ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

Amalia L. Cabezas

This article challenges the notion that the organised sex worker movement originated in the Global North. Beginning in Havana, Cuba at the end of the nineteenth century, sex workers in the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region have been organising for recognition and labour rights. This article focuses on some of the movement’s advances, such as the election of a sex worker to public office in the Dominican Republic, the system where Nicaraguan sex workers act as court-appointed judicial facilitators, the networks of sex worker organisations throughout the region, and cutting-edge media strategies used to claim social and labour rights. Sex workers are using novel strategies designed to disrupt the hegemonic social order; contest the inequalities, discrimination, and injustices experienced by women in the sex trade; provoke critical reflection; and raise the visibility of sex work advocacy. New challenges to the movement include the abolitionist movement, the conflation of all forms of sex work with human trafficking, and practices that seek to ‘rescue’ consenting adults from the sex trade.

Keywords: sex work, sex worker movement, sex worker organisations, media, Latin America and the Caribbean

Please cite this article as: A L Cabezas, ‘Latin American and Caribbean Sex Workers: Gains and challenges in the movement’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 12, 2019, pp. 37-56, www.antitraffickingreview.org.

In February 2018, a Dominican newspaper reported the arrest of street-based sex workers and the response of Congresswoman Jacqueline Montero:

SANTO DOMINGO, Dominican Republic. The deputy of the PRM (Partido Revolucionario Moderno—Modern Revolutionary Party), for San Cristóbal, Jacqueline Montero, denounced that last weekend’s capture of dozens of female sex workers who worked in the surroundings of the Basílica Nuestra Señora de Altagracia (Our Lady of Altagracia) in Higüey, is another example of the discrimination and violation of rights that this sector experiences. ‘In the Dominican Republic, there is no law that prohibits sex work, therefore, that detention was illegal’, she said.[1]

That a congresswoman would be involved in this type of exchange in such a deeply conservative Catholic nation is surprising. She spoke as an elected official of the PRM, a social democratic political party in the Dominican Republic. Montero, who is regularly interviewed by various media outlets, started her political career in 2010 as a city council member in Haina, a municipality outside the capital of Santo Domingo. In 2016, she was elected to the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of the Dominican Congress. In the same newspaper interview, Montero added that, ‘it is natural for sex workers to choose this area to offer their services, because it is a well-travelled area’. Montero’s intimate knowledge of the public spaces of sex work, and of the applicable laws regulating the sex trade, emerges from her background as a former sex worker and as a leader in an organisation by and for sex workers. Indeed, newspaper accounts reveal that Montero is outspoken about her support for sex worker rights, and her background as a former sex worker positions her as an expert to openly advocate for the cessation of harassment, criminalisation, stigma, and violence targeting sex workers. In fact, Montero routinely demands that the state create jobs for single mothers. In the interview, she stated that ‘the majority of the compañeras (comrades) that engage in sex work are single mothers who must support their children alone and face difficulties getting a job because of the discrimination they experience on a day-to-day basis. The state must guarantee their rights instead of mistreating them’.[2]

In Latin America and the Caribbean, there is a long tradition of sex workers advocating for social and labour rights. Montero is just the latest sex worker to enter the political arena to publicly address issues impacting those involved in the sex trade. High-profile sex workers, such as Claudia Colimoro of Mexico City and Gabriela Leite of Brazil, have openly challenged juridical structures and social mores and also ran for elected office in their respective countries.[3] While some accounts attribute the political organisation of sex workers to the influence of the North American and European movements—referred to as the ‘first wave’ of sex worker organising[4]—Latin American and Caribbean sex workers have a long history of their own.[5]

This article documents the emergence of the sex worker movement in Latin America and the Caribbean in the nineteenth century, a history challenging the literature that suggests that sex workers first organised in the Global North in the 1970s.[6] While the sex worker movement in the Global North has received the majority of English-language scholarly attention, I turn to Latin America and the Caribbean, an under-researched region in sex worker studies, to indicate the historical persistence of sex workers organising for social justice and change.

I begin with a discussion of the prostitute collective formed in Havana, Cuba, at the end of the nineteenth century, and then explore sex workers’ oppositional cultures of resistance in Mexico and Ecuador during the twentieth century. I also examine the network of sex worker organisations, linked to global advocacy organisations, which currently operate in the majority of countries of Latin America and the Caribbean. I then explore some of the cutting-edge media strategies and other initiatives crafted by sex workers in Spanish-speaking countries. The examples chosen indicate how sex workers challenge the hegemonic gender, sex, and labour regimes and present alternative visions. I argue that the current contiguous networks, pioneering juridical interventions, and sex worker radical media and other practices are solidifying the foundation of a transhemispheric movement. It is important to examine the advances of and challenges faced by this movement in order to understand its lessons for other parts of the world.

The examples of sex worker advocacy I have chosen to highlight in this article—radical uses of the media, organising, and juridical intervention—are not exhaustive but rather illustrative. They were selected because they represent novel strategies designed to disrupt the hegemonic social order, contest the inequalities, discrimination, and injustices experienced by cisgendered and trans women in the sex trade, provoke critical reflection, and raise the visibility of sex work advocacy.[7]

This article focuses on selected examples from Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. More research on organising efforts is needed, particularly ethnographies investigating the Dutch, French, and English-speaking countries in LAC. Likewise, more research on male sex workers and their incorporation into the movement is necessary. Finally, further analysis is required of the uses of social media for organising the diverse populations of sex workers in the region.

Most accounts of the origins of the sex worker movement reference Global North precursors, such as the occupation of the Saint-Nizier Church by prostitutes in Lyon, France, in 1975, the establishment of the English Collective of Prostitutes in London during the same year, and the creation of Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics (COYOTE) in San Francisco in 1973. In the Americas, however, the conception of prostitution as a form of labour—and not sin, vice, or the depravity of ‘fallen women’—was first articulated by a Caribbean collective of prostitutes who sought to organise politically to demand their rights as workers. Indeed, sex workers in Latin America have a long history of organising, publicly challenging and resisting unjust regulations and policies.

An often-ignored forerunner of the global movement for sex worker rights began in Cuba. In the late nineteenth century, during a period of increased migration from European countries and the circulation of women in Latin America and the Caribbean, women worked in the brothels of Havana, which had been a popular destination for sex since the beginning of the Spanish Conquest. As historians have uncovered, migrant women travelled from Europe, the United States, the Canary Islands, Mexico, Panama, Spain, and Venezuela to Havana to eke out a living in the red-light district. Some of the matrons, or madams, were well-to-do, having earned large sums of money in their youth.[8] They invested their savings and established entertainment venues that offered prostitution, gambling, and dancing. As brothel owners, they made a decent living, and began to exercise their economic power by challenging the corrupt practices of the Spanish colonial administration.

In 1888, a group of Havana sex workers founded a newspaper to voice their anti-government views and called for the establishment of a political party led by sex workers. Financed by wealthy sex workers and edited by a Spanish immigrant anarchist, Victorino Reineri Jimeno, the newspaper was a medium for protest, countering discriminatory laws and unethical officials in the colonial government.[9] La Cebolla: Periódico ilustrado, órgano oficial del partido de su nombre (The Onion: Illustrated Newspaper, Official Organ of the Party with the Same Name) was widely distributed throughout Havana and other Cuban provinces and openly advocated for the rights of prostitutes in cosmopolitan Havana. The name of the newspaper alluded to the formation of a sex worker political party. However, historians have not been able to uncover evidence of a political organisation attached to the journal.[10] The newspaper was envisioned as a publication for and by prostitutes. The newspaper advocated for changes to the Reglamento de Higiene Pública (Public Hygiene Regulation), an administrative system that, in part, sought to reduce the incidences of sexually transmitted infections by registering sex workers and forcing them to carry identity cards and submit to gynaecological examinations. This imported system of state regulation of sex work initially came from France and England, but was later adopted throughout the Americas.[11]

A series of articles published in La Cebolla in September 1888 ridiculed and protested government regulations imposed on brothel-based sex workers, including the high regulatory fees and mandatory medical check-ups. As historian María del Carmen Barcia Zequeira points out, sex workers defined themselves as a marginal and exploited class because they saw themselves as victims of continuous extortion at the hands of the authorities who sought to control their activities.[12] One unsigned letter stated:

The Mayor, who is so old and cranky that not even a fly dares to land on him, has decreed that we cannot exhibit ourselves in the doorways of our own establishments. […] Is this fair? What country prohibits a businessman from showing the public his merchandise? The ‘horizontals’ of this city pay more contributions to the state than necessary. Yet, even though we contribute more than any other sector to bolster the revenues of the state with the sweat of our […] brows, we are treated as if we were slaves, as if we were outlaws. In other words, we are considered citizens so as to meet our obligations but not to enjoy the rights of citizenship.[13]

The ‘horizontals’—the name used to denote sex workers in the paper—did not shy away from protesting the control of prostitutes’ lives by challenging an exploitative administrative system that was being paid for with all the regulations enacted over their bodies. Another article advocated for the formation of a professional guild of prostitutes that would back their demands and fight for the recognition of sexual services as a system of labour. Using humour and candour, sex workers publicly exposed their exploitation in print media, inspiring the creation of a new identity for prostitutes as labouring women.

Both the rebellious and demanding spectacle of so-called ‘public women’ who had no shame in identifying as prostitutes and the publication of La Cebolla were acts of defiance against a Spanish colonial administration that was already under attack by the Cuban independence movement. Government officials retaliated, banning the newspaper and incarcerating the editor. Nevertheless, the short-lived campaign highlighted the fact that sex workers were no longer politically powerless, invisible, and easily vilified. Thus, in Havana, at the end of the nineteenth century, women who made a living in the sex industry envisioned the formation of a political party that would demand their rights. This important intervention was the genesis of the current transnational social movement of sex working women in Latin America and the Caribbean. As I detail below, these organisations have been able to realise some of the achievements imagined by the women of La Cebolla.

The case of Mexico offers an example of sex workers refusing to align themselves with labour politics. In the 1920s and 1930s, in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution, during a period of rapid urbanisation and nation-building, sex workers saw the manifestation of political organising as an affront to their identities as decent people. In Mexico City, as historian Katherine Bliss’ scholarship documents, women working in the sex trade insisted that they were part of communities and households for which they bore responsibility. Seeking to be regarded as gente decente (decent, honourable people), they affirmed their identities as providers for their families and, by extension, the nation. When radical labour unions sought to unionise them to improve working conditions in brothels and cabarets, they manifested their resolve by refusing to be controlled by labour organisers. Instead, they claimed a more flexible political subjectivity that did not inscribe them into permanent states of stigma and shame. Defying the discourse of ‘vice’ or even ‘individual desperation’, they emphasised their role and identity as ‘conscientious parents and providers’.[14] For them, sex work was an income-generating activity they undertook on a temporary basis to support their families, and thus was tied to reproductive labour. By proclaiming the right to live as gente decente, they challenged the structural conditions of gendered poverty that relegated them to the margins of society and the mores that pinned them as deviant women within hegemonic meanings of prostitution. While they did not want to be aligned with labour rights and unionisation, they nevertheless spoke out in opposition to the injustices they faced.

Paradoxically, sex workers in Mexico City also rejected the Department of Public Health’s efforts to abolish sex trade businesses, such as cabarets, and to deregulate the red-light district. Instead, as Bliss establishes, ‘while many women acknowledged that their work was undesirable, they insisted that they engaged in sex work because they were honourable daughters and mothers supporting deserving family members’. Sex workers also appealed to revolutionary fervour by maintaining that their work was in service of the nation and its families. They proclaimed that they ‘“threw themselves into the street” and participated in a profession that put them at risk of abuse, violence, and disease to protect their children, Mexico’s future workers and leaders’.[15] In effect, sex workers challenged their marginalisation, thus affirming their right to work and their normative social identity, while linking the domains of sexuality, social reproduction, nationhood, and economy.

In the 1980s, sex workers established grassroots organisations in various parts of Latin America. Women in Uruguay’s sex trade were one of the first groups to organise in 1986. Shortly thereafter, Uruguayan sex workers obtained social security and health benefits for their occupation. In 1987, two Brazilian sex workers, Gabriela Leite and Lourdes Barreto, held Brazil’s first national conference for sex workers.[16] By 2007, sex workers from Davida, a Brazilian organisation that champions the rights of prostitutes, had launched the fashion line Daspu in Rio de Janeiro, which became the first fashion house created and managed by sex workers.[17] Currently, there are several sex worker organisations throughout Brazil, including Rede Brasileira de Prostitutas (National Network of Prostitutes) and Federação Nacional das Trabalhadoras do Sexo (National Federation of Sex Workers).[18]

In the early 1980s, one of the first sex worker collectives was organised in El Oro province in Ecuador. On 22 June 1982, 300 brothel-based women united to form La Asociación Femenina de Trabajadoras Sexuales Autónomas (Association of Independent Female Sex Workers) and, in 1988, they went on strike in an effort to negotiate better treatment from brothel owners.[19] Their success inspired the formation of other sex worker collectives throughout the country. By 1993, when sex workers convened Ecuador’s first national conference, there were eleven community organisations of sex workers calling for improvements in working conditions, health, and security. According to Lourdes Torres, the president of the brothel-based sex workers’ organisation Asociación para la Defensa de la Mujer (Association for the Defence of Women), Ecuador has at least one sex worker collective in every province of the country.[20]

Ironically, during the 1980s, the HIV/AIDS pandemic made governments and supra-national health associations pay attention to the role that sex workers could play in preventing and eradicating the virus. According to Mzilikazi Koné’s research, the entry point into work with sex workers was around HIV prevention and empowerment. Sexual health was primary, and empowerment and organising came through that initial sexual health-centric model.[21] Sex workers, however, continued to be targeted by state interventionist efforts to eliminate venereal diseases, but these problematic practices drew sex workers together and facilitated further organising.[22] Regional gatherings, for example, resulted in the formation of various transnational networks. Currently, these networks are linked to similar actions in more developed countries and represent Latin America and the Caribbean’s entry into the global stage of the struggle for sex workers’ rights.

The transnational associations began in Costa Rica in 1997, when the Red de Mujeres Trabajadoras Sexuales de Latinoamérica y el Caribe (Network of Women Sex Workers in Latin America and the Caribbean—RedTraSex) was born as a transnational non-government association of sex worker groups in the region and has since built political influence.[23] RedTraSex is headquartered in Argentina, linking associations in fourteen countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, and Peru. Sociologist Jorgelina Loza explains that ‘the central claim of the women that make up RedTraSex is their demand to be recognised by the nation states to which they belong as subjects of rights, that is, as workers who have the right to access decent working conditions and social benefits: housing, health, retirement and pensions’.[24] Through a feminist, rights-based approach, RedTraSex coordinates programmes to unite sex workers around issues that impact their lives, including advocating for improved access to medical care free of discrimination, anti-violence initiatives, safe working environments, sexual health, and mobilising in opposition to human trafficking.

RedTraSex has enhanced visibility, influence, and activism through a number of accomplishments. This is not an exhaustive list, but I highlight a few significant gains facilitated by cross-national collaboration. First, the connections produced by transnational ties within the region and internationally have fortified activists’ image and legitimacy and created a platform to denounce the normalised violence that sex workers routinely face. Samantha Carrillo, of the Organización Mujeres En Superación (Organisation for Women’s Empowerment), reflected on their increasing political clout in Guatemala: ‘we were a crazy trio thinking that someday we were going to have a house and that someday we were going to sit down with the officials to talk about us as sex workers’. She went on to add:

Every year, every day, every step we take, we are no longer a crazy trio. Today we are thirty-five female sex workers [who] day-to-day, work in preparation, arranging with the directors of health centres, talking with members of congress, with ministers, and talking about how we want to change not only the working conditions but also the conditions in health and also our rights.[25]

Consuelo Raymundo, affiliated with Movimiento De Mujeres Orquideas del Mar (Women’s Movement Orchids of the Sea), in El Salvador, echoed this sentiment when she stated, ‘RedTraSex provides us greater visibility with government institutions. If we are alone nothing happens but when we are united in so many countries people tends [sic] to take us seriously’.[26] This level of respect would be difficult to achieve without the power and strength of a regional network.

Second, the organisations prioritise a model of governance that puts sex workers in charge of the direction of the movement. Thus, the leadership is comprised primarily of sex workers, even if they lack formal schooling.[27] Furthermore, cross-cultural and cross-national approaches have injected new tactics into the national landscape. As RedTraSex member Ángela Villón, representative of Peruvian sex worker organisation Miluska Vida y Dignidad (Miluska Life and Dignity), reported, ‘to see how things work in other countries allows [us] to find models that we can adapt to our own reality’.[28] Even though members are confronted with language barriers, cultural and racial differences, technological difficulties in communication, and financial uncertainties, their advocacy strengths are shaping public and political spaces for people in the sex industry at the national and regional level.

RedTraSex engages in diverse forms and areas of advocacy designed to empower sex workers. These include communication campaigns, the development of awareness campaigns aimed at different national actors, and the formation and strengthening of community-based sex worker organisations. It also conducts research and develops position papers on key issues, such as sexual and reproductive rights, violence, labour rights, and the distinction between sex work and human trafficking.[29]

A second regional network, Plataforma Latinoamericana de Personas que Ejercen el Trabajo Sexual (Latin American Platform of People Who Exercise Sex Work—PLAPERTS), is headquartered in Ecuador. Organisations from Brazil, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru started this regional platform of the Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP) in 2014. As in the case of RedTraSex, the platform’s member organisations call for the recognition of sex work as a legitimate occupation, struggle to improve the working conditions of sex workers, and inform their members about their rights. There are also smaller regional organisations. In the Caribbean, the regional Caribbean Sex Worker Coalition (CSWC), formed in 2011, brings together sex workers from English-, Dutch-, and Spanish-speaking countries. CSWC is comprised of groups based in Antigua, Belize, Grenada, the Dominican Republic, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago. It includes, among others, the Caribbean Regional Trans in Action (CRTA), an organisation supporting trans women in sex work. The majority of the member alliances work principally with cis-gendered and transgender women involved in sex work regardless of their sexual identity, though some also include male sex workers.

Both PLAPERTS and RedTraSex have created new paradigms for women working in the sex industry. These paradigms combine communality, collaboration, and new social and political subject positions. As workers, feminists, and citizens worthy of human rights protections, they are committed to mutual support and respect. The different collectives are also dedicated to the empowerment of sex workers and achieving legislative change in their respective countries, as detailed below.

The flourishing network of sex worker organisations that emerged since the 1980s also actively participates in civil society, primarily through the creation of non-governmental organisations and entry into the political sphere. Jacqueline Montero, for instance, in addition to serving as an elected representative in the Dominican Congress, also serves as the president of the sex worker organisation Movimiento de Mujeres Unidas (Movement of United Women—MODEMU), a non-governmental organisation started by the Centro de Orientación e Investigación Integral (Integral Orientation and Research Center—COIN). COIN is a community-based organisation in Santo Domingo that supports sex workers as part of their agenda to provide safer sex education to vulnerable populations.[30] Founded in 1996, MODEMU was the only sex worker organisation in the country until 2016, when former members of MODEMU started a new group headed by Miriam Altagracia Gonzalez Gómez, a founding member of MODEMU. The Organización de Trabajadoras Sexuales (Organisation of Sex Workers—OTRASEX) works closely with RedTraSex, and has recently conducted research on police violence aimed at sex workers and held educational workshops with members of the armed forces. The existence of two sex worker organisations in such a small country is testament to the self-determination and heterogeneity of perspectives in the movement for social, labour, and political rights.

The official acceptance of sex work as a type of labour is one of the central principles of the sex worker rights movement. In addition to the advocacy efforts of the networks in Latin America and the Caribbean, in individual countries, women engaged in sex work are fighting for alternative visions of justice. In Nicaragua, the sex worker organisation Girasoles de Nicaragua (Sunflowers of Nicaragua) has recently made headway in the struggle for awareness of their rights as precarious labourers, and positioned sex workers as an integral part of the justice system.

Founded in November 2007, Girasoles de Nicaragua currently boasts more than 2,300 members. The collective, in conjunction with the country’s Supreme Court, created the first programme of sex worker judicial mediators. This conflict resolution model reduces caseloads in the courts and enhances communication between the justice system and sex workers. Nicaragua is the first country in the world that has trained sex workers to resolve conflicts within their jurisdiction; officially trained and accredited by the Supreme Court of Justice, eighteen sex workers assist the Administration of Justice as judicial facilitators, resolving conflicts related to sex work, and preventing and decreasing violence. In an interview, the President of the Supreme Court of Justice, Alba Luz Ramos, stated, ‘it is the best way to do it, because they [sex workers] sometimes feel discriminated against by the rest of the community.’[31] As an example of the programme’s efficacy, María Elena Dávila, president of Girasoles, said in an interview that judicial facilitators were able to assist a 23-year-old co-worker who was stabbed by a client. The client went to jail, and the judicial facilitators monitored the process ‘to ensure that the police and forensic medicine do their job’.[32] She went on to explain how the incorporation of sex worker advocates is a crucial step in the process, in that it helps to ensure that sex workers are not victimised by the police and the justice system.

In an interview in 2015, Dávila was asked how she felt about Nicaraguan sex workers participating as judicial facilitators. She replied:

We already feel recognised, but we do not have a document that says as of this day sex workers enjoy the same rights as the workers’ union. We will achieve it, because that is the challenge, but I cannot say whether today or tomorrow... Then we would be happier than we are now. That would be the final point, but each right [we gain] is leading to demand another.[33]

Girasoles achieved this goal in 2017, when Nicaragua recognised sex work as a form of labour. It became the third country in Latin America, after Colombia and Guatemala, to have a sex workers’ union acknowledged by the Ministry of Labour. Currently, Girasoles is attached to the Confederación de Trabajadores por Cuenta Propia (Confederation of Self-Employed Workers), a union representing people who work in the informal economy, selling all kinds of inexpensive goods and services.

Garnering further media attention, the program of judicial facilitators was featured in a 2017 documentary film, Girasoles de Nicaragua, which premiered at international film festivals. Created by a feminist filmmaker, Girasoles de Nicaragua follows Nicaraguan sex workers as they champion for fair treatment of sex workers and the inclusion of their voices in community-based conflict resolution.[34]

The victories secured by sex worker activists working together for social acceptance and political visibility have been hard-won. The struggle to change the stigma against women living in poverty, and working-class single mothers, is compounded by the sexualisation of their labour. As the cases of Argentina and Columbia, detailed below, illustrate, public interventions and cultural resistance can challenge stigmatising moralities and humanise sexual labourers.

In 1994, a group of women engaged in Argentina’s sex trade came together in the city of Buenos Aires with the objectives of organising to oppose police violence and arbitrary arrests and to fight for basic rights.[35] The Asociación de Mujeres Meretrices de Argentina (Association of Women Sex Workers of Argentina—AMMAR) was born in 1995 and has been at the forefront of efforts to organise women engaged in the sale of sexual services with a focus on advocacy and mutual help. AMMAR is integrated into the trade union umbrella confederation, the Central de Trabajadores Argentinos (Argentine Workers’ Central Union), which represents the interests of informal sector workers.[36] In Argentina, the sale of sex is not criminalised at the federal level, but brothels and third parties that profit from sex work and advertisements are outlawed. The regulations date back to 1937, when they were first instituted to combat venereal diseases.[37]

Recognised as a non-profit organisation, AMMAR has influenced public policy and built political alliances with other workers. In 2003, 2008, and 2010, AMMAR succeeded in having local laws repealed that criminalised sex workers and empowered police to arrest them and violate their rights. In 2018, they successfully fought for the repeal of a code in Buenos Aires that authorised fines and the arrest of sex workers, routinely applied to trans- and cis- women on the grounds of being ‘scandalous’.[38]

At the intersection of popular culture and radical media, and on the heels of La Cebolla, AMMAR has cleverly utilised public spaces to drive home a political message. Borrowing from Banksy’s famous street stencils, the organisation started an innovative campaign in 2013, by adorning walls on various street corners in Buenos Aires with mural paintings. Depicting women on one side and their children on the other, the campaign stressed that 86 per cent of Argentine sex workers are mothers, bringing attention to the fact that sex workers are women with familial connections and obligations, and are integrated into communities as mothers and breadwinners.[39] The murals not only facilitated neighbourhood discussions and awareness, but this labour rights campaign also received widespread media attention, even winning an international prize from a public relations and communications magazine.[40]

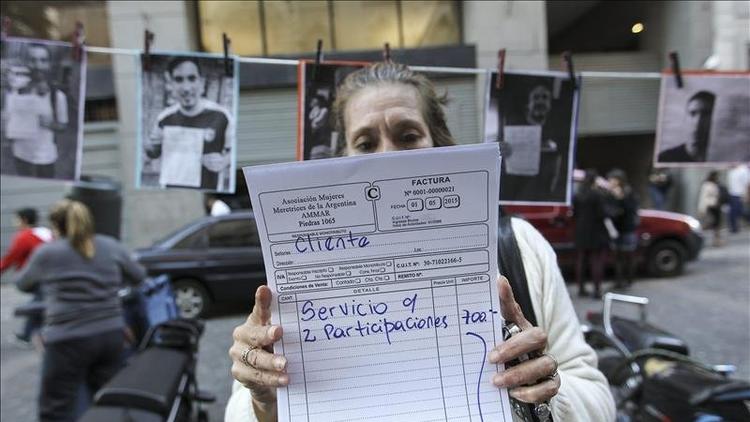

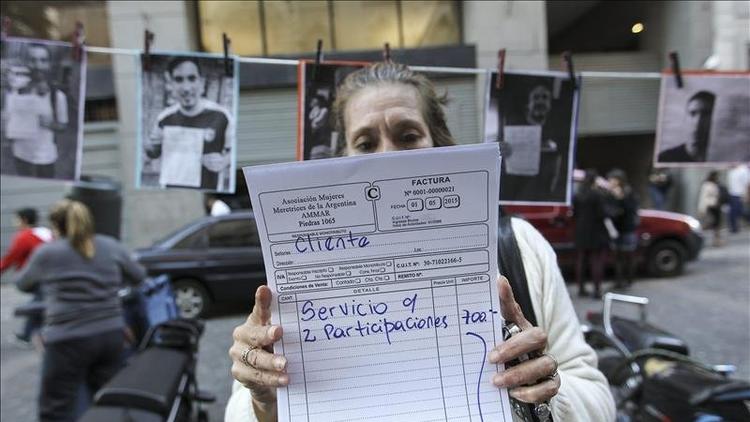

AMMAR produced another impactful intervention in the form of a public sphere performance in which activists randomly distributed fake invoices for sexual services rendered, complete with price details. The campaign also targeted journalists, opinion leaders, and politicians, among others.

The objective was to make evident that sexual services involve a financial transaction similar to other enterprises, with obligations and rights which, if decriminalised, would also have ramifications for public finances. Georgina Orellano, the general secretary of AMMAR, declared that their aim was to highlight the importance of autonomous sexual labour for adult women who voluntarily decide to engage in this work.[41] AMMAR’s ingenious initiative, designed to promote acceptance of sex workers and support for their rights, generated media attention and once more initiated public awareness and discussion.

In another part of Hispanic America, a group of mostly trans sex workers in Santa Fe, Colombia, near the capital of Bogotá, created a mural that later inspired a printed newspaper called La Esquina (The Corner) in 2018.

Staffed by trans sex workers, La Esquina is a media space where community members share information of community interest, such as how to avoid complications related to surgical procedures, how to get a job, how to make cheap meals, and how to take better care of their health.[42] Funded by non-profit organisations, La Esquina has a mural edition that is laminated and pasted to walls on street corners where sex workers congregate to wait for their clients. It also has a regular print edition that is distributed to brothels and other businesses in areas patronised by sex workers.

La Esquina addresses the interests, needs, and empowerment of a disadvantaged community that is doubly discriminated against for being trans and sex workers. At the outset, surveys were used to determine what community members wanted to see and read; politics received a ‘clear thumbs down, while residents said they really wanted to hear about security, health, and events.’[43] For staff members such as Marcela, a 56-year-old trans woman with limited literacy skills, La Esquina offers the opportunity to visually communicate stories. Conveying her disdain for mainstream media that exclude trans issues ‘because they only look for us to tell the morbid thing that woke them up’,[44] she uses photography to document stories for the newspaper. In commenting on her work, the Colombian newspaper Semana stated that, ‘Marcela thinks in frames, in all those stories that are walking through the streets of Santa Fe and that hide in exposed skin and tattoos.’[45] Without La Esquina, those stories would not be told. Likewise, the section created by staff member Lorena, called ‘Gourmet at 10 lucas’ (lucas is the slang word for pesos), features low-cost recipes, with the explicit goal of introducing trans sex workers to different foods. For, as Lorena specifies, she knows well that they can spend entire nights without eating anything. The various features included in the paper share a common thread: they are deeply committed to contesting and transforming the daily violence, social exclusion, and invisibility experienced by trans sex workers. Writing about La Esquina, the British newspaper The Guardian opined, ‘in a neighbourhood where violence and murder usually steal the headlines, La Esquina is making an impact in [a] gentler way’.[46]

By challenging transphobia, sharing mutual interests, and creating new venues for creative expression, La Esquina is a type of radical media that produces critical and transformative thinking in a marginal setting. It represents an invitation for the wider sex worker movement to think in terms of accessibility, diversity, and the creation of new literacies for its members.

Latin America and the Caribbean have a long history of sex worker organisations that have struggled for better working conditions free of institutional violence and oppression. The militancy and dedication of the sex worker movement in the region represents the continued demand for recognition—just as they did in the late nineteenth-century Havana. Instead of a corrupt colonial administration, they now face an equally powerful neo-colonial and neoliberal context that undermines their livelihoods and rights.

Ongoing issues for the Latin American and Caribbean sex worker movement include access to labour rights, the decriminalisation of the sex trade, institutional discrimination, state violence, and social stigma. These issues impact the global sex trade as well and will continue to facilitate dialogue and intellectual exchange between the different regions. However, sex workers in Latin America have a history of organising that is distinct from the genealogy of sex worker organising in the Global North; the former is ignored and the latter is usually inaccurately assumed to explain sex worker organising in Latin America and the Caribbean. The presence of unique forms of resistance, political advocacy, and commitment to social justice need further visibility. The Latin American and Caribbean sex workers are not the passive recipients and beneficiaries of feminist and worker ideologies from the Global North. Rather, they have long since developed a consciousness and praxis to confront their own issues.

One of the biggest setbacks in the last twenty years has been the neo-abolitionist movement and the conflation of all forms of sex work with human trafficking.[47] These new challenges include practices that seek to ‘rescue’ consenting adults from the sex trade, and policies that ignore their right to self-determination. Nonetheless, non-governmental organisations such as Amnesty International support policies that decriminalise sex work. In 2016, Amnesty International condemned human trafficking and at the same time released a model policy that summons countries to decriminalise the sex trade in order to better protect the health and human rights of sex workers.[48] Other organisations such as the World Health Organization, UNAIDS, the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women, Human Rights Watch, Lambda Legal, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and Freedom Network USA concur with its position.[49]

In 2008, Elena Reynaga, president of RedTraSex, spoke at the first plenary session of the International AIDS Conference dedicated to sex work. She asserted:

Female, male and transgender sex workers are dying because of a lack of health services, a lack of condoms, a lack of treatment, a lack of rights—NOT BECAUSE OF A LACK OF SEWING MACHINES! We don’t want to sew, we don’t want to knit, we don’t want to cook. We want better work conditions. So we demand the following: Abolish all legislation that criminalises sex work. Investigate and condemn violence, abuse and the murder of sex workers. Oppose red-light districts that force us into ghettos and promoting violence and discrimination. Abolish mandatory HIV testing. Abolish the sanitary control card among sex workers. Promote voluntary, free and confidential testing including pre- and post-test counselling. Ensure universal access to prevention, testing, treatment and high-quality care. Provide access to healthcare among migrant and mobile sex workers. Provide access to friendly integral healthcare services, without stigma and without discrimination.[50]

Reynaga’s leadership, along with that of women such as Jacqueline Montero, can infuse public spaces where policy is created with subaltern knowledge of the conditions and solutions to realise the rights of sex workers. The exclusion of sex workers from public life is being defied on multiple fronts, and they are insisting that their voices be heard.

Amalia L. Cabezas is an Associate Professor of Media and Cultural Studies and Gender and Sexuality Studies at the University of California, Riverside. She is the author of the book Economies of Desire: Sex Tourism in Cuba and the Dominican Republic and co-edited Una ventana a Cuba y los Estudios cubanos: A Window into Cuba and Cuban Studies and The Wages of Empire: Neoliberal Policies, Repression and Women’s Poverty. Her journal articles include publications in Social and Economic Studies, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, Latin American Perspectives, Social Identities, and Cleveland Law Review. Her current project addresses sex worker movements in Latin America and the Caribbean. Email: amalia@ucr.edu

[1] All translation from Spanish into English by the author. A Nuñez, ‘Diputada Jacqueline Montero Denuncia Discriminación Trabajadoras Sexuales’, Almomento.net, 23 February 2018, retrieved 4 July 2018, http://almomento.net/diputada-jacqueline-montero-denuncia-discriminacion-trabajadoras-sexuales.

[2] Ibid.

[3] L Murray (Dir.), A Kiss for Gabriela, Miríade Filmes in association with Rattapallax, 2013; M Lamas, El Fulgor de la Noche: El comercio sexual en las calles de la Ciudad de Mexcio, Editorial Oceano de Mexico, S.A. de C.V., Mexico, 2017; C Colimoro, ‘A Prostitute’s Election Campaign’ in G Keippers (ed.), Compañeras: Voices from the Latin American women’s movement, Latin America Bureau, London, 1992, pp. 92-96.

[4] K Hardy, ‘Incorporating Sex Workers into the Argentine Labor Movement’, International Labor and Working-Class History, vol. 77, no. 1, 2010, pp. 89-108, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0147547909990263.

[5] K Kempadoo, ‘Globalizing Sex Workers’ Rights’, Canadian Woman Studies, vol. 22, no. 3, 2003, pp. 143-150.

[6] G Gall, An Agency of Their Own: Sex worker union organizing, John Hunt Publishing, London, 2012.

[7] J Downing, Radical Media: Rebellious communication and social movements, 2nd Edition, Sage, London, 2000.

[8] M Barcia Zequeira, ‘Entre el Poder y la Crisis: Las prostitutas se defienden’ in L Campuzano (ed.), Mujeres Latinoamericanas: Historia y cultura: Siglos XVI al XIX, Havana, 1997, pp. 263-273.

[9] M Beers, ‘Murder in San Isidro: Crime and culture during the Second Cuban Republic’, Cuban Studies, vol. 34, 2003, pp. 97-129.

[10] Barcia Zequeira.

[11] For discussions of responses to regulationism in Latin America, see: S Caulfied, In Defence of Honor: Gender, sexuality and nation in early 20th century Brazil, Duke University Press, Durham, 2000; E J S Findlay, Imposing Decency: The politics of sexuality and race in Puerto Rico, 1870-1920, Duke University Press, Durham, 1999; and T Sippial, Prostitution, Modernity, and the Making of the Cuban Republic, 1840-1920, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2013.

[12] Barcia Zequeira.

[13] Beers, p. 105.

[14] K Bliss, ‘A Right to Live as Gente Decente: Sex work, family life, and collective identity in early twentieth-century-Mexico’, Journal of Women’s History, vol. 15, no. 4, 2004, pp. 164-169, https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2004.0005.

[15] Ibid., p. 167.

[16] A De Liso, ‘How Brazil’s Sex Workers Have Been Organized and Politically Effective for 30 Years’, The Conversation, 15 December 2017, retrieved 12 August 2018, https://theconversation.com/how-brazils-sex-workers-have-been-organised-and-politically-effective-for-30-years-88903.

[17] B Hagenbuch, ‘Rio Prostitutes’ Fashion Line Hits Street Catwalk’, Reuters, 20 January 2007, https://uk.reuters.com/article/oukoe-uk-brazil-fashion-prostitutes/rio-prostitutes-fashion-line-hits-street-catwalk-idUKN2035889120070120.

[18] A Piscitelli, ‘Transnational Sisterhood? Brazilian feminisms facing prostitution’, Latin American Policy, no. 5, 2014, pp. 221-235, p. 224, https://doi.org/10.1111/lamp.12046.

[19] Kempadoo, 2003.

[20] Hardy; See also: J Van Meir, ‘Sex Work and the Politics of Space: Case studies of sex workers in Argentina and Ecuador’, Social Sciences, vol. 6, no. 2, 2017, pp. 1-40, https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6020042.

[21] M Koné, Sex Worker Political Development: From informal solidarities to formal organizing, PhD Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 2014.

[22] M Koné, personal communication, 26 February 2019.

[23] M Koné, ‘Transnational Sex Workers Organizing in Latin America: RedTraSex, Labour and human rights’, Social and Economic Studies, vol. 65, no. 4, 2016, pp. 87-108.

[24] J Loza, ‘Ideas Nacionales en la Escala Regional: La experiencia de acción colectiva transnacional de la RedTraSex en América Latina’, FLACSO/UBA-CONICET, Argentina, retrieved 4 July 2012, http://web.isanet.org/Web/Conferences/FLACSO-ISA%20BuenosAires%202014/Archive/8886d0d9-3dd9-4693-9d10-aa1ac5c7320f.pdf.

[25] RedTraSex, Historias de Trabajadoras Sexuales Empoderadas, 1997-2017, RedTraSex, Buenos Aires, 2017.

[26] RedTraSex, 10 Years of Action (1997-2007): The experience of organizing the network of sex workers of Latin America and the Caribbean, RedTraSex, Buenos Aires, 2007, p. 76.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid., p. 77.

[29] ONUSIDA, ‘La RedTraSex Presenta 20 Años de Logros en la Promoción de los Derechos Humanos de las Tabajadoras Sexuales en América Latina y el Caribe’, ONUSIDALAC, http://onusidalac.org/1/index.php/listado-completo-de-noticias/item/2293-la-redtrasex-presenta-20-anos-de-logros-en-la-promocion-de-los-derechos-humanos-de-las-trabajadoras-sexuales-en-america-latina-y-el-caribe.

[30] K Kempadoo, ‘COIN and MODEMU in the Dominican Republic’, in K Kempadoo and J Doezema (eds.), Global Sex Workers: Rights, resistance, and redefinition, Routledge, New York, 1998, pp. 260-266; D Brennan, What’s Love Got to Do with It? Transnational desires and sex tourism in the Dominican Republic, Duke University Press, Durham, 2004; A Cabezas, Economies of Desire: Sex and tourism in Cuba and the Dominican Republic, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2009.

[31] La Prensa, ‘Es mejor que trabajadoras sexuales medien sus conflictos’, La Prensa, 19 March 2015, http://www.laprensa.com.ni/2015/03/19/nacionales/1801749-csj-es-mejor-que-trabajadoras-sexuales-medien-sus-conflictos.

[32] A Wallace, ‘Nicaragua: El primer país del mundo en entrenar a sus trabajadoras sexuales para resolver conflictos’, BBC Mundo, 10 June 2015, https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2015/06/150609_nicaragua_trabajadoras_sexuales_justicia_aw.

[33] L García, ‘El Objectivo Es Que La Justicia Se Cumpla’, El Nuevo Diario, 5 May 2015, retrieved 4 July 2018, https://www.elnuevodiario.com.ni/nacionales/359415-objetivo-es-que-justicia-se-cumpla.

[34] F Jaugey (Dir.), Girasoles de Nicaragua, Camila Films, Managua, Nicaragua, 2017.

[35] C Varela, ‘Del Tráfico de las Mujeres al Tráfico de las Políticas. Apuntes para una historia del movimiento anti-trata en la Argentina (1998-2008)’, PUBLICAR-En Antropología y Ciencias Sociales, vol. 12, 2013, pp. 35-64.

[36] Hardy.

[37] D Guy, Sex & Danger in Buenos Aires: Prostitution, family, and nation in Argentina, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 1991.

[38] AMMAR, ‘Un Paso Más Para La Descriminalización Del Trabajo Sexual’, AMMAR, 13 July 2018, retrieved 28 July 2018, http://www.ammar.org.ar/Un-paso-mas-para-la.html.

[39] EIKON, ‘La Campaña de las Trabajadoras Sexuales Que Les Valió Un Eikon’, EIKON, 17 October 2015, https://premioseikon.com/la-campana-de-las-trabajadoras-sexuales-que-les-valio-un-eikon-2/; R Radu, ‘Argentina’s Prostitutes–Mothers First Sex Workers Second, The Guardian, 17 June 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jun/17/argentina-prostitutes-advertising-campaign.

[40] J Edwards, ‘These “On The Corner” Ads for Argentine Sex Workers Are Brilliantly Deceptive’, Business Insider, 10 June 2013, https://www.businessinsider.com/ammars-corner-ads-for-argentina-prostitutes-2013-6.

[41] ‘Argentina: Prostitutas Reparten Boletas en el Día del Trabajo’, El Comercio, 2 May 2015, https://elcomercio.pe/mundo/actualidad/argentina-prostitutas-reparten-boletas-dia-189679

[42] S Grattan, ‘“Culture is power”: The Colombian sex workers who launched a newspaper’, The Guardian, 23 April 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/apr/23/colombia-sex-workers-newspaper-la-esquina-bogota.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Semana, ‘El periódico de las trabajadoras sexuales que salva vidas en el barrio Santa Fe’, Semana, 27 April 2018, https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/periodico-la-esquina-hecho-por-trabajadoras-sexuales-trans-del-barrio-santa-fe/565218.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Grattan.

[47] Amnesty International, Sex Workers at Risk: A research summary on human rights abuses against sex workers, Amnesty International, 2016; see also: Varela, 2013.

[48] Ibid.

[49] E Albright and K D’Adamo, ‘Decreasing Human Trafficking through Sex Work Decriminalization’, American Medical Association Journal of Ethics, vol. 19, no, 1, 2017, pp. 122-126, https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2016.19.1.sect2-1701.

[50] E Reynaga, ‘Sex Work and Human Rights’, Presentation at the first plenary session at the XVII International AIDS Conference in Mexico, 6 August 2008, retrieved 4 July 2018, http://redtrasex.org/Sex-Work-and-Human-Rights.

Amalia L. Cabezas

Traducido por Conor Harris

Este artículo busca complicar la idea de que el movimiento de trabajadoras sexuales organizadas tenga su origen en el Norte Global. Desde la Habana, Cuba a fines del siglo diecinueve, trabajadoras sexuales en Latinoamérica y el Caribe se han organizado para reclamar reconocimiento y derechos laborales. Este artículo centra algunos avances del movimiento, tal como la elección de una trabajadora sexual a un cargo público en la República Dominicana, el sistema nicaragüense en lo que trabajadoras sexuales sirven como facilitadoras judiciales de oficio, las redes regionales de organizaciones y las estrategias mediáticas innovadoras para reclamar derechos sociales y laborales. Las trabajadoras sexuales aprovechan de estrategias novedosas diseñadas para trastocar la orden social hegemónica; para disputar las iniquidades, discriminación y injusticias a las que se someten las mujeres cis- y trans- en el comercio sexual; para provocar reflexión crítica y para aumentar la visibilidad de la defensa del trabajo sexual. Nuevos desafíos al movimiento incluyen el movimiento abolicionista, la equiparación de todas formas del comercio sexual con la trata de personas y las prácticas que pretenden “rescatar” a adultas que consienten en participar en el comercio sexual.

En febrero de 2018, un periódico dominicano reportó el apresamiento de trabajadoras sexuales que ejercían en la calle y la respuesta de la diputada Jacqueline Montero:

SANTO DOMINGO, República Dominicana.- La diputada del PRM, por San Cristóbal, Jacquelin Montero, denunció que el apresamiento el pasado fin semana de decenas de trabajadoras sexuales que ejercían en los alrededores de la Basílica Nuestra Señora de la Altagracia en Higuey, es una muestra más de la discriminación y violación de derechos que experimenta ese sector. ‘En la República Dominicana no existe una ley que prohíba el trabajo sexual, por lo tanto, ese apresamiento resultó ilegal’, afirmó.[1]

Resulta sorprendente que un diálogo tal involucre a una Diputada en un país tan profundamente conservador y católico. Respondió como una funcionaria electa del PRM, un partido socialdemócrata dominicano. Montero, quien es entrevistada a menudo por varios medios, comenzó su carrera política en 2010 como miembro del consejo municipal de Haina, una municipalidad fuera de la capital Santo Domingo. En 2016, fue electa diputada al Congreso de la República Dominicana. En esta misma entrevista, Montero añade que ‘es natural el hecho de que las trabajadoras sexuales escojan esa área para ofrecer sus servicios, debido a que es una zona ampliamente transitada’. Su conocimiento íntimo del espacio público del trabajo sexual y las leyes vigentes que regulan su comercio provienen de su historia como ex-trabajadora sexual y directora de una organización de y para las trabajadoras sexuales. En efecto, reportajes periodísticos demuestran que Montero apoya sin reserva los derechos de las trabajadoras sexuales. Además, sus antecedentes como ex-trabajadora sexual la ubican como experta en tanto aboga abiertamente por el cese del acoso, de la criminalización, de la estigmatización y de la violencia contra las trabajadoras sexuales. De hecho, es rutinario que Montero exija al estado que cree trabajos para madres solteras. Durante la entrevista, asevera que ‘la mayoría de las compañeras que realizan el trabajo sexual son madres solteras que deben mantener solas a sus hijos y a las cuales se les hace difícil conseguir empleo, por la discriminación que experimentan en el día a día. El Estado debe garantizarle sus derechos en vez de maltratarlas’.[2]

En Latinoamérica y el Caribe, hay una larga tradición de trabajadoras sexuales que se esfuerzan en reclamar sus derechos sociales y laborales. Montero no es sino la última en entrar al escenario político y referirse públicamente a los asuntos que afectan a las involucradas en el comercio sexual. Trabajadoras sexuales preeminentes, como por ejemplo Claudia Colimoro de la Ciudad de México y Gabriela Leite de Brasil, también han cuestionado las estructuras jurídicas y mores sociales además de postularse por cargo electivo en sus países.[3] Aunque algunos relatos afirmen que la organización política de las trabajadoras sexuales se deba a la influencia norteamericana y europea- la dicha “primera onda” de organización de trabajadoras sexuales[4] - trabajadoras sexuales latinoamericanas y caribeñas tienen una extensa historia propia.[5]

Este artículo documenta la emergencia del movimiento de trabajadoras sexuales en Latinoamérica y el Caribe en el siglo diecinueve. Resulta una historia que cuestiona la literatura sugerente de que las trabajadoras sexuales se organizaran por la primera vez en el Norte Global.[6] Aunque el movimiento del Norte Global ha sido centro de la mayoría de la investigación académica en inglés, aquí me dirijo a Latinoamérica y el Caribe, una región poco investigada dentro de los estudios del trabajo sexual, para subrayar la persistencia histórica de trabajadoras sexuales que se organizan en pro del cambio y de la justicia social.

Abro con unos comentarios acerca de la colectiva de prostitutas que se formó en la Habana, Cuba a fines del siglo diecinueves para luego explorar las culturas de resistencia oposicionales de trabajadoras sexuales en México y Ecuador durante el siglo veinte. También indago la red de organizaciones de trabajadoras sexuales activas en la mayoría de los países latinoamericanos y caribeños y que tiene vínculos a organizaciones globales. Luego, estudio algunas de las estrategias mediáticas innovadoras elaboradas por trabajadoras sexuales en países de habla hispano. Los ejemplos aquí elegidos indican cómo las trabajadoras sexuales desafían a los regímenes hegemónicos del género, del sexo y del trabajo para ofrecer visiones alternativas. Propongo que las redes contiguas actuales, las intervenciones jurídicas pioneras, los medios radicales de trabajadoras sexuales y otras prácticas solidifican la base de un movimiento trans-hemisférico. Resulta crucial que examinemos los avances y desafíos del movimiento para mejor entender las lecciones que rinde a las demás partes del mundo.

He elegido estos ejemplos- usos radicales de los medios, la organización y la intervención jurídica- no por exhaustivos, sino ilustrativos. Fueron elegidos por representar estrategias novedosas formuladas para trastocar el orden social hegemónico, disputar las iniquidades, la discriminación y las injusticias a que sobreviven las mujeres cis- y trans- en el comercio sexual, a la vez que aumentan la visibilidad de la defensa del trabajo sexual y nos incitan a que reflexionemos críticamente.[7]

Este artículo centra sólo algunos ejemplos de países de habla hispana en Latinoamérica y el Caribe. Hace falta más investigación sobre esfuerzos organizativos, en particular etnografías hechas en los países de habla holandés, inglés y francés de la región. Igualmente hace falta más investigación sobre los hombres que ejercen el trabajao sexual y su incorporación al movimiento. Finalmente, convoco más análisis de los usos de los medios sociales para organizar las varias poblaciones de trabajadoras sexuales de la región.

En su mayoría, recuentos de los orígenes del movimiento de trabajadoras sexuales se refieren a precursores del Norte Global, tal como la toma de la iglesia de San Nizier en Lyon, Francia (1975); la fundación de la English Collective of Prostitutes [Colectiva Inglesa de Prostitutas] (1975); y la creación de Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics (COYOTE) [Retira tu Ética Vieja y Gastada] en San Francisco (1973). No obstante, la conceptualización de la prostitución como una forma de trabajo - y no pecado, ni vicio, ni la depravación de ‘mujeres de mala vida’- fue articulada por la primera vez en las Américas por una colectiva de prostitutas caribeñas que se empeñaban en organizarse políticamente para reclamar sus derechos como trabajadoras. En efecto, trabajadoras sexuales en Latinoamérica tienen una larga historia de organizarse, públicamente cuestionando y resistiendo reglamentos y políticas injustas.

Una antecesora poco apreciada del movimiento global por los derechos de trabajadoras sexuales tuvo lugar en Cuba. Tardío en el siglo diecinueve, durante una época de migración europea aumentada y circulación de mujeres por Latinoamérica y el Caribe, muchas mujeres trabajaban en los prostíbulos de la Habana, un destino sexual reconocido desde comenzar la Conquista. Como han descubierto las historiadoras, mujeres migrantes viajaban a la Habana desde Europa, los Estados Unidos, las Canarias, México, Panamá, España y Venezuela para ganarse la vida a duras penas en la zona roja. Algunas de las matronas, o madames, eran adineradas por haber ganado fortunas durante su juventud.[8] Invertían sus ahorros para fundar sitios de entretenimiento que ofrecían prostitución, juegos del azar y baile. Ganaban bastante bien como dueñas de prostíbulos y ellas empezaban a ejercer su poder económico al desafiar las prácticas corruptas de la administración colonial española.

En 1888, un grupo de trabajadoras sexuales habaneras fundó un periódico para dar voz a su perspectiva antigubernamental, llamando a un partido político dirigido por trabajadoras sexuales. Con financiamiento de trabajadoras sexuales adineradas y con edición de un inmigrante español anarquista, Victorino Reineri Jimeno, el periódico servía como medio de protesta al contradecir las leyes discriminatorias y a los funcionarios poco éticos del gobierno colonial.[9] La Cebolla: Periódico ilustrado, órgano oficial del partido de su nombre se distribuía ampliamente por la Habana y otras provincias cubanas promoviendo abiertamente los derechos de prostitutas en la Habana cosmopolita. Su nombre aludía a la fundación de un partido político de trabajadoras sexuales. Sin embargo, las historiadoras no han podido desenterrar pruebas que confirmen la existencia de dicha organización.[10] El periódico se concebía como una publicación por y para prostitutas. Por ejemplo, el periódico abogó por cambios al Reglamento de Higiene Pública, una administración que entre otras cosas pretendía reducir incidencias de enfermedades de transmisión sexual al registrar a las trabajadoras sexuales. Además, pretendía forzarlas a que llevaran carnés y que se sometieran a exámenes ginecológicos. Este sistema de reglamentación estatal del trabajo sexual fue importado de Francia y Inglaterra, para luego ser implementado en las Américas.[11]

En septiembre de ese año, La Cebolla publicó una serie de artículos burlándose de y protestando los reglamentos gubernamentales impuestos a las trabajadoras sexuales que ejercían en prostíbulos, que incluían a altas tasas reguladoras y revisiones médicas obligatorias. Tal como demuestra la historiadora Maria del Carmen Barcia Zequeira, trabajadoras sexuales se definían como una clase marginada y explotada al entenderse como victimas de extorsión constante a manos de autoridades que se esforzaban en regular sus actividades.[12] Una carta sin firma dicha:

Bástele saber á V. E. que el Alcalde Municipal, que como es viejo y regañón no se le para una mosca encima; ha dispuesto que no podamos exhibirnos en la puerta de nuestros establecimientos. ¿Es esto justo? ¿En qué país se prohíbe al industrial exponer al público su mercancía? […] Ha de saber V. E. que las horizontales de esta capital pagamos más contribución al Estado, que la que se necesita para ser elector y elegible. Y sin embargo, aunque contribuímos más que las otras clases á nutrur los fondos del Erario con el sudor de nuestras…..frentes, se nos trata como si fuéramos esclavas, como si estuviésemos fuera de la Ley. Es decir, se nos considera ciudadanas para cumplir deberes, pero no para gozar derechos.[13]

Las ‘horizontales’- el apodo que el periódico puso a las trabajadoras sexuales - no huían de protestar el control de su vida al desafiar una administración explotadora que se apoyaba fiscalmente en los reglamentos promulgados sobre sus cuerpos. Orto artículo proponía formar un gremio de prostitutas para respaldar a sus demandas y luchar para el reconocimiento de los servicios sexuales como una forma de trabajo. Las trabajadoras sexuales aprovechaban del humor y la franqueza para exponer su explotación en la prensa e inspiraron una nueva identidad para las prostitutas - la de trabajadoras.

El espectáculo exigente, así como rebelde de las supuestas “mujeres públicas” que sin pudor se identificaban como prostitutas y la publicación de La Cebolla desafiaban una administración colonial ya hostigada por el movimiento independentista cubano. Los funcionarios contraatacaron y prohibieron el periódico mientras encarcelaron al editor. No obstante, la breve campaña destacó el hecho de que las trabajadoras sexuales dejaban de ser políticamente impotentes, ni fácilmente denigradas. En la Habana a fines del siglo diecinueve las mujeres que se ganaban la vida en la industria sexual imaginaban la formación de un partido político que reclamara sus derechos. Esta intervención significativa fue el génesis del actual movimiento social transnacional de trabajadoras sexuales en Latinoamérica y el Caribe. Como luego detallaré, estas organizaciones han realizado varios de los logros imaginados por las mujeres de La Cebolla.

En el caso de México tenemos un ejemplo de trabajadoras sexuales que se negaban a asociarse con la política laboral. Durante los 1920s y 30s, una época de rápida urbanización y desarrollo nacional en la estela de la Revolución Mexicana, las trabajadoras sexuales comprendían la apariencia de organizaciones políticas como un agravio a su identidad como gente decente. La investigación de la historiadora Katherine Bliss documenta como, en la Ciudad de México, las trabajadoras del comercio sexual insistían en que formaran parte de las comunidades y las casas de las cuales se responsabilizaban. Afirmaban su identidad como sostenes familiares, y por extensión, nacionales en búsqueda de que las reconocieran como gente decente. Cuando los sindicatos laborales radicales intentaron sindicalizarlas para mejorar las condiciones laborales de los prostíbulos y los cabarés, ellas se resolvieron a no dejarse controlar por los organizadores sindicales. Reclamaban una subjetividad política que resultara más flexible y que no las inscribiera en estados permanentes de estigma y bochorno. Contra el discurso del ‘vicio’ o incluso la ‘desesperación individual’ ellas oponían su papel y su identidad como ‘sostenes y madres concienzudas’.[14] Para ellas, el trabajo sexual era una actividad asalariada que emprendían provisionalmente para apoyar a sus familias y, por ende, era asociada con el trabajo reproductivo. Al pregonar el derecho de vivir como gente decente, ellas cuestionaban las condiciones estructurantes de la pobreza asociada al género que las marginaba, así como los mores que las etiquetaban mujeres desviadas conforme al entendimiento hegemónico de la prostitución. Aunque no querían aliarse con los derechos laborales y la sindicalización, no obstante, denunciaban las injusticias que experimentaban.

Paradójicamente, trabajadoras sexuales en la Ciudad de México además rechazaban los esfuerzos del Departamento de Salud Pública como para abolir los establecimientos de comercio sexual, tal como cabarés, y desregular la zona roja. Establece Bliss que ‘aunque muchas mujeres reconocían que su trabajo era indeseable, insistían en que ejercían el trabajo sexual porque eran hijas honradas y madres que apoyaban a familiares necesitados’.[15] Estas trabajadoras también recurrían a la pasión revolucionaria al sostener que su trabajo era en servicio a la nación y a sus familias. Pregonaban que ‘se tiraban a la calle’ y ejercían una profesión que les ponía bajo riesgo de abusa, violencia y enfermedades, para proteger a sus hijos, los lideres y trabajadores del México por venir. En efecto, las trabajadoras sexuales cuestionaban su marginalización afirmando su derecho al trabajo y su identidad social normativa, a la vez que entretejían los campos de la sexualidad, la reproducción social, la nacionalidad y la economía.

Durante los 1980s, las trabajadoras sexuales fundaron varios movimientos políticos comunitarios a través de Latinoamérica. En Uruguay, mujeres que ejercían el trabajo sexual estaban entre los primeros grupos en organizarse, en 1986. Poco después, las trabajadoras sexuales uruguayas obtuvieron seguridad social y beneficios laborales para la salud. Dos trabajadoras sexuales brasileiras, Gabriela Leite y Lourdes Barreto, llevaron a cabo el primer congreso nacional para las trabajadoras sexuales en 1987.[16] Al llegar 2007, las trabajadoras sexuales de Davida, una organización brasileira que defiende los derechos de las prostitutas lanzó la casa de modas Daspu en Rio de Janeiro, siendo esa la primera casa de modas fundada y dirigida por trabajadoras sexuales.[17] Actualmente hay organizaciones para trabajadoras sexuales por todo Brasil, la Rede Brasileira de Prostitutas (Red Nacional de Prostitutas) y la Federação Nacional das Trabalhadoras do Sexo (Federación Nacional de Trabajadoras Sexuales) inclusive.[18]

Uno de los primeros colectivos de trabajadoras sexuales fue organizado en la provincia El Oro, Ecuador, al principio de los 1980. El 22 de junio de 1982, 300 mujeres que trabajaban en prostíbulos se juntaron al formar la Asociación para la Defensa del Mujer de Trabajadoras Sexuales Autónomas y en 1988 hicieron huelga en un intento de conseguir un mejor trato de los dueños.[19] Su éxito animó a la fundación de varios otros colectivos en el país. Cuando las trabajadoras sexuales convocaron el primer congreso nacional en 1993 había once organizaciones comunitarias de trabajadoras sexuales que reclamaban mejoramientos de las condiciones laborales, de la salud y de seguridad. Según Lourdes Torres, la presidenta de la organización de trabajadoras en prostíbulos Asociación para la Defensa de la Mujer, Ecuador tiene por lo menos un colectivo de trabajadoras sexuales para cada provincia.[20]

Es irónico que la crisis de VIH/SIDA durante los 1980 forzó que los gobiernos y asociaciones supranacionales de la salud hicieran caso del papel que las/-os trabajadoras/-es podían tener al prevenir y erradicar el virus. Según la investigación de Mzilikazi Koné, el comienzo de la cooperación con las trabajadoras sexuales giraba en torna a la prevención de y el empoderamiento frente a VIH.[21] La salud sexual era primordial, y el empoderamiento y la organización llegaron a través de ese modelo inicial centrado en la salud sexual.[22] Las trabajadoras sexuales seguían siendo el enfoque de intervenciones estatales para eliminar las enfermedades venéreas, sin embargo, estas prácticas problemáticas juntaron a las trabajadoras sexuales, facilitando más organización. Por ejemplo, reuniones regionales dieron lugar a la fundación de redes transnacionales. Actualmente estas redes están vinculadas a similares esfuerzos en países más desarrollados y señalan la entrada de Latinoamérica y el Caribe a la escena global en la defensa de los derechos de trabajadoras sexuales.

La existencia de asociaciones transnacionales comenzó en 1997 en Costa Rica cuando nació La Red de Mujeres Trabajadoras Sexuales de Latinoamérica y el Caribe (RedTraSex) como una asociación no gubernamental transnacional de grupos de trabajadoras sexuales en la región, para luego ir acumulando influencia política. RedTraSex tiene sede en la Argentina y junta a asociaciones de catorce países: Argentina, Brasil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, la República Dominicana, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, México, Nicaragua, Panamá, Paraguay y Perú.[23] La socióloga Jorgelina Loza explica que ‘el reclamo central de las mujeres que integran RedTraSex es que los estados-naciones las reconozcan como sujetos legítimos, es decir, como trabajadoras con derechos acerca de condiciones laborales y de beneficios sociales: alojamiento, salud, jubilación y pensiones’.[24] A través de una aproximación feminista que centra los derechos, RedTraSex coordina programas que buscan juntar a las trabajadoras sexuales alrededor de los asuntos que les afectan las vidas. Estos incluyen el apoyo para mejor acceso al cuidado médico libre de discriminación, iniciativas en contra de la violencia, ambientes laborales seguros, la salud sexual, y las movilizaciones que se oponen a la trata de personas.

RedTraSex ha mejorado la visibilidad, la influencia y el activismo a través de varios esfuerzos. Aunque no resulte una lista exhaustiva, aquí destaco algunos logros significativos facilitados por la colaboración transnacional. En primer lugar, las conexiones engendradas en vínculos transnacionales, al nivel regional e internacional, han fortalecido la imagen y la legitimidad de las activistas además de facilitar una plataforma para denunciar la violencia rutinaria con que se enfrentan las trabajadoras sexuales. Samantha Carrillo, de la Organización Mujeres En Superación, refleja así sobre su influencia creciente en Guatemala: ‘Éramos un trío de locas pensando en que algún día íbamos a tener una casa y que algún día nos íbamos a sentar con los funcionarios a hablar acerca de nosotras como trabajadoras sexuales’. Añade que:

Cada año, cada día, cada paso que damos, ya no somos un trío de locas. Hoy somos treinta y cinco compañeras trabajadoras sexuales en el día a día, trabajando en la práctica, arreglando con los directores de centros de salud, hablando con diputados, con ministros y hablando de cómo queremos cambiar no sólo las condiciones laborales sino también las condiciones en salud y también nuestros derechos.[25]

María Consuelo Raymundo, afiliada a Orquídeas del Mar en El Salvador, hace eco de este sentimiento cuando afirma que ‘[l]a RedTraSex nos proporciona mayor visibilidad con las instituciones gubernamentales.[26] Si estamos solas no pasa nada, pero cuando estamos unidas en tantos países la gente tiende a tomarnos en serio’. Tal respeto sería de difícil alcance sin el poder y la fuerza de una red regional.

En segundo lugar, las organizaciones priorizan un modelo de gobernanza que encarga a las trabajadoras de dirigir el movimiento.[27] Por lo tanto, la dirección se compone principalmente de trabajadoras sexuales, incluso pese a que carezcan de una educación formal. Además, aproximaciones interculturales y transnacionales han acarreado nuevas tácticas al paisaje nacional. Como reporta miembro Ángela Villón, representante de Miluska Vida y Dignidad, organización peruana de trabajadoras sexuales, ‘[v]er cómo funcionan las cosas en otros países permite encontrar modelos que puedes ir adaptando a tu realidad’.[28] Aunque se enfrenten con barreras lingüísticas, diferencias culturales y raciales, dificultades tecnológicas en la comunicación, dificultades tecnológicas de comunicación e incertidumbre financiera, las socias con sus esfuerzos están formando espacios públicos y políticos al nivel nacional, así como regional para gente en la industria sexual.

La RedTraSex se compromete con varios formas y estilos de apoyo para las trabajadoras sexuales. Incluyen a campañas comunicativas, el desarrollo de campañas de concienciación dirigidas a actores nacionales y la fundación de y el respaldo para organizaciones comunitarias de trabajadoras sexuales. También dirige investigación y desarrolla informes de situación sobre asuntos claves tal como los derechos sexuales y reproductivos, la violencia, los derechos laborales y la distinción entre el trabajo sexual autónomo y la trata de personas.[29]

Otra red regional, Plataforma Latinoamericana de Personas que Ejercen el Trabajo Sexual (PLAPERTS) tiene sede en Ecuador. Organizaciones de Brasil, Ecuador, México y Perú fundaron esta sucursal de la Global Network of Sex Work Projects en 2014. Tal como la RedTraSex, organizaciones miembros de la plataforma llaman al reconocimiento del trabajo sexual como ocupación legítima, luchan para mejorar las condiciones laborales de las trabajadoras sexuales y informan a sus miembros sobre sus derechos. Además, hay organizaciones regionales más concentradas. En el Caribe, La Coalición de Trabajadoras Sexuales Caribeñas (CSWC) fundada en 2011, junta a trabajadoras sexuales de países caribeños de habla inglés, holandés y español. Pequeños grupos de Antigua, Belice, Granada, la República Dominicana, Guyana, Jamaica, Surinam y Trinidad y Tobago componen la CSWC. Incluye la organización caribeña regional Trans en Acción, que apoya a las mujeres trans que ejercen el trabajo sexual. La mayoría de las alianzas socias trabajan principalmente con las mujeres cis y trans que ejercen el trabajo sexual sin que importe su preferencia sexual, aunque algunas si incorporan a hombres.

Tanto PLAPERTS como RedTraSex han instigado nuevos paradigmas para mujeres que trabajan en la industria del sexo. Estos paradigmas combinan comunalidad, colaboración y nuevas subjetividades sociales y políticas. Como trabajadoras, feministas y ciudadanas que se merecen las protecciones de los derechos humanos, están comprometidas con el apoyo y respeto mutuos. Las colectivas distintas también se dedican al empoderamiento de trabajadoras sexuales, así como a lograr cambio legislativo en sus países respectivos, como veremos en adelante.

Esta red de organizaciones de trabajadoras sexuales que ha florecido desde los 1980s también participa activamente en la sociedad civil- principalmente a través del fundar organizaciones no gubernamentales- además de entrar a la política. Jacqueline Montero, por ejemplo, más allá de servir como una Diputada electa en el Congreso dominicano es la presidenta de la organización de trabajadoras sexuales Movimiento de Mujeres Unidas (MODEMU), una organización no gubernamental fundada por el Centro de Orientación e investigación Integral (COIN). COIN es una organización comunitaria basada en Santo Domingo que apoya a las trabajadoras sexuales en vías de rendir educación sexual más segura a poblaciones vulnerables.[30] Fundada en 1996, MODEMU era la única organización de trabajadoras sexuales en todo el país hasta el 2016, cuando exmiembros del MODEMU fundó un nuevo grupo bajo la dirección de Miriam Altagracia Gonzalez Gómez, una de las fundadoras del MODEMU. La Organización de Trabajadoras Sexuales (OTRASEX) trabaja íntimamente con la RedTraSex y recientemente llevó a cabo investigaciones sobre la violencia policiaca que sufren las trabajadoras sexuales. También ha dado lugar a talleres educativos con miembros de las fuerzas armadas. El hecho de que haya dos organizaciones de trabajadoras sexuales en un país pequeño atestigua a la autodeterminación así como a la heterogeneidad de perspectivas dentro del movimiento para derechos sociales, laborales y políticos.

Un principio central del movimiento para los derechos de las trabajadoras sexuales es la aceptación oficial del trabajo sexual como trabajo. Más allá de los esfuerzos de redes en Latinoamérica y el Caribe, mujeres que ejercen el trabajo sexual luchan para visiones alternativas de la justicia en países individuales. Últimamente, la organización Girasoles de Nicaragua ha avanzado en la lucha para el reconocimiento de sus derechos como trabajadoras precarias y ha colocado a las trabajadoras sexuales como parte esencial del sistema jurídico.

Fundada en noviembre de 2007, actualmente Girasoles de Nicaragua cuenta con más que 2.300 miembros. La colectiva, junta con la Corte Suprema del país iniciaron el primer programa de facilitadoras judiciales que son también trabajadoras sexuales. Este modelo de mediación reduce el número de casos en las cortes y mejora la comunicación entre las trabajadoras sexuales y el sistema jurídico. Nicaragua es el primer país del mundo en entrenarles a las trabajadoras sexuales a resolver conflictos dentro de su jurisdicción. Oficialmente entrenadas y acreditadas por la Corte Suprema, dieciocho trabajadoras sexuales trabajan con la Administración de Justicia como facilitadoras judiciales para mediar conflictos relacionados con el trabajo sexual y para prevenir y disminuir la violencia. La Presidenta de la Corte Suprema, Alba Luz Ramos, dijo en una entrevista que ‘es la mejor manera de hacerlo, porque ellas [las trabajadoras sexuales] a veces se sienten discriminadas por lo demás de la comunidad’.[31] Ofreciendo un ejemplo de la eficacidad del programa, la presidenta de Girasol María Elena Dávila dijo en una entrevista que las facilitadoras judiciales pudieron ayudar a una colega de 23 años que fue apuñalada por un cliente. Encarcelaron al cliente y las facilitadoras supervisaron el proceso ‘para asegurar que la policía y la medicina forense cumplieran con sus deberes’.[32] Luego explicó cómo incorporar a defensoras de las trabajadoras sexuales es un paso esencial del proceso, ya que ayuda a garantizar que la policía y el sistema jurídico no victimicen a las trabajadoras sexuales.

En una entrevista de 2015, preguntaron a Dávila cómo se sentía acerca del hecho de que las trabajadoras participaran como facilitadoras judiciales. Contestó que:

Ya nos sentimos reconocidas, pero no tenemos un documento que diga a partir de este día las trabajadoras sexuales gozan de los mismos derechos que el gremio de los trabajadores. Lo vamos a lograr, porque ese es el reto, pero no puedo decir si hoy o mañana… Ahí estaríamos más felices de los que estamos ahora. Ese sí sería el punto final, pero cada derecho va llevando a que demandés otro.[33]