Nigerian organised crime groups do not always directly engage in the recruitment and exploitation of victims, but rather tax and control the activities within a certain territory.43 In this case, victims might not ever come into contact with the higher levels of management of the criminal organisation, and therefore would be unable to identify them or present evidence of their involvement. Another reason for low conviction rates of Nigerian offenders may be related to the closed structure of the trafficking network which is rigidly hierarchical and self-contained and in which victims are controlled both physically and mentally through a ritualistic practice.44 This often means that victims are very reluctant to reveal their experiences to outsiders and to testify against their traffickers. Since securing a conviction in many countries is highly dependent on victim testimony, Nigerian traffickers are difficult to prosecute. Criminal justice statistics in Europe support this theory, as among all non-European suspects, Nigerian traffickers made up the largest group between 2010–201245, but the conviction rates were only around 3% of the total number. At the same time, 10% of the total number of detected victims were from Nigeria.46

The percentage of women offenders convicted for trafficking in persons is globally around 30%. The share is higher than in other crimes where around 10–15% of convicted offenders are women.47 The share of female offenders is particularly high, above 50% in some countries of Eastern Europe and Central Asia and above 70% in the Southern Caucasus.48 One possible reason for such high figures is the focus on prosecuting recruiters, who are often women, and who in some cases might be forced to recruit victims, thereby becoming themselves victims of trafficking.49 A study on trafficking in persons in Finland involving mainly women victims trafficked from former Soviet Union countries shows that female traffickers are involved in the recruitment of other women, organising practical matters and coaching newly recruited women. Some female victims who were in a situation of debt bondage were actually forced to recruit other women in order to pay back their debts.50 Another study on trafficking networks operating in Italy in the late 1990s showed that female members of the criminal organisation were often used for activities most visible to victims such as recruitment, collecting money from clients, controlling victims and escorting them.51 It seems that the high share of convicted women may actually not reflect the exceptionally high participation of women in human trafficking crimes but rather the strategic placement of women by organised crime groups in more public realms of activity.

Since 2003, when the Trafficking Protocol entered into force, there has been a clear increase in the criminalisation of trafficking in persons, at least when measured by the number of countries with a specific offence against trafficking in persons. However, successful criminalisation requires more than the adoption of a legislation. The implementation and enforcement of the legislation has been weak in many countries and the number of convictions continues to be very low. The situation has not improved since 2003 even though increasing amounts of countries have more comprehensive legislation, as required by the Protocol. The reasons for the lack of success in the criminal justice response are probably related to the complicated and hidden nature of trafficking in persons which makes the crime difficult to address with current legislation and prosecution efforts. Investigation is time consuming and many countries do not have the resources for successful prosecutions. And those who do have many competing priorities in their domestic anti-crime agendas. A proper criminal justice response would require a focused effort to find the offenders and victims, combined with resources which would make the specialisation possible. This would hopefully lead to real criminalisation, sanctioning in particular those criminals who profit most from the exploitation of others. Without the successful implementation of legislation, trafficking in persons will remain only partially criminalised.

Kristiina Kangaspunta is heading the preparation of the ‘Global Report on Trafficking in Persons’ at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in Vienna, Austria. The biannual Global Report has been published in 2012 and 2014 presenting the global and regional human trafficking trends and patterns. Previously, she was the Deputy Director of the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI) leading the Research Programme of the Institute in Turin, Italy. Before UNICRI, she worked with UNODC as the Chief of the Anti-Human Trafficking Unit. She moved to UNODC from the Ministry of Justice of Finland where she worked at the European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI).

1 Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, supplementing the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, retrieved 5 March 2015, http://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNTOC/Publications/TOC%20Convention/TOCebook-e.pdf

2 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), ‘Legislative Guides for the Implementation of the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and the Protocols thereto’, UN, New York, 2004, p. 267.

3 ‘Trafficking in persons’ shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.

4 A T Gallagher, The International Law of Human Trafficking, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2010; R Piotrowicz, ‘The UNHCR’s Guidelines on Human Trafficking’, International Journal of Refugee Law, vol. 20, issue 2, 2008, pp. 242–252; L Shoaps, ‘Room For Improvement: Palermo Protocol and the Trafficking Victims Protection Act’, Lewis & Clark Law Review, vol. 17, no. 3, 2013; J Todres, ‘Widening Our Lens: Incorporating Essential Perspectives in the Fight Against Human Trafficking’, Michigan Journal of International Law, vol. 33, Georgia State University College of Law, Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2011–29, 2011, pp. 53–76 , retrieved 5 March 2015, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1958164##

5 Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW), ‘Collateral Damage: The Impact of Anti-Trafficking Measures on Human Rights around the World’, GAATW, 2007.

6 Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings, retrieved 5 March 2015, http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/Html/197.htmv

7 As of August 2014.

8 UNODC, ‘Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2014’, United Nations publication, 2014, pp. 51–52.

9 UNODC 2014.

10 M McAdam, ‘Who’s Who at the Border? A rights-based approach to identifying human trafficking at international borders’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 2, 2013, pp. 33–49; S Plambech, ‘Between “Victims” and “Criminals”: Rescue, Deportation, and Everyday Violence Among Nigerian Migrants’, Social Politics, vol. 21, no. 3, 2014.

11 UNODC, ‘Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2012’, United Nations publications, 2012; UNODC/UN Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking (UN.GIFT), ‘Global Report on Trafficking in Person 2009’, UNODC, 2009, p. 40.

12 UNODC 2014, p.13.

13 UNODC 2014, p. 54.

14 M Aebi, G Akdeniz, G Barclay, C Campistol, S Caneppele, B Gruszczyńska, S Harrendorf, M Heiskanen, V Hysi, J Jehle, A Jokinen, A Kensey, M Killias, C Lewis, E Savona, P Smith, R Þórisdóttir, ‘European Sourcebook of Crime and Criminal Justice Statistics 2014’, Fifth edition, European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI) Publication Series No. 80, Helsinki, 2014.

15 UNODC 2014, p. 54.

16 GAATW.

17 K Kangaspunta, ‘Collecting Data on Human Trafficking: Availability, Reliability and Comparability of Trafficking Data’ in E Savona and S Stefanizzi, Measuring Human Trafficking, Complexities and Pitfalls, Springer, New York, 2007.

18 UNODC/UN.GIFT, p. 50.

19 UNODC 2014, p. 33.

20 A Farrell, ‘Improving Law Enforcement Identification and Response to Human Trafficking’ in J Winterdyk, B Perrin, P Reichel (eds.), Human Trafficking: Exploring the International Nature, Concerns, and Complexities, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2012; A T Gallagher & P Holmes, ‘Developing an Effective Criminal Justice Response to Human Trafficking. Lessons From the Front Line’, International Criminal Justice Review, vol. 18, no. 3, 2008, pp. 318—343.

21 S Zhang, ‘Trafficking of Migrant Laborers in San Diego County: Looking for a hidden population’, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA, 2012.

22 D Ball & R Hampton, Estimating the Extent of Human Trafficking from Ukraine, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2009, retrieved 28 January 2015, http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/humtraffconf/25/

23 UNODC 2014.

24 A Herz, ‘Human Trafficking and Police Investigations’ in J Winterdyk, B Perrin, P Reichel (eds.), Human Trafficking: Exploring the International Nature, Concerns, and Complexities, CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2012.

25 Farrell, p.196.

26 This loss of cases or filtering out of cases during the criminal justice process is called attrition (see Aebi et al., 2014, p. 154).

27 UNODC 2014, p. 55.

28 UNODC 2014.

29 S Harrendorf, M Heiskanen, S Malby (eds.), ‘International Statistics on Crime and Justice’, HEUNI Publication Series 64, 2010, p. 92.

30 UNODC, ‘Global Study on Homicide 2013’, United Nations publications, 2014, p. 93.

31 M Wade, ‘Prosecution of Trafficking in Human Beings Cases’ in J Winterdyk, B Perrin, P L Reichel (eds.), Human Trafficking: Exploring the International Nature, Concerns, and Complexities, CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2012.

32 L Holmes, ‘Human Trafficking and Corruption: Triple Victimisation?’ in Cornelius Friesendorf (ed.), Strategies Against Human Trafficking: The Role of the Security Sector, National Defence Academy and Austrian Ministry of Defence and Sports, DCAF, 2009, pp. 87–99.

33 A Cirineo & S Studnicka, ‘Corruption and Human Trafficking in Brazil: Findings from a Multi-Modal Approach’, European Journal of Criminology, vol. 7, no. 1, 2010, pp. 29–43.

34 J Leman & S Janssens, ‘The Albanian and Post-Soviet Business of Trafficking Women for Prostitution. Structural Development and Financial Modus Operandi’, European Journal of Criminology, vol. 5 (4), 2008, pp. 433–451.

35 I Trávníčková, Trafficking in Women: The Czech Republic Perspective, Institute for Criminology and Social Prevention (IKSP), Prague, 2004, p. 10.

36 Verité, ‘Corruption & Labor Trafficking in Global Supply Chains’, 2013, retrieved 28 January 2015, http://www.verite.org/sites/default/files/images/WhitePaperCorruptionLaborTrafficking.pdf

37 M Viuhko & A Jokinen, Human Trafficking and Organised Crime. Trafficking for sexual exploitation and organised procuring in Finland, Publication Series No. 62, HEUNI, 2009.

38 UNODC Case Law Database, retrieved 28 January 2015, http://www.unodc.org/cld/index.jspx

39 K Kangaspunta, ‘Trafficking in persons and its links to corruption’, presentation at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Pathfinder Dialogue on Combating Corruption and Illicit Trade across the Asia-Pacific Region: A Shared Partnership for Protecting National Assets, Human Capital and Natural Resources, Bangkok, Thailand, 2013.

40 A Farrell, J McDevitt, R Pfeffer, S Fahy, C Owens, M Dank & W Adams ‘Identifying Challenges to Improve the FRA (2009) Child Trafficking in the European Union—Challenges, perspectives and good practices’, European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2012, p. 8.

41 IOM, ‘IOM Counter Trafficking Database. Counter Trafficking (CTM)—Return and Assistance’, IOM, 2009, unpublished material.

42 Federal Centre for the Analysis of Migration Flows, the Protection of Fundamental Rights of Foreigners and the Fight against Human Trafficking, ‘Annual Report on human trafficking 2013. Building Bridges’, Brussels, Belgium, 2014; UN Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNCRI), ‘Trafficking of Nigerian Girls in Italy’, UNICRI, Turin, 2010; J Carling, ‘Migration, Human Smuggling and Trafficking from Nigeria to Europe’, IOM, 2006; UNODC 2014.

43 UNODC 2014, p. 57.

44 UNICRI; Federal Centre for the Analysis of Migration Flows, the Protection of Fundamental Rights of Foreigners and the Fight against Human Trafficking.

45 European Union, ‘Trafficking in Human Beings’, 2014 edition, Eurostat Statistical working Papers, 2014.

46 Based on the information UNODC has received from Member States.

47 UNODC 2014, p. 27.

48 UNODC 2014.

49 Information received from local experts.

50 M Viuhko & A Jokinen, p. 80.

51 E Ciconte, The Trafficking Flows and Routes of Eastern Europe, WEST-Women East Smuggling Trafficking, Ravenna, 2005.