ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

Ntokozo Yingwana, Rebecca Walker, and Alex Etchart

In South Africa, the conflation of sex work with human trafficking means that migrant/mobile sex workers are often framed as victims of trafficking while arguments for the decriminalisation of sex work are discounted due to claims about the risks of increased trafficking. This is despite the lack of clear evidence that trafficking, including in the sex industry, is a widespread problem. Sex worker organisations have called for an evidence-based approach whereby migration, sex work, and trafficking are distinguished and the debate moves beyond the polarised divisions over sex work. This paper takes up this argument by drawing on research with sex workers and a sex worker organisation in South Africa, as well as reflections shared at two Sex Workers’ Anti-trafficking Research Symposiums. In so doing, the authors propose the further development of a Sex Work, Exploitation, and Migration/Mobility Model that takes into consideration the complexities of the quotidian experiences of migration and selling sex. This, we suggest, could enable a more effective and productive partnership between sex worker organisations and other stakeholder groups, including anti-trafficking and labour rights organisations, trade unions, and others to protect the rights and well-being of all those involved in sex work.

Keywords: sex work, human trafficking, migration, South Africa, decriminalisation

Please cite this article as: N Yingwana, R Walker, and A Etchart, ‘Sex Work, Migration, and Human Trafficking in South Africa: From polarised arguments to potential partnerships’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 12, 2019, pp. 74-90, www.antitraffickingreview.org.

Discussions about sex work in South Africa remain polarised and highly influenced by concerns about human trafficking. In particular, claims that decriminalisation of sex work would lead to an increase in the trafficking of women and children into the sex industry have prevented the consideration of a rights-based approach to sex work. In addition, much of the evidence-based research indicating the importance of decriminalisation to ensure access to healthcare, protection from violence, and a reduction in discrimination and stigma against sex workers has been eclipsed by a moral panic about ‘sex trafficking’. This is despite the lack of evidence to suggest that there are high levels of trafficking into the sex industry in South Africa.[1]

Recognising that the policy on sex work remains largely entangled with the trafficking discourse, this paper argues for a different approach. We assert that there is a need to acknowledge the complexities of and contradictions in the everyday experiences of migration and selling sex in order to show how sex workers can be central to the fight against human trafficking. We argue that this would enable different potential partners—including anti-trafficking, migrant rights, and labour rights organisations and trade unions—to recognise sex worker organisations as allies, and engage with them in an effort to strengthen workers’ rights and improve protections in unregulated labour sectors. While such partnerships remain uneasy due to the exclusion of sex workers from discussions of labour rights and women’s ecomomic empowerment, there is a clear need for such engagement and for considering how these partners can move forward.

This argument is supported by the findings of a research project conducted in South Africa as part of a seven-country study published in 2018 by the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW). The study investigated how sex worker rights organisations deal with abuse and exploitation (including human trafficking) in the sex industry.[2] One of the authors of this article conducted the research in South Africa. This paper presents key findings of that research, alongside reflections shared at two Sex Workers’ Anti-trafficking Research Symposiums, which were held in Cape Town and Johannesburg in May and July 2018 as follow-ups to the GAATW study. We conclude by proposing the further development and implementation of the Sex Work, Exploitation, and Migration/Mobility Model as a way of helping to distinguish between migrant/mobile sex work and human trafficking for sexual exploitation, as well as, crucially, identifying where there may be overlap.

In South Africa, under the Sexual Offences Act 23 of 1957 (last amended in 2007), all aspects of sex work are criminalised, which includes the buying, selling, and .[3] A growing body of research indicates how criminal responses to sex work and sex workers—the majority of whom are internal and cross-border migrants—result in an increase in sex workers’ vulnerabilities to rights violations.[4] This includes gender-based violence (GBV), interpersonal violence, behavioural violence (exploitation by brothel owners and pimps, attacks from clients, and abuse by the police or members of the public), and structural violence (discrimination within and challenges accessing healthcare, legal support, education, etc.).[5] These vulnerabilities and risks are experienced by persons selling sex globally, particularly in criminalised contexts.[6]

Despite the many risks associated with selling sex, research also shows that, in the context of high levels of poverty and unemployment, sex work remains a viable livelihood strategy.[7] Studies indicate that sex workers with a primary school education are able to earn nearly six times more than the typical income earned in more formal employment (such as domestic work), and women selling sex are normally heads of households supporting an average of four persons.[8] Although able to support families and generate income, individuals selling sex are not recognised as legitimate workers who contribute to the economy. Rather, they are framed as deviants, criminals, or (at best) victims, thus simplifying and often misrepresenting their complex lived realities.[9] Various sex worker rights organisations, civil society groups, and academics have therefore called for the decriminalisation of sex work. They argue that, under this legal model, sex workers would be able to access basic human rights, healthcare, and social support, while being able to work safely. This call is backed by a number of international organisations, including Amnesty International, Open Society Foundations, and the International HIV/AIDS Alliance.[10]

However, recommendations made by a recent report by the South African Law Reform Commission (SALRC) on the country’s legislative reform process on the regulation of sex work rejected the decriminalisation model.[11] Instead, the SALRC suggested either the continuation of the criminalisation of all aspects of sex work, or the adoption of partial criminalisation (the so-called ‘Swedish Model’).[12] This was based on a number of key claims about sex work, and the assumed connections among sex work and human trafficking, (illegal) migration, and the exploitation of children in the sex industry.[13] Similar claims were also made in reports used to inform the development of The Prevention and Combating of Trafficking in Persons Act, which was implemented in 2015.[14] While there is little robust and reliable research that can support these claims, there has been a growing body of empirical work, which documents the significant harms experienced by sex workers under criminalisation, and as a result of certain anti-trafficking measures.[15] The 2018 GAATW research, and the follow-up Sex Workers’ Anti-trafficking Research Symposiums, as discussed below, supported these findings.

For the GAATW study, the South African researcher conducted fieldwork in Johannesburg and Capetown.[16] These two cities were selected because of their central roles in South Africa’s sex work, migration, and trafficking historical landscapes and debates.[17] In each city, a focus group was facilitated with service users of the Sex Worker Education and Advocacy Task Force (SWEAT), who were predominantly members of Sisonke, South Africa’s national sex worker movement, and either current or former sex workers.

There were 21 focus group participants in total—fourteen in Johannesburg, and seven in Cape Town—and two interviews with individual sex workers (also in Cape Town). The participants in this study were mostly black women, including two transgender women and two migrant sex workers from Zimbabwe. The Johannesburg respondents were largely brothel-based, while the Cape Town respondents were mainly street-based sex workers. All were over 18 years of age. In addition, eleven interviews were conducted with representatives of partner and allied organisations. Six initial interviews were conducted with Sisonke and SWEAT; two with Sisonke peer educators in Johannesburg, and one each with the SWEAT director, the SWEAT Helpline coordinator, the SWEAT Human Rights and Lobbying officer, and the coordinator of the Asijiki Coalition for the Decriminalisation of Sex Work (who are all based in the same Cape Town office). Four interviews were conducted with representatives of allied organisations: the Women’s Legal Centre (WLC), Sonke Gender Justice, Sediba Hope Medical Centre, and the South African National Human Trafficking Resource Helpline. The focus groups and interviews were conducted in English, isiZulu, or isiXhosa (local languages). Respondents were encouraged to engage in the language they are most comfortable with, so the interviews and focus groups often toggled between the three. In focus groups, participants also assisted each other with translations where needed. The initial findings of this country study were shared with SWEAT and Sisonke to ensure there was no misrepresentation. During this review process, the National Coordinator of Sisonke gave additional insights, which were also included in the final report.

The research findings were supported by reflections shared at the follow-up Sex Workers’ Anti-trafficking Research Symposiums, co-hosted by SWEAT, Sisonke, and GAATW. The Cape Town symposium was held at the SWEAT/Sisonke office on 31 May 2018, and the Johannesburg symposium at the Tshwaranang Legal Advocacy Centre (TLAC) on 6 July 2018. The first symposium drew almost 20 participants, while just under 40 attended the second. Those in attendance at both symposiums included sex workers (Sisonke peer educators and members), researchers (from the African Centre for Migration and Society at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg), government officials (from the Department of Social Development and the Office of the Premier of Gauteng Province), members of civil society organisations (such as the South African National AIDS Council and Sonke Gender Justice), an anti-trafficking organisation (A21’s South African National Human Trafficking Resource Helpline), and a children’s rights organisation (Molo Shongololo).

The key findings from GAATW’s South African study and the reflections shared at both research symposiums affirmed that the conflation of sex work and human trafficking creates challenges when trying to address trafficking in the sex industry. This conflation not only makes it difficult to effectively identify and deal with such cases, but also causes tensions and distrust between sex worker rights and anti-trafficking activists.

The country findings indicated that, even though the sex worker respondents were not necessarily aware of national or international legislation on human trafficking, the majority understood it as some form of coercion linked to movement, as explained by one of the Johannesburg focus group participants, Nonhle Zulu, who simply stated, ‘[f]or me, human trafficking is when someone takes me where I do not want to go’.[18] In addition, the sex worker respondents also tended to speak about human trafficking interchangeably with the labour exploitation they experienced at the hands of brothel owners/managers in the form of overwork, little or no pay, restricted movement, and extortion through hefty fines. The sex worker respondents also agreed that, even though trafficking does occur in the sex industry, it is not as prevalent as other forms of human rights violations they face. Nevertheless, during the Johannesburg focus group, some sex workers began recalling trafficking cases they had come across in the course of their work.[19]

Thulisile Khoza—a former Sisonke peer educator in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN)—described a case that started in 2012 when she and her colleagues helped police identify 38 young women and girls (some as young as 12 years old) who had been trafficked and forced into selling sex at a Durban brothel. Khoza explained that the women had also been forced to take drugs until addicted, so that the traffickers could keep them under their control. Throughout the investigation and trial, the case received a great deal of media coverage, and much was made of the fact that the owner of the lodge where the women had been kept was a doctor. However, the media did not mention the Sisonke sex worker peer educators who had been instrumental in unearthing the case. Khoza described how Sisonke came across the trafficked women:

We were doing outreach in KZN, it was at night, around the beach area—Point Beach area. So we could see these young girls around the streets, and then when we were trying to talk to them, they were shaky, and you could see they are scared to talk. And they kept on looking around to see if the people who are actually looking after them could see them. Then afterwards, when we saw that they were scared, we said, ‘Okay fine, we’re only going to give you the condoms. Then we’ll take our pamphlets and write the numbers on the pamphlet, and then we’ll take the pamphlet and throw it in the dustbin’. When we did that, apparently the girl—because she really wanted to be helped—whilst her pimps were not looking, she went to the dustbin and took out the pamphlet with the numbers and then she actually called Cape Town. And then, when she called Cape Town, the Sisonke helpline, that’s when the case was actually brought forward to us. Then, after that we took up the case, called the police, and the police actually did the investigation; they actually went to the place where the pimps were keeping the young women.

The doctor and his wife were acquitted, but three of their employees were found guilty on charges of human trafficking for sexual purposes, sexual exploitation of minors, racketeering, running a brothel (for ten years), living on the earnings of sex work, and dealing in cocaine. In November 2016, the three men were each sentenced; the main accused received 35 years in prison, while his two accomplices each received 25.[20]

The sex worker respondents also reported occasionally coming across young women working in the industry that they believed were under the age of 18, but they mostly expressed feeling helpless to do much about it. They shared that the young people tended to maintain that they are selling sex by choice, and that they taunted the older sex workers, accusing them of being jealous because they could not attract as many clients as when they were younger. If the older sex workers tried to raise their concerns with their brothel owners/managers or pimps, they were simply told that the sex industry needed the girls for business, and were threatened with eviction if they pursued the matter further. Not wanting to risk their livelihoods (through evictions or police raids), they were forced into silence.

These stories shared by sex workers further illustrate the extent to which criminalisation creates the conditions in which concerned sex workers are reluctant to report such cases to the police. However, these circumstances have not deterred sex worker rights groups and organisations from attempting to address situations of exploitation and human trafficking in the industry.

The stories that emerged from the GAATW study were also reflected on at both Sex Workers’ Anti-trafficking Research Symposiums. The research symposiums had two purposes. The first was to provide a platform on which GAATW’s South African research findings could be presented and discussed with the attending sex workers, academics, activists, representatives of anti-trafficking NGOs, and government officials. The second purpose was to facilitate a more nuanced discussion about trafficking and, more specifically, ‘to analyse the difference between trafficking and sexual exploitation within the sex work industry’.[21] Such a discussion would take into consideration the continuum of varying degrees of choice and coercion that sex workers may experience when entering sex work. It would also acknowledge that, in certain instances, a sex worker who might have initially been tricked or coerced into the industry might later decide to continue working in it.

For example, three sex workers who participated in the Johannesburg focus group as part of the GAATW study reported having been enticed, misled, or coerced into sex work by either a friend or family member. However, they explained that, once they found themselves earning enough to provide for their children and families, they opted to continue working in the industry.[22] These accounts are consistent with Joanna Busza’s caution against the dangers of oversimplifying the anti-trafficking discourse in sex work:

[S]ex workers’ experiences fall along a continuum, with women who have undergone widely varying degrees of choice or coercion… [A]dditionally, individual sex workers may go through different phases; for example, a woman who was originally tricked into selling sex might independently choose to continue doing so. Initial pathways into sex work, therefore, do not necessarily define sex workers’ current perceptions, motivations, or priorities…[23]

This clearly demonstrates the need to consider a more nuanced model of understanding human trafficking in the sex industry—one that takes into consideration sex workers’ lived realities. What is needed is a model that makes a clear distinction between human trafficking and sex work, while also recognising the situations where they may overlap.

As the Durban case study discussed above illustrates, sex worker rights groups such as SWEAT and Sisonke can play an integral role in addressing human trafficking in the sex industry, given that they and their service users/members are often best positioned to identify such cases. However, this is not without its difficulties. In both the GAATW country study and the follow-up research symposiums, SWEAT/Sisonke staff expressed some frustration with the lack of trust and cooperation anti-trafficking organisations and government officials often exhibited when working with them on suspected trafficking cases. They argued that this distrust not only made it difficult to effectively identify and deal with cases of trafficking, but it also resulted in tensions between sex worker rights and anti-trafficking activists.

The notion that supporting sex workers’ access to human rights somehow automatically makes a person pro-trafficking, or that fighting human trafficking means you are anti-sex work, is fundamentally flawed. Sex worker rights activists also oppose human trafficking, as the crime violates sex workers’ human rights, too. In the same vein, some anti-trafficking activists do engage with sex workers as they recognise that this contributes to combating human trafficking in the sex industry. However, this has not been the experience of SWEAT staff. Around 2010, SWEAT joined the Western Cape Counter-Trafficking Coalition, in order to strategically partner with anti-trafficking organisations that have the resources and mandate to deal with trafficking. However, the ideological differences on sex work that existed among the Coalition member organisations at times manifested in blatant hostility against SWEAT. SWEAT’s former director Sally-Jean Shackleton explained:

One of the organisations, in fact, was publishing information on their website that was inflammatory about SWEAT. It was saying that we were funded by pimps and traffickers, so it just got untenable. We couldn’t be in that situation and be genuine.[24]

Shackleton added that anti-trafficking stakeholders tend to take a ‘rescue approach’ instead of being person-centred, and that they also often work from an anti-sex work ideological standpoint. As a result, in November 2012, SWEAT, WLC, and Activists Networking Against the Exploitation of Children (ANEX) decided to come together to draft a Counter Sexual Exploitation in Sex Work Protocol, which would guide them in coordinating appropriate and sensitive interventions in addressing exploitation in the sex industry, including, but not limited to, human trafficking. This draft protocol proposes that the initial assessment take a two-pronged approach—individual and situational—which takes into consideration the presumed trafficked person’s immediate safety and health needs in relation to their socio-economic environment, so as to arrive at an appropriate and individualised response.

Even though it was never finalised, SWEAT and Sisonke have adopted some of the draft protocol’s elements when cordinating certain interventions. Yet the fact that the protocol remained in draft form for all these years indicates the need for stronger partnerships with anti-trafficking organisations and other stakeholders when designing, implementing, and funding such interventions. In particular, labour organisations, trade unions, and migrant rights groups could play a central role in helping to address cases of exploitation and trafficking in sex work. The draft protocol was discussed at the two symposiums and led to the development of the Sex Work, Exploitation, and Migration/Mobility Model. We argue here that the model helps to shift the sex work, migration, and human trafficking discourse in South Africa to a more productive and inclusive space, as explored below.

The Sex Work, Exploitation, and Migration/Mobility Model is based on the ‘polymorphous paradigm’ approach to understanding sex workers’ lived experiences.[25] Unlike the ‘oppression model’, the paradigm is evidence-based, and recognises sex workers’ varied experiences. As Ronald Weitzer explains:

‘[p]olymorphism is sensitive to complexities and to the structural conditions shaping the uneven distribution of workers’ agency and subordination. Victimization, exploitation, choice, job satisfaction, self-esteem, and other factors differ between types of sex work, geographical locations, and other structural conditions.’[26]

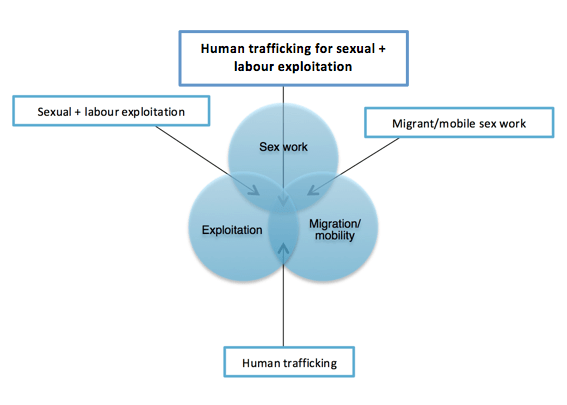

In addition, the proposed model also draws inspiration from Hila Shamir’s argument for the adoption of a labour paradigm when dealing with human trafficking.[27] However, under the current criminalisation regime, it would be difficult to effectively apply a labour approach to trafficking that targets the exploitative structures within the sex industry; hence, our concurrent call for the decriminalisation of sex work. The proposed model, therefore, aims to complicate understandings of sex work, migration, labour, and human trafficking in order to try and capture the varied daily experiences of people selling sex. This is illustrated in the Venn diagram below.[28]

The above model was originally derived from the Coercion—Migration—Sex Work (CO-MI-SE) Model developed by the Sex Worker’s Opera[29] while workshopping with feminist, LGBTQ+, and diasporic groups in order to deconstruct and complexify the assumptions embedded in the overuse of the word ‘trafficking’, and the violences that are carried out as a result. For instance, under the UK’s ‘hostile environment [towards migrants]’, trafficking policy and legislation is often used to humiliate, arrest, and forcibly deport migrant sex workers who are all assumed to be ‘victims’.[30]

The distinct spaces in both the CO-MI-SE model and the Sex Work, Exploitation, and Migration/Mobility Model allow us to explore specific convergences. For instance, exploring where migration meets sex work with no exploitation, opens conversations around the causes of migration (such as conflict, poverty, and the search for better livelihoods), the challenges associated with irregular migration, and the subsequent lack of documentation, and resultant barriers in accessing services.[31] For while sex work is recognised as a highly mobile industry, migrant sex workers are rarely discussed or included in discussions regarding migrant rights and vulnerabilities.[32]

Exploring where sex work meets exploitation without migration allows us to investigate the spectrum of rights violations within sex work from coercion and controlling partners to bad working conditions and fines at workplaces. This approach then does not connect the exploitation and rights violations innately to migration and movement. Finally, exploring where migration meets exploitation without sex work allows us to acknowledge that migrants are sometimes forced into different types of labour,[33] yet the common responses to these incidents are not to criminalise the respective industries, but rather to improve labour laws, practices, and structures. Such situations would include migrants who indebt themselves to dubious third parties, in order to be smuggled into a destination country, while holding little information about the work they will be forced to do upon arrival to pay off that debt.[34]

Therefore, taking the membranes connecting the intersections of both models’ Venn diagrams as blurry spectra in and of themselves allows us to engage in critical conversations about intention and consent in migrant/mobile labour. Building on the CO-MI-SE model, we argue that the Sex Work, Exploitation, and Migration/Mobility Model offers an accessible way of understanding the definition of ‘trafficking in persons’ adopted in the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (the UN Trafficking Protocol).[35] In particular, it offers governments and civil society actors a way to better distinguish between migrant/mobile sex work and human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation, as well as to recognise where there may be overlaps.

When applying the Sex Work, Exploitation, and Migration/Mobility Model, we consider sex work, migration/mobility (movement), and exploitation (violence) as three circles overlapping with each other to form a triangle. Where the overlapping circles meet, four distinct possible conditions exist. Where sex work overlaps with some form of movement, it is a situation of migrant/mobile sex work. In this instance, a sex worker might be selling sex away from their home, or while in transit, as in the case of sex workers operating along long-distance truck routes. Should the selling of sex overlap with violence or exploitation, we could be dealing with sexual and/or labour exploitation in sex work. A possible scenario under these conditions could be a brothel manager extracting exuberant rent from their staff, or forcing them to service clients they are uncomfortable with. Finally, when migration/mobility overlaps with exploitation or violence, we could be encountering a case of human trafficking. However, it is important to note that, based on the proposed model, this form of trafficking currently sits outside of commercial sex. So only when all three circles intersect in the centre do we find a clear case of human trafficking for the purpose of sexual and labour exploitation in sex work.

During both Sex Workers’ Anti-trafficking Research Symposiums, participants were asked to consider the model’s application to specific scenarios of possible sexual exploitation cases in sex work.[36] In groups, the symposiums’ attendees were encouraged to collaboratively discuss and design appropriate, sensitive, and innovative interventions, if at all needed, to the cases provided. For example, one of the groups at the Cape Town research symposium was asked to develop an appropriate response to the case of an adult consenting woman sex worker whose intimate partner is also her pimp. The couple decides to move to Johannesburg in the hope of improving their business. However, shortly after arriving in the city, their relationship starts to deteriorate; the partner starts imposing clients onto her she is uncomfortable servicing, taking most of her earnings, and being violent.

The symposium attendees agreed that, although at first sight, this might come across as a classic case of trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation, the case was complicated and a standard anti-trafficking intervention might not be the appropriate approach to take in this instance. First, the woman willingly travelled to Johannesburg to engage in sex work; she was not forced, deceived, or coerced to migrate or to sell sex. Second, since she is in an intimate relationship with her pimp, it is difficult to know if she would want assistance or not as she may not wish to leave him or have him arrested for domestic abuse. While this was unclear, what was certain was that, if she wanted assistance, this would not be in the form of ‘rescue’ as a trafficked person. After some discussion, the group decided that she would first have to be consulted as to whether she wanted to be assisted, and if so, how. This would need to be done sensitively in the form of a confidential interview and person-centred assessment by (possibly) one of the SWEAT/Sisonke counsellors. The symposium attendees insisted that only after this consultation could an appropriate response be designed and implemented.

This discussion around one possible case is illustrative of Busza’s argument about the varying degrees of choice and coercion that sex workers may experience in the industry.[37] Furthermore, it also highlights the importance of recognising the intersections—and the distinctions—among migration, sex work, and trafficking. For where anti-trafficking measures push for the rescue of all those involved in the sex industry, regardless of agency or choice, the human rights of people who sell sex are not only violated, but the space for their voices and for them to challenge the misrepresentations of their lives and work is also reduced.

The participants were also asked to identify possible stakeholders, potential referral networks, and essential resources that could be mobilised in the finalisation and implementation of the draft Counter Sexual Exploitation in Sex Work Protocol, which would guide them in coordinating such responses. As a rights-based response tool, the draft protocol aims to address exploitation in the sex industry in its entirety, but without perpetuating the conflation of sex work and human trafficking. The model and the protocol are currently being workshopped and further developed in collaboration with SWEAT, Sisonke, civil society partners (including anti-trafficking organisations), and government officials who attended the anti-trafficking research symposiums, and also in consultation with one of the co-authors of this paper who conceptualised the CO-MI-SE model.[38]

The conflation of sex work and human trafficking undermines the calls for decriminalisation of sex work and estranges crucial actors in the fight against trafficking. While recognising that human trafficking can and does occur in South Africa’s sex industry, we suggest that the Sex Work, Exploitation, and Migration/Mobility Model can improve the understanding of and responses to human trafficking. First, the model enables sex workers and sex worker rights groups, such as SWEAT and Sisonke, to be recognised as legitimate stakeholders in anti-trafficking work. Second, the model can help in identifying and addressing more common—even if less sensationalistic—human rights violations in sex work, such as long working hours, non-payment of wages, and violence perpetuated by clients, intimate partners, employers, and police. In addition, support of sex workers in addressing these workplace issues would also empower them to report and intervene more often in cases of human trafficking and exploitation. Such an approach, we suggest, is particularly relevant for sex workers like Nonhle Zulu who might not know the official definitions of trafficking, but are trying to improve their working conditions, and better understand the anti-trafficking policies that tend to impact their lives.

Ntokozo Yingwana is a researcher and PhD candidate with the African Centre for Migration and Society (ACMS) at the University of Witwatersrand. Yingwana’s main passion lies in gender, sexuality, and sex worker rights activism in Africa. She has worked for the Sex Workers Education and Advocacy Taskforce (SWEAT) and currently serves on its board. She also consults for the African Sex Worker Alliance (ASWA), and the Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP). Email: ntokozo.yingwana@wits.ac.za.

Dr Rebecca Walker is a postdoctoral research fellow with the African Centre for Migration and Society (ACMS) at the University of Witwatersrand. Walker completed her PhD in Social Anthropology at the University of Edinburgh. Her work deals largely with issues of gender, migration, sex work, and motherhood. Her recent studies have explored the experiences of migrant and refugee mothers in inner-city Johannesburg, migrant mothers who sell sex, and the impact of South Africa’s Trafficking in Persons Act on the vulnerabilities faced by migrant sex workers. Email: bexjwalker@gmail.com.

Alex Etchart is the co-founder of the award-winning repeat-sellout-show Sex Worker’s Opera. Etchart’s roles include producer, director, and composer, as well as delivering bridge-building workshops to women’s, LGBTQ+, and migrant groups and organisations on bulding alliances with sex workers. Etchart is a second-generation Uruguayan refugee in London, using music, theatre and dance to support grassroots movements in taking queer, feminist, decolonial action. They studied Social Anthropology and Ethnomusicology at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Community Music at Goldsmiths, University of London. Email: alex@sexworkersopera.com.

[1] C Gould, ‘Moral Panic, Human Trafficking and the 2010 Soccer World Cup’, Agenda, vol. 24, no. 85, 2010, pp. 31-44, https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2010.9676321; C Gould and N Fick, Selling Sex in Cape Town: Sex work and human trafficking in a South African city, Institute for Security Studies, Pretoria/Tshwane, 2008; D Peters and Z Wasserman, “What Happened to the Evidence?” - A Critical Analysis of the South African Law Reform Commission’s Report on ‘Adult Prostitution (Project 107)’ and Law Reform Options for South Africa, Asijiki Coalition, Cape Town, 2018.

[2] Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women, Sex Workers Organising for Change: Self-representation, community mobilisation, and working conditions, GAATW, Bangkok, 2018.

[3] Republic of South Africa (RSA), Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act, No. 32, 2007.

[4] See, for example: M Richter and W Delva, ‘Maybe it will be better once this World Cup has passed’ - Research findings regarding the impact of the 2010 Soccer World Cup on Sex Work in South Africa, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Pretoria, 2011.

[5] J Coetzee, R Jewkes and G E Gray, ‘Cross-Sectional Study of Female Sex Workers in Soweto, South Africa: Factors associated with HIV infection’, Public Library Of Science (PloS) ONE, vol. 12, no. 10, 2017, pp. 1-21, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184775; R Walker and E Oliveira, ‘Contested Spaces: Exploring the intersections of migration, sex work and trafficking in South Africa’, Graduate Journal of Social Sciences, vol. 11, issue 2, 2015, pp. 129-153; L Connelly, L Jarvis-King and G Ahearne, ‘Editorial—Blurred Lines: The contested nature of sex work in a changing social landscape’, Graduate Journal of Social Science, vol. 11, issue 2, 2015, pp. 4-20; F Scorgie, et al., ‘“We are Despised in the Hospitals”: Sex workers’ experiences of accessing health care in four African countries’, Culture, Health & Sexuality, vol. 15, no. 4, 2013, pp. 450- 465, https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.763187; Gould and Fick, 2008; A Scheibe et al., ‘Sex Work and South Africa’s Health System: Addressing the needs of the underserved’, South African Health Review, vol. 19, 2016, pp. 165–178; M Richter and J Vearey, ‘Migration and Sex Work in South Africa: Key concerns for gender and health’ in J Gideon (ed.), Gender and Health Handbook, Edward Elgar Publishing, London, 2016, pp. 268-282; D Evans and R Walker, The Policing of Sex Work in South Africa: A research report on the human rights challenges across two South African Provinces, Sonke Gender Justice and SWEAT, 2018.

[6] Hands Off!, Sex Work & Violence in Southern Africa. A participatory research in Botswana, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe, Aidsfonds, Amsterdam, 2018; T Sanders, Sex Work: A risky business, Cullompton, Willan Publishing, London, 2005.

[7] Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS), UNAIDS guidance note on HIV and sex work, UNAIDS, Geneva, 2012.

[8] M Richter et al., ‘Characteristics, Sexual Behaviour and Risk Factors of Female, Male and Transgender Sex Workers in South Africa’, South African Medical Journal, vol. 103, no. 4, 2013, pp. 246–51, https://doi.org/10.7196/samj.6170.

[9] Walker and Oliveira, 2016.

[10] Amnesty International, Explanatory Note on Amnesty International’s Policy on State Obligations to Respect, Protect and Fulfil the Human Rights of Sex Workers (POL 30/4062/2016), AI, London, 2017; Open Society Foundations, 10 Reasons to Decriminalize Sex Work, OSF, New York, n.d.; International HIV/AIDS Alliance, Policy Position on Decriminalisation and HIV, IHAA, East Sussex, 2015.

[11] Justice and Constitutional Development Republic of South Africa, Media Briefing: Report on sexual offences: Adult prostitution, retrieved 1 June 2017, http://www.justice.gov.za/m_statements/2017/20170526-SALRC-Report.html.

[12] Peters and Z Wasserman, 2018.

[13] Z Wasserman, ‘South African Law Reform Commission’s Report on “Adult Prostitution” - Overview and Critiques’, Asijiki Coalition Annual General Meeting Presentation on 14 September 2018.

[14] C Gould, M Richter, and I Palmary, ‘Of Nigerians, Albinos, Satanists, and Anecdotes’, South African Crime Quarterly, no. 32, 2010, pp. 37–44, https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2010/v0i32a883; R Walker and T Galvin, ‘Labels, Victims and Insecurity: An exploration of the lived realities of migrant women who sell sex in South Africa’, Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 277–292; R Walker and A Hüncke, ‘Sex Work, Human Trafficking and Complex Realities in South Africa’, Trafficking, Smuggling and Human Labour in Southern Africa (Special Issue), vol. 2, no. 2, 2016, pp. 127–140.

[15] S Manoek, ‘Stop Harassing Us! Tackle Real Crime!’: A report on human rights violations by police against sex workers in South Africa, Women’s Legal Centre, 2012, retrieved 2 July 2017, http://www.sweat.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Stop-Harrasing-Us-Tackle-Real-Crime.pdf; D Evans and R Walker, 2018; E Bonthuys, ‘The 2010 Football World Cup and the Regulation of Sex Work in South Africa’, Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 38, no. 1, 2012, pp. 12-29; Walker and Oliveira, 2015.

[16] For more details on the methodology, see GAATW, 2018, pp. 210–211.

[17] C Van Onselen, New Babylon and New Nineveh: Studies in the social and economic history of the Witwatersrand, 1886–1914, London and New York City, 1982, reprinted Johannesburg, 2001; H Trotter, Sugar Girls & Seamen: A journey into the world of dockside prostitution in South Africa, Jacana Media, Auckland Park, 2008.

[18] N Yingwana, ‘South Africa’, in GAATW, 2018, p. 216.

[19] Four participants from the Johannesburg focus group shared cases that could explicitly be identified as human trafficking. Ibid., pp. 216–217, 221–222.

[20] Ibid., pp. 221–222.

[21] N Sonandi and M Remba, Report on the Sex Workers’ Anti-trafficking Research Symposium, Cape Town, 2018.

[22] Yingwana, pp. 216–217.

[23] J Busza, ‘Sex Work and Migration: The dangers of oversimplification—A case study of Vietnamese women in Cambodia’, Health and Human Rights, vol. 7, no. 2, 2004, pp. 231–249, https://doi.org/10.2307/4065357.

[24] Yingwana, 2018, p. 218.

[25] R Weitzer, ‘Sex Trafficking and the Sex Industry: The need for evidence-based theory and legislation’, Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, vol. 101, issue 4, 2013, pp. 1337–1370.

[26] Ibid., p. 1338.

[27] H Shamir, ‘A Labor Paradigm for Human Trafficking’, UCLA Law Review, vol. 60, no. 1, 2012, pp. 76–136.

[28] This Venn diagram was developed in personal conversations with Alex Etchart, who is the co-director of the Sex Worker’s Opera, and one of the co-authors of this paper.

[29] The Sex Worker’s Opera is a sex worker-led multimedia project, which presents over 100 stories from 18 countries across six continents on stage, in workshops with NGOs, and online. The project is ongoing, with stories still being added as text, video or audio interviews from individuals and grassroots groups from places such as Argentina, India, Taiwan or Ukraine. Retrieved 14 January 2019, http://www.sexworkersopera.com/about.

[30] English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP), Statement: The Soho raids – what really happened, ECP, January 2014, retrieved 14 January 2019, http://prostitutescollective.net/2014/01/the-soho-raids-what-really-happened.

[31] R King, N Mai, and M Dalipaj, Exploding the Migration Myths. Analysis and recommendations for the European Union, the UK and Albania, Oxfam and Fabian Society, London, 2003; see also the SEXHUM: Migration, Sex Work and Trafficking project, retrieved 14 January 2019, https://sexualhumanitarianism.wordpress.com.

[32] Walker and Oliveira, 2015, pp. 129–153.

[33] See, for example: J Boyle, ‘Death in a cold, strange land’, BBC News, 24 March 2006, retrieved 14 January 2019, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/4582470.stm#map.

[34] See, for example: J O’Connell Davidson, ‘Troubling Freedom: Migration, debt, and modern slavery’, Migration Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 2013, pp. 176–195, https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mns002.

[35] UN General Assembly, Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, 15 November 2000, Art. 3.

[36] Sonandi and Remba.

[37] Busza.

[38] Alex Etchart.