ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

Kiril Sharapov

This article provides a summary of research undertaken to investigate public awareness and understanding of human trafficking in Great Britain, Hungary and Ukraine. Responding to the lack of reliable empirical data on this issue, the research relies on representative national opinion surveys to assess the extent of public awareness of what constitutes human trafficking, the sources of knowledge underpinning this awareness, and respondents’ attitudes towards key dimensions of human trafficking as embedded in international and respective national legal and policy frameworks and discourses. Conceptually, this article reinforces recent calls for policy and media paradigm shifts from understanding human trafficking as a phenomenon of crime and victimhood, to, above all, a human rights concern linked to the broader issues of sustainable development and social justice. Methodologically, the study highlights the role of opinion surveys as a measure of effectiveness and impact of anti-trafficking awareness campaigns. In practical terms, the article presents a set of data which can be useful for policy-makers, anti-trafficking activists, and national media in designing impactful awareness-raising campaigns and interventions.

Keywords: public opinion, anti-trafficking policies, awareness-raising, news media, trafficking in human beings, survey research

Please cite this article as: K Sharapov, ‘Public Understanding of Trafficking in Human Beings in Great Britain, Hungary and Ukraine’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 13, 2019, pp. 30-49, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201219133

In arguing that the monitoring of public understanding of human trafficking can be one of the elements of the ‘universal gold standard for anti-THB initiatives’,[1] this paper provides a summary of research undertaken to investigate the extent of public awareness and understanding of human trafficking in Great Britain, Hungary and Ukraine. It suggests that longitudinal representative surveys of national opinion or surveys of specific demographic groups could provide a methodologically reliable measure of gaps in public understanding of human trafficking, which can be used to inform the design of awareness-raising campaigns. In addition, in case of a longitudinal and, depending on the study design, comparative nature of such research, it could be used to evaluate the efficiency and impact of awareness-raising activities, highlighting areas for potential legal and policy interventions.

The paper begins by setting out the context which has allowed for continuing calls for more anti-trafficking awareness without providing any means to assess the need for such campaigns, their content, and, finally, their efficiency. It then describes the methodology used to gain a snapshot of public understanding of human trafficking in three European countries/territories: Great Britain, Hungary and Ukraine.[2] It then presents the outcomes of these representative surveys, highlighting gaps in knowledge among the general public in these countries. It concludes with a series of recommendations that can inform future research, policy and practitioner agendas in the field of anti-trafficking.

In 2015, the European Commission released a report on the content and impact of prevention initiatives on trafficking in human beings in Europe.[3] The study was carried out by Deloitte,[4] on behalf of the European Commission, to ‘systematically evaluate [among other activities] the impact of anti‐trafficking prevention initiatives, in particular awareness‐raising activities (including online activities)’.[5] About 85 per cent of the projects assessed in the study dealt with information and awareness-raising measures. The report highlighted significant gaps in the evaluation of effectiveness of such initiatives, suggesting that projects tended to focus on monitoring rather than the evaluation of impacts. The report noted a lack of ‘universal gold standard for anti-THB initiatives to be implemented in a particularly effective and impactful fashion’[6] resulting in a situation where, for example, ‘…mass media campaigns may increase people’s awareness regarding the problems of THB, but this may not necessarily be translated into changes in people’s daily and cultural behaviours that eventually lead them to boycotting labour and services produced through exploitation, or to actively monitor the incidence of THB in their environments’.[7]

One of the problematic assumptions embedded in the statement above and, perhaps, reflecting the report’s own assertion about the lack of a ‘universal gold standard’, is that boycotting labour and services produced with the involvement of exploited labour would necessarily lead to lesser reliance on such labour without altering structural relations of labour exploitation within the context of increasingly globalised neoliberal economies.

In December 2018, the European Commission issued its second report on the progress made in the fight against trafficking in human beings.[8] In setting out a range of measures to counter ‘the culture of impunity and [to prevent] trafficking in human beings’, the report allocated a specific role to members of the general public by suggesting that increased awareness would ‘target demand for services exacted from victims of trafficking’, and emphasising the need for ‘campaigns or educational programmes aimed at discouraging demand for sexual exploitation’.[9] Despite identifying awareness-raising actions as a priority, the report provided no insights into what type of awareness it alluded to: awareness aimed at preventing unsuspecting citizens from becoming victims (within the context where almost half of the reported victims [44 per cent] were EU citizens[10]); awareness aimed at enabling members of the general public to recognise and report suspected cases of trafficking or labour exploitation; or awareness aimed at turning the general public into ‘responsible’ consumer-citizens questioning the human (and environmental) cost of goods and services and demanding corrective actions from governments and businesses. Furthermore, the underlying implication of calling for more awareness-raising is that the current levels of public awareness are not achieving what they should (even though the ultimate goals of awareness-raising are rarely specified) and, therefore, more awareness-raising is needed. However, little is known and revealed about the extent to which the general public is aware of what human trafficking is; whether awareness translates into any meaningful action; and who is shaping public understanding and knowledge of human trafficking.

The study reviewed in this paper was carried out in 2013-2014—in the run up to the reporting period of the second European Commission report (covering the period 2015-2016). It relied on representative surveys of public opinion in Great Britain, Hungary and Ukraine which remains one of the trafficking routes from Eastern into Central and Western Europe. A key conclusion of this study is that although the majority of citizens are generally aware of what human trafficking is and consider it to be a problem of crime (rather than a broader human rights concern), they do not consider it to be a problem that affects them directly. Although a minority, a significant number of survey respondents in these three countries could not explain what human trafficking was. This finding raises a question about the extent to which such a lack of knowledge may put citizens at risk of becoming victims of human trafficking, or render them unable to identify and report victims as they go about their daily lives.

Despite a number of methodological and conceptual limitations, including a relatively limited ‘shelf-life’ of opinion polls, the survey analysis presented in this paper responds to the following two broad questions: (a) What does the general public know about human trafficking, and what are the underlying attitudes? and, importantly, (b) What is missing from the public understanding of trafficking as a problem?

Opinion polling, as Stromback notes, remains the ‘best methodology yet invented to investigate public opinion’.[11] This is despite the contested methodological issues of sampling, question ambiguity, wording and context, and a more fundamental question about the extent to which general population surveys provide a valid representation of the public’s views. Yet, opinion polls still hold a significant potential to reveal ‘essentially rational collective preferences’[12] formed through a complex interaction of public, media and policy agendas. In understanding citizens as products of their surrounding political culture, the two key questions that the study of public opinion may answer are how they—the citizens—think at present, and how, under different conditions, they might think (and act) differently. Within this context, it is generally accepted that having a knowledge and understanding of public opinion as expressed by outcomes of opinion polls is usually ‘…better for democracy than not having it. Good information is better than misinformation.’[13]

Social science survey research can never be completely free of bias, subjectivity or even methodological errors. However, survey errors can be minimised within the constraints of cost, time and ethics. This research relied on the ‘survey research triangle’, proposed by Weisberg[14] to address the following concerns: (a) survey errors, including the issues of measurement, nonresponse, sampling and coverage; (b) survey constraints, including costs, time and ethics, and (c) survey effects, including question-related, mode and comparison effects. The issues of measurement, nonresponse, sampling and coverage were, in part, addressed by appointing three experienced market research companies in the case-study countries to undertake face-to-face surveys of representative national samples as part of national omnibus surveys.[15] The survey methodology details for each national sample are provided in the table below. In the analysis that follows, national-level results are presented using national-level weights[16] supplied by survey providers. Time and cost limitations prevented having three national surveys administered by a single market research company. Instead, three national companies were recruited following a competitive bidding process. As a consequence of relying on three different survey providers, the outcome datasets include slightly differing demographic and social classifications, and, despite being representative of national populations (within the established margins of error), they are based on different quota sampling methods and weighting procedures administered by the three national survey providers. These limitations may have affected the outcomes of the subsequent comparative analysis, without diminishing the robustness, validity and representation of the national survey outcomes. The original design of the study made a specific focus on the potential benefits of the national-level rather than comparative-level outcomes for a diversity of actors involved in anti-trafficking prevention initiatives at the national levels.

|

Ukraine |

Hungary |

Great Britain |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Methodology and Date |

Omnibus face-to-face, PAPI (paper-and-pencil interviewing), January 2014 |

Omnibus face-to-face, PAPI (paper-and-pencil interviewing), December 2013 |

Omnibus face-to-face, CAPI (computer-assisted personal interviewing), January 2014 |

|

Sample Size |

1,000 representative of national population within the specified age range |

1,000 representative of national population within the specified age range |

1,000 representative of GB population within the specified age range |

|

Sampling |

Multi-stage sample based on random probability approach with respondents selected by the random route technique with the ‘last birthday’ method employed at the end stage of selection |

Multi-stage sample selected with proportional stratification with final respondents selected by random walking sampling |

Multi-stage sample - 125–150 sample points per survey week at the first stage; addresses were randomly selected from the Post Office Address file (PAF); residents were interviewed according to interlocking quotas on gender, working status and presence of children |

|

Age range |

15–59 |

18 and older |

16 and older |

|

Coverage |

Ukraine, national, six regions singled out on a geographic and economic basis |

Hungary, national, eight regions (including Budapest) |

Great Britain, south of the Caledonian Canal |

|

Weighting |

Quota & weight |

By gender, age group, type of settlement and educational level |

By gender, age group, social class and region |

|

Quality control |

4% of completed interviews controlled by face-to-face method and 6% by telephone (100 interviews) |

Multiple techniques, including random visits by regional instructors (10%), postal or by telephone post-survey quality control when required |

10% back check |

|

Company used |

GfK Ukraine, www.gfk.ua |

TARKI, |

UK-based market-research company; name not released for contractual reasons |

|

Representation |

Representative of the national population, age range 15–59, margin of error (95% confidence level) +/- 3.1 percentage points |

Representative of the national population, age range 18+, margin of error (95% confidence level) +/- 3.1 percentage points |

Representative of the national population, age range 16+, margin of error (95% confidence level) +/- 3.1 percentage points |

The questionnaire for the survey was developed in consultations with anti-trafficking activists and scholars; questions were drafted using procedures proposed by Booth, Colomb and Williams[17] and Hader,[18] where the problem was ‘operationalised’ by identifying its key dimensions in the first place. The next step involved collecting a series of statements to describe each of the dimensions, and the transformation of these statements into a series of questions by applying the technique of asking ‘who’, ‘what’, ‘where’, ‘when’, ‘why’, and ‘how’. Each question was then assigned an objective to understand what type of information it was likely to solicit and how this information contributed to the overarching research objective. Unsuitable, duplicate and equivalent statements and questions were eliminated in an iterative manner. The remaining questions were standardised by constructing a scale using the Likert scaling technique with a five-point scale response format. The analysis that follows assumes that all given responses represent a ‘good approximation of the attitude of a respondent under study’.[19] To address a reported tendency where some respondents are likely to answer ‘agree’ to all questions if all of them are positively formulated, about 40% of items in the final questionnaire were negatively formulated in order to reduce response acquiescence.

In addition to the questionnaire design, the issues of conceptual equivalence are particularly relevant within the context of cross-cultural and cross-language research, where word-by-word language equivalence does not always guarantee the equivalence of ideas and concepts. To ensure the equivalence of meaning and measurement between three different versions of the questionnaire (English, as the original ‘source’ questionnaire, Ukrainian and Hungarian) both qualitative and quantitative methods were deployed, including the detailed annotation of the source questionnaire and the iterative back-translation (as advised by Fu and Chu[20]). A multi-stage pre-testing and a piloting process to ensure equivalence at both linguistic and conceptual levels accompanied this process.

The final survey questionnaire included four questions overall. The first question was open-ended; it included no prompts and asked respondents to explain, using their own words, what human trafficking was. The SPSS Text Analytics for Surveys software was used to identify key textual patterns. Each dataset consisted of about a thousand qualitative responses (including ‘do not know/no opinion’ responses). Each response was manually assigned one or several codes pre-extracted by SPSS Text Analytics following a series of iterative readings. Once this process was completed, the identified codes were contextually approximated: for example, ‘violence and abuse’ in one dataset was matched against ‘abuse and coercion’ and ‘force and dependency’ in two other datasets, resulting in a single code applied across all three datasets; the ‘buying and selling of people’ was used as a single term to cover a diversity of semantic references to either the process of selling and/or buying of people; or to the description of crime, i.e. ‘trade in people’ or ‘the sale of people’. Inevitably, a number of semantic nuances may have been lost in the process of standardising responses; however, these were not deemed significant within the context of a comparative multi-language study.

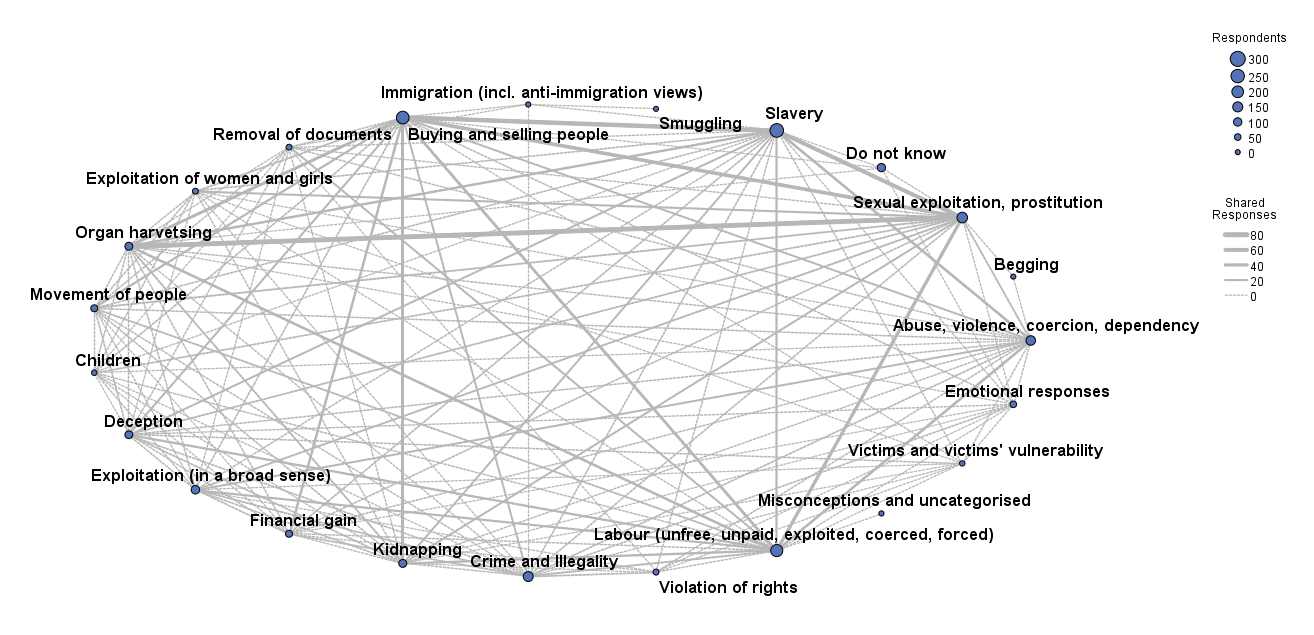

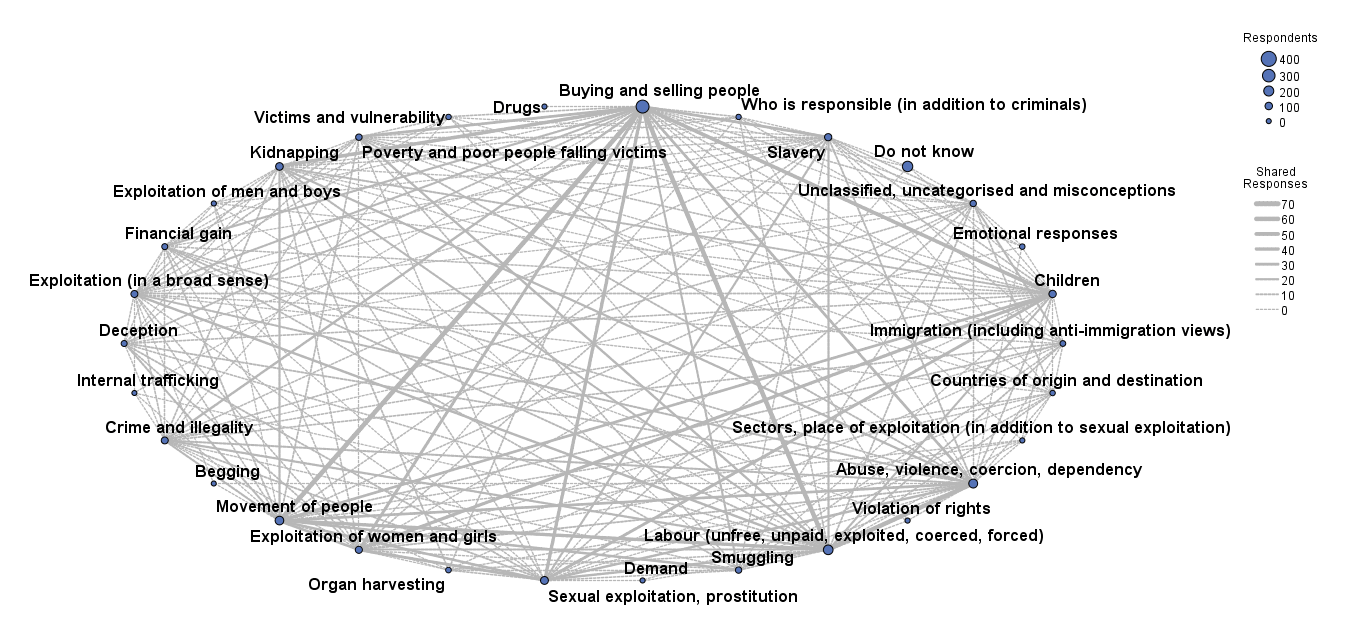

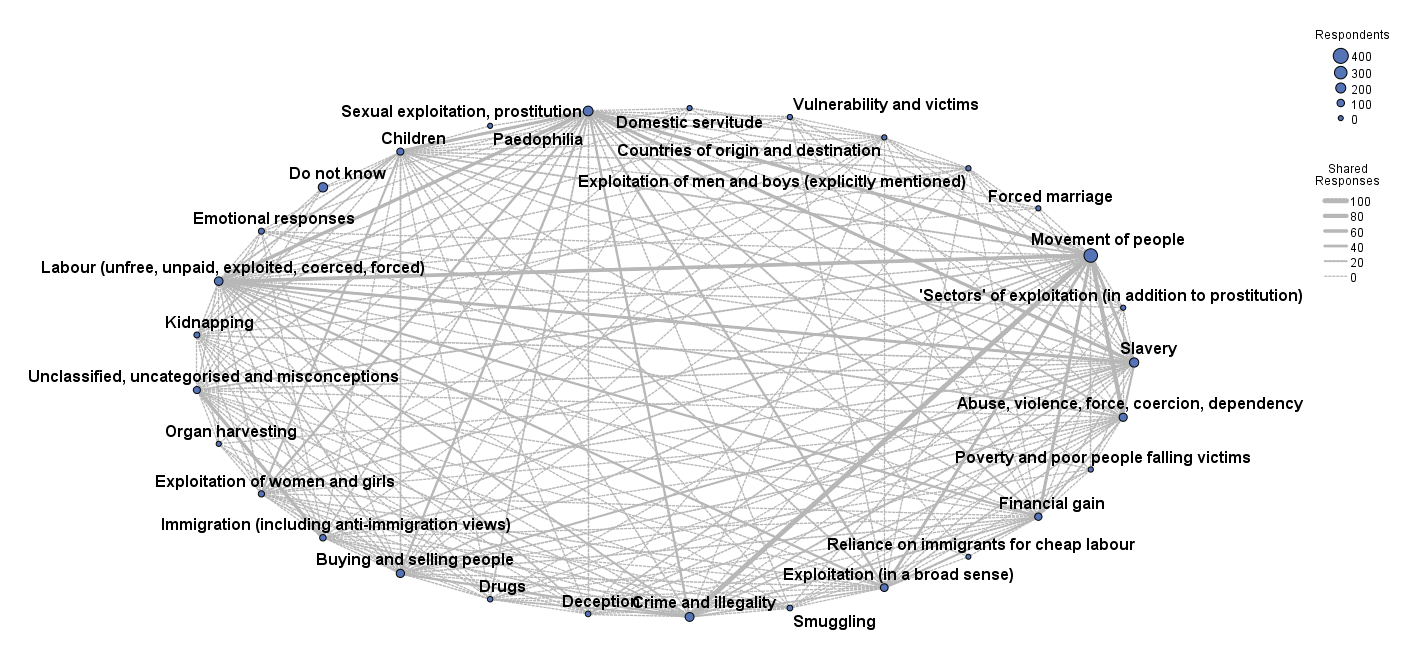

SPSS Text Analytics was also used to generate visual representations of the key categories and of any interrelationships between them, shown in the figures below. Each visual representation consists of a series of dots representing codes, and lines pointing to the existence of an association between the codes; or, in other words, a situation, where an individual response may have been assigned two or more codes. The frequency of codes in the dataset is represented by the size of the dots, which are arranged in a random circular order. The thickness of the connecting lines identifies the strength of the overall relationship between a pair of codes. The analysis of associations was limited to binary associations for key codes only: for example, the association between ‘Slavery’ and ‘Immigration’ is noted (a binary association of codes), however no analysis of the association between ‘Immigration’, ‘Slavery’ and ‘Crime’ was undertaken.[21] ‘Codes’ and ‘Categories’ are used as technical terms in discussing the methodological aspects of this analysis. In the discussion of outcomes, the word ‘vector’, drawn from Aradau’s work,[22] is used when referring to methodological codes/categories. Aradau, in discussing the politicisation of trafficking as a socially constructed category, applies the concept of ‘vectoring’ to metaphorically describe a force that acts in a certain direction. This article uses the notions of a ‘vector’ and ‘vectoring’ to describe a range of issues or actions interacting in a certain pattern to form an overall aggregate picture of how human trafficking is understood by the general public in the three case-study countries.

The second question was closed and asked respondents to identify how they learnt what human trafficking was (prior to the interview) and provided a list of potential sources of information. The remaining two questions included a series of statements covering different aspects of human trafficking, asking respondents to indicate whether they agreed or disagreed on a five-point Likert scale (Strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree, do not know). The ‘do not know’ option was included to prevent a situation where respondents were willing to offer opinions that were obscure or fictitious.

Ukraine

In Ukraine, the predominant understanding of human trafficking centres around the issues of slavery, buying and selling of people, and unfree labour. These three vectors characterise about 70% of responses. The general pattern suggests that the general public understands human trafficking as a process that involves buying and selling of people into slavery for the purposes of labour and sexual exploitation. Anti-trafficking legal and policy frameworks in Ukraine[23] refer to ‘the sale of people’ or ‘trade in people’ to describe trafficking in human beings as understood by the UN Trafficking in Persons Protocol. The terms ‘trafficking in human beings’ (no equivalent term in Ukrainian) or ‘slavery’ (equivalent term in Ukrainian: ‘rabstvo’) do not appear in any of the official documents. The decision by the Ukrainian government to avoid using ‘slavery’ as a policy/legal term is significant given that the references to ‘slavery’ and ‘slaves’ became commonplace in the reporting of human trafficking by Ukrainian news media. In Ukraine, newspaper stories about ‘slavery’ and sexual and labour ‘slaves’ are not only commonplace but also specific in providing often sensationalist and highly individualised stories of Ukrainian ‘slaves’ subjected to forced labour and sexual exploitation abroad.

Another finding, which highlights the role of mass media in influencing public perceptions, is a relatively high share of respondents (9%) identifying organ harvesting as a vector of human trafficking in Ukraine. Organ harvesting remained a low priority within the context of the anti-trafficking policy and legislation in Ukraine at the time of survey research;[24] nevertheless, sensationalist stories about organs cut out of unsuspecting patients by healthcare professionals and sold abroad by criminal groups were regularly featured in the national media.[25] About 21% of Ukrainian respondents associated human trafficking with unfree labour; however, no survey respondents referred to the phenomenon of ‘zarobitchanstvo’, which relates to the post-Soviet labour market changes in Ukraine, including a large-scale labour migration of Ukrainian citizens abroad and internally in search of employment.

About 16% of Ukrainian respondents associated human trafficking with sexual exploitation and prostitution. About half of these respondents also mentioned organ harvesting reflecting the sensationalisation of ‘sexual slavery’ and ‘human organs trade’ by Ukrainian news media. About 15% of respondents described trafficking as crime or illegal activity. This was followed by 13% of respondents expressing their concern about violence, abuse and violation involved in trafficking.

Overall, public understanding of trafficking in Ukraine can be described as a ‘patchwork’ of views, with slavery, buying and selling of people, and unfree labour dominating the overall pattern. Links between various vectors remain weak, with little or no significant associations to allow for the identification of a more complex pattern of views and opinions. This, however, may be due to the specific research methodology, where respondents had limited time to express their views and no prompts were used to encourage further discussion. About 10% of Ukrainian responses were coded as ‘Do not know’.

Hungary

There was no single predominant public view of human trafficking associated with the Hungarian sample; a range of vectors included: buying and selling of people (31%), unfree labour (18%), abuse, violence, coercion and dependency (16%), and movement of people (15%). Together, these vectors characterise about 80% of responses. The general response pattern suggests that trafficking involves coercion, violence and abuse to sell and buy people, transport and exploit them. The other two significant aspects were sexual exploitation and prostitution (12%) as well as kidnapping (11%). In 2013, the Hungarian government published its 2013-2016 anti-trafficking strategy.[26] Vulnerable women trafficked for sexual exploitation by organised criminals, victim identification, assistance and support are key priorities of the Hungarian government as well as of national NGOs, whilst combatting criminal groups or individual traffickers is passed on to the national law enforcement. As a policy and legal concern, human trafficking has been identified as having little relevance to the everyday lives of Hungarian citizens. Within this context, almost a quarter of Hungarian respondents were unable to explain what human trafficking was, or recognise it as a problem for the country, or as a problem which may affect them directly.

Great Britain

About 34% of respondents in Great Britain associated human trafficking with the movement of people without explicitly mentioning immigration. This was followed by sexual exploitation and prostitution (19%), slavery (17%), crime and illegality (16%). These four vectors characterised 86% of responses. These responses, as the association analysis indicates, were interrelated: for example, 28% of respondents identifying ‘movement of people’ as a distinguishing feature of human trafficking also mentioned crime and illegality, while 16% mentioned sexual exploitation and prostitution, and 14% slavery. Out of 154 respondents who described trafficking as associated with crime and criminality, 62% identified it as related to the movement of people, and 20% to sexual exploitation and prostitution. The overall understanding of trafficking as involving people—or ‘slaves’—being moved for labour exploitation and prostitution by criminals reflects a specific representation of trafficking by the UK Government as a problem of crime and ‘illegal immigration’ that threaten the security of the UK borders.[27] At the time the survey was conducted, human trafficking had already been framed by some of the NGO campaigns as ‘modern slavery’, a framing that was subsequently adopted in 2015 with the passing of the Modern Slavery Act. About 18% of respondents were unable to explain what human trafficking was.

In comparing the three national sets of responses, a number of findings need to be highlighted. In all three countries, public opinion can be described as a patchwork of views mirroring the fact that national and international policy-makers, activists, practitioners and scholars identify human trafficking as a matter of concern for very different reasons. In Ukraine and Hungary, human trafficking is predominantly understood as the process of the selling and buying of people and labour exploitation. This may reflect the fact that both countries remain, predominantly, source and transit countries for women and girls subjected to trafficking for sexual exploitation, and for men and women trafficked for labour exploitation.[28] In Great Britain, human trafficking is understood as the process of movement (of people), and sexual exploitation and prostitution, reflecting the overall UK government approach towards trafficking as a subset of ‘illegal’ migration, and the dominant association of human trafficking with sexual exploitation and prostitution in UK media reporting.[29] In terms of the general levels of knowledge of human trafficking, the highest level of awareness was among respondents in Ukraine (with only 10% of respondents not being able to provide an explanation), followed by Great Britain (18%), and Hungary (22%). Further research is required to explore the consequences that such gaps in knowledge may have for respondents belonging to various socio-demographic groups; the extent to which public service announcements and human trafficking awareness campaigns respond to the specific demographic and socio-economic characteristics of their target audiences; and whether such campaigns, overall, remain the most effective approach to improving public awareness.[30]

In order to understand how respondents gained their knowledge of human trafficking, they were asked to identify sources of information that informed their knowledge before the day of the interview. The answers were recorded as given, without any further prompts or follow-up questions. Identifying key sources of information and public knowledge of human trafficking could be one of the first steps in assessing the impact of anti-trafficking awareness-raising campaigns—something that despite the proliferation of awareness-raising campaigns is still missing. Table 2 provides a comparative overview of what sources of information were mentioned by respondents. It is based on the data drawn from samples subjected to a sample-reduction procedure to allow for the selection and comparison of responses falling within the age range of 18-59 shared across the three samples. The final number of respondents for each sample decreased from 1,000 to 693 (N=693) resulting in the increased margin of error of 3.72 at the standard 95% confidence level. The table includes items which recorded a minimum of 10% of responses in at least one of the samples.

|

Sources of information |

Ukraine, % of respondents |

Hungary, % of respondents |

Great Britain, % of respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Someone I know told me about it |

7.3 |

14.4 |

4.4 |

|

Watched a news programme on TV |

53.4 |

80.4 |

59.8 |

|

Watched a documentary on TV |

44.8 |

26.3 |

38.7 |

|

Watched a film on TV |

30.5 |

18.1 |

16.1 |

|

Listened to a programme on the radio |

8.9 |

25.6 |

20.0 |

|

Read an article in a newspaper |

17.7 |

35.6 |

40.0 |

|

Read about it on the internet |

22.7 |

23.0 |

14.0 |

A number of implications can be drawn from the results above. The role of various media sources, in particular TV programmes, in influencing public understanding of what human trafficking is should not be underestimated. The impact of the stereotypical media imagery of human trafficking and ‘simplistic solutions [embedded in such imagery] to complex issues without challenging the structural and causal factors of inequality’[31] has been investigated by both practitioners and scholars in a number of geographical contexts and, also, in relation to specific media forms.[32] Within this context, the key task for anti-trafficking activists, practitioners and scholars is to start, or continue, working in partnership with specific media outlets to ensure that any media reporting of human trafficking (and related categories of human smuggling and irregular migration) engages with more complex social meanings of exploitation and agency,[33] rather than relying on ‘convenient labels’[34] of individualised ‘criminals’ and ‘their victims’. Further context-specific research is required to investigate which media outlets could be relied upon in reaching out to members of the general public who may not be fully aware of what human trafficking and its associated risks are.

The two remaining survey questions asked respondents to indicate the extent of their agreement or disagreement with a series of statements, organised around five broad topics: who the victims of human trafficking were; whether human trafficking was a problem at the national level and whether it affected respondents individually; who the criminals and victims were; how victims could be assisted; and how trafficking could be prevented. The analysis of responses revealed a number of cross-national differences: for some questions, the results were broadly similar; for others, public opinion remains markedly distinct, with responses from Hungary standing out for the worse, from the UK for the better, and those from Ukraine often in the middle. The summary below covers some of the headline findings (categorised into ‘No gap in knowledge’ and ‘Gap in knowledge’ on the basis of the 50+% majority), which indicate the extent of respondents’ agreement with a pre-set statement. Rather than providing any endorsements of a particular viewpoint on what human trafficking is and how it could be addressed, these findings highlight a series of significant gaps in public knowledge and understanding of human trafficking (identified in square brackets below).

Anyone, including men, women and children, can be trafficked (93% of respondents in Great Britain and Ukraine agreed, 94% in Hungary) [No gap in knowledge[35]]; however, the majority of victims are women trafficked for sexual exploitation (92% agreed in Ukraine, 91% in Hungary, 70% in Great Britain) [No gap in knowledge[36]];

Most victims come from poor countries (89% in Hungary, 82% in Ukraine, 76% in Great Britain) [Gap in knowledge[37]]; most of them are irregular immigrants looking for work (84% agreed in Ukraine, 80% in Hungary, 56% in Great Britain) [Gap in knowledge[38]];

Human trafficking is a problem in respondents’ countries (77% in Great Britain, 73% in Ukraine, 64% in Hungary) [No gap in knowledge[39]] but it does not affect respondents directly (81% in Hungary, 75% in Ukraine, 72% in Great Britain) [Gap in knowledge[40]];

Respondents do not normally think that goods or services they purchase may have been produced with the involvement of forced labour (79% Ukraine and Hungary, 67% in Great Britain) [Gap in knowledge[41]] but declared their preparedness to pay more to ensure goods and services are produced without labour exploitation (73% in Great Britain, 53% in Hungary, 48% in Ukraine) [No gap in knowledge[42]] and to boycott companies that rely on exploited labour (86% in Great Britain, 72% in Hungary, 65% in Ukraine) [No gap in knowledge[43]].

Organised criminals bear the main responsibility for human trafficking (90% in Hungary, 86% in Ukraine, and 81% Great Britain) [Gap in knowledge[44]];

Victims of trafficking need to be provided with assistance (91% in Hungary, 89% in Ukraine, 87% in Great Britain) [No gap in knowledge]; victims who crossed international borders need to be deported after a short recovery period (82% in Hungary, 78% in Ukraine, 47% in Great Britain) [Gap in knowledge] or allowed to stay if they face danger back home (78% in Hungary, 76% in Great Britain, 69% in Ukraine) [No gap in knowledge[45]].

There is a need for tougher border controls to stop victims from crossing borders (90% in Ukraine, 89% in Hungary, 84% in Great Britain) [Gap in knowledge[46]] and tougher law enforcement to tackle criminals (94% in Ukraine and Hungary, 90% in Great Britain) [No gap in knowledge[47]]; all European countries should criminalise the purchase of sex (92% in Hungary, 91% in Ukraine, 72% in Great Britain) [Gap in knowledge[48]], and countries of victims’ origin should do more to increase standards of living as a way of managing economic migration (92% in Ukraine and Hungary, 81% in Great Britain) [No gap in knowledge[49]].

Companies relying on trafficked labour need to be identified and prosecuted (93% in Great Britain, 92% in Ukraine and Hungary) [No gap in knowledge]; companies need to ensure that their workers are not exploited and paid a living wage even if this may result in higher consumer prices (91% in Great Britain, 89% in Hungary, 88% in Ukraine) [No gap in knowledge[50]].

More awareness-raising campaigns on human trafficking are required in the media (92% in Ukraine, 91% in Great Britain, 90% in Hungary), on the internet (92% in Ukraine, 89% in Ukraine, 86% in Great Britain) and at schools (93% in Ukraine, 90% in Hungary, 80% in Great Britain) [Neutral[51]].

The time-specific snapshot of public attitudes described above highlights a number of issues that are similar across all three samples. News media, as noted in the previous section, appear to be a key source of information for the general public on the matters related to human trafficking, whilst policy discourses, to a significant degree, set the space in which the construction of human trafficking media ‘truths’ takes place. The outcomes of the study and the existing critical accounts of how human trafficking remains a politicised and increasingly weaponised[52] political construct suggest that these processes allow people to be aware of human trafficking but, at the same time, to craft and maintain a sense of distance from it—an invisible yet facilitated and managed process of social production of ignorance and manufactured denial.[53] It appears that the ‘information deficit model’, increasingly relied upon by anti-trafficking stakeholders in calling for more awareness campaigns, may be irrelevant in a situation where the majority of respondents are aware of human trafficking, its exploitative contexts, declare their preparedness to act ‘ethically’, and are supportive of measures to hold businesses and corporations to account for unfree labour. At the same time, most respondents continue to think of human trafficking as a phenomenon of unabated crime, ‘illegal’ immigration and sexual abuse (and call for greater policing and border control as well as for criminalising the purchase of sex), and, therefore, as something that remains removed from their everyday lives. Within this context, repeated calls for more ‘awareness-raising’[54] fail to recognise the already existing public knowledge (and significant gaps within it), or to tailor awareness-raising campaigns to address the lack of knowledge of human trafficking among certain demographic groups.

The ‘snapshot’ of public understanding of human trafficking in the three case-study countries highlights its complexity, where a number of ‘vectors’ intersect in a complex pattern of individual responses to form three distinct national-level patterns of opinion. Although the majority of these vectors can be found in all three national samples, these national-level patterns remain distinctly unique. They appear to reflect the dominant representations of human trafficking embedded within the context of national anti-trafficking policies and media reporting. The findings raise a series of questions about the timeliness, content and objectives of many anti-trafficking initiatives. The majority of such initiatives, reviewed by the European Commission,[55] appear to be based on an assumption that at any point in time and at any geographical location, more people need to know more about human trafficking. Without taking stock of what is already known, and without having a concrete set of achievable and measurable objectives, such initiatives offer little in terms of new ways of thinking about the personal relevance of what is constructed (in policies and the media) to be a remote and personally irrelevant problem.

The study identified that public awareness of human trafficking does differ within specific national contexts and among members of different demographic groups. It means that any future awareness-raising campaigns would only make sense when basic parameters and baseline differences in knowledge and attitudes are known to the campaigners, practitioners and policy-makers. Methodologically, the study also highlighted the role of opinion surveys as a measure of gaps in public understanding of human trafficking. Identifying such gaps, especially if undertaken from a longitudinal perspective, could inform the design of future awareness-raising campaigns, and enable practitioners and activists to gain an evaluation of their efficiency and impact, highlighting areas for potential legal and policy interventions.

One of the key messages emerging from this study is that current levels of public knowledge and understanding of human trafficking need to be improved, both in terms of the reach of such knowledge (i.e. reaching out to people unware of what human trafficking is) and in terms of its content. The latter, however, remains a dilemma that requires an urgent solution regarding the type of knowledge that the general public genuinely needs in order to be able to respond to the hardships and poverty of people—either in other parts of the world or in nearby factories or farms—in such a way that the politics and ethics of encounters with the exploited ‘Other’ are channelled through and framed by the politics of human rights and justice, and (re)produced through the cultural and economic practices of our everyday lives.

Kiril Sharapov is Associate Professor of Applied Social Sciences at Edinburgh Napier University. He received his PhD in Politics from the University of Glasgow, and an MA in Human Rights from the Central European University. Kiril’s research interests include migration and mobility with a particular focus on human rights, trafficking in human beings and ‘modern slavery’, forced migration, free and unfree labour; as well as subjectivity, politics and neoliberalism; and environmental degradation and social divisions. Email: k.sharapov@napier.ac.uk

[1] European Commission, Study on Prevention Initiatives on Trafficking in Human Beings: Final report, Brussels, 2015, p. 7, retrieved 10 April 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/sites/antitrafficking/files/study_on_prevention_initiatives_on_trafficking_in_human_beings_0.pdf. The report uses ‘THB’ as an abbreviation for ‘trafficking in human beings’.

[2] A representative survey reported in this paper included Great Britain, south of the Caledonian Canal, excluding Northern Ireland.

[3] European Commission, Study on Prevention Initiatives.

[4] Deloitte is a global provider of audit and assurance, consulting, financial advisory, risk advisory, tax, and related services. It was mandated by the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Home Affairs to conduct a study on prevention initiatives on trafficking in human beings following an invitation to tender.

[5] Ibid., p. 7.

[6] Ibid., p. 8.

[7] Ibid., p. 30.

[8] European Commission, Second Report on the Progress Made in the Fight Against Trafficking in Human Beings (2018), Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-security/20181204_com-2018-777-report_en.pdf.

[9] Ibid., p. 8.

[10] Ibid., p. 2.

[11] J Stromback, ‘The Media and Their Use of Opinion Polls: Reflecting and shaping public opinion’ in C Holtz-Bacha and J Stromback (eds.), Opinion Polls and the Media: Reflecting and shaping public opinion, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2012, pp. 1–22.

[12] V Price, ‘The Public and Public Opinion in Political Theories’ in W Donsbach and M W Traugott (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Public Opinion Research, Sage, London, 2008, p. 21.

[13] H Taylor, ‘The Value of Polls in Promoting Good Government and Democracy’ in J Manza, F L Cook and B I Page (eds.), Navigating Public Opinion: Polls, policy and the future of American democracy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2002, p. 316.

[14] H F Weisberg, ‘The Methodological Strengths and Weaknesses of Survey Research’ in W Donsbach and M W Traugott (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Public Opinion Research, Sage, London, 2008, pp. 223–231.

[15] An omnibus survey is a shared cost, multi-client approach to survey research, where a market research company carries out a survey on behalf of commissioning organisations. As a result, each omnibus survey consists of several ‘blocks’ of questions to collect the data on a wide variety of subjects during the same interview.

[16] See an explanatory note provided by the UK Data Service (available: at https://www.ukdataservice.ac.uk/using-survey-data/data-analysis/survey-weights) for further information on survey weights, weighting variables and weighted data.

[17] Cited in K A Rasinski, ‘Designing Reliable and Valid Questionnaires’ in W Donsbach and M W Traugott (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Public Opinion Research, Sage, London, 2008, p. 367.

[18] M Hader, ‘The Use of Scales in Surveys’ in W Donsbach and M W Traugott (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Public Opinion Research, Sage, London, 2008, p. 389.

[19] Hader, p. 390.

[20] Y-C Fu and Y-H Chu, ‘Different Survey Modes and International Comparisons’ in W Donsbach and M W Traugott (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Public Opinion Research, Sage, London, 2008, p. 286.

[21] For further details on associations within individual datasets refer to the research report available at: https://cps.ceu.edu/sites/cps.ceu.edu/files/cps-working-paper-upkat-public-knowledge-and-attitudes-towards-thb-2014.pdf.

[22] C Aradau, Rethinking Trafficking in Women: Politics out of security, Palgrave, Basingstoke 2008.

[23] See Parliament of Ukraine, The Law of Ukraine on Combating [the process of] the Sale of People, 20 September 2011, and Government of Ukraine, State Targeted Social Programme on Combatting [the process of] the Sale of People] up to 2015, 21 March 2012.

[24] Organ transplants in Ukraine are regulated by a separate law, see Parliament of Ukraine, the Law of Ukraine on Transplantation of Organs and Other Anatomical Materials, 16 July 1999.

[25] See, for example, an article (author unknown) distributed widely on Russian-speaking online media sources: ‘Na Ukraine protsvetaet chernaya transplantologiya (Black Market in Human Organs is Flourishing in Ukraine)’, Rambler, 28 April 2018, https://news.rambler.ru/world/39734307-na-ukraine-protsvetaet-chernaya-transplantologiya.

[26] Government of Hungary, 4-Year Plan Document Related to the Directive against Human Trafficking and the European Strategy towards the Eradication of Trafficking in Human Beings and Replacing the National Strategy against Human Trafficking 2008–2012, 2013 [on file with the author].

[27] K Sharapov, ‘“Traffickers and Their Victims”: Anti-trafficking policy in the United Kingdom’, Critical Sociology, vol. 43, no. 1, 2015, pp. 91–111, https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920515598562.

[28] For further details/country profiles, see https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/member-states.

[29] Sharapov, 2015.

[30] See a series of contributions under the theme of ‘The Wastefulness of Human Trafficking Awareness Campaigns’ arguing that awareness-raising as such and as an isolated activity does not change anything and may, if badly performed, have counterproductive or even harmful impacts: E Shih and J Quirk, ‘Introduction: Do the hidden costs outweigh the practical benefits of human trafficking awareness campaigns?’, Open Democracy, 11 January 2017, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/beyond-trafficking-and-slavery/introduction-do-hidden-costs-outweigh-practical-benefits-of-huma.

[31] R Andrijasevic and N Mai, ‘Editorial: Trafficking (in) representations: Understanding the recurring appeal of victimhood and slavery in neoliberal times’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 7, 2016, pp. 1–10, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121771.

[32] See, for example, issue 7 of Anti-Trafficking Review, ‘Trafficking Representations’, http://www.antitraffickingreview.org/index.php/atrjournal/issue/view/15.

[33] For a more detailed discussion of human trafficking representations in the media and on the internet reviewed through the lens off agnotology, a study of how ignorance is produced and becomes productive, see: J Mendel and K Sharapov, ‘Human Trafficking and Online Networks: Policy, analysis, and ignorance’, Antipode, issue 48, 2016, pp. 665–684, https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12213.

[34] R Zetter, ‘Labelling Refugees: Forming and transforming a bureaucratic identity’, Journal of Refugee Studies, vol. 4, issue 1, 1991, pp. 39–62, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/4.1.39.

[35] See: UNODC, Global Report on Trafficking in Persons, UNODC, Vienna, 2018, p. 10, retrieved 10 April 2019, https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/2018/GLOTiP_2018_BOOK_web_small.pdf.

[36] Ibid., p. 10.

[37] Ibid., p. 53.

[38] See: IOM, Global Migration Indicators 2018, UN Migration, Geneva, 2018, retrieved 10 April 2019, https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/global_migration_indicators_2018.pdf.

[39] UNODC.

[40] The impact of human trafficking and associated criminal activities on the overall population in both sending and receiving countries is acknowledged; however, it remains poorly theorised, including the issues of crime control by national governments as well as the suggested yet contested (for failing to address structural factors) consumers’ involvement (direct and indirect) in creating and sustaining demand for exploitative (including trafficked) labour.

[41] G LeBaron and N Howard, ‘Forced Labour in the Global Economy’ in G LeBaron and N Howard (eds.), Forced Labour in the Global Economy. Beyond Trafficking and Slavery Short Course | Volume 2, Open Democracy, 2015, p. 8.

[42] Given the scale of exploitative labour within the context of the global economy, ‘demand for cheap products or services that are always and quickly available have led to adjustments in some of the industries where trafficked persons tend to work’. See UN.GIFT, The Vienna Forum to fight Human Trafficking 13–15 February 2008, Austria Center Vienna, Background Paper, 2008, p. 4, https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/2008/BP010SupplyManagementILO.pdf. However, as Cyrus and Vogel note, if low price is taken as indicator of potential labour exploitation, ‘a higher price does not necessarily signal fairer or exploitation-free labour conditions’. See N Cyrus and D Vogel, ‘Evaluation as Knowledge Generator and Project Improver. Learning from demand-side campaigns against trafficking in human beings’, Contemporary Readings in Law and Social Justice, vol. 10, no. 1, 2018, pp. 57–93.

[43] See: AA Aronowitz, ‘Regulating Business Involvement in Labor Exploitation and Human Trafficking’, Journal of Labor and Society, vol. 22, 2019, pp. 145–164, https://doi.org/10.1111/wusa.12372.

[44] See: G Vermeulen, Y Van Damme and W De Bondt, ‘Perceived Involvement of “Organised Crime” in Human Trafficking and Smuggling’, Revue Internationale de Droit Pénal, vol. 81, no. 1, 2010, pp. 247–273, https://doi.org/10.3917/ridp.811.0247.

[45] For critical discussion of ‘deserving’ victims of human trafficking and the ‘masses that remain undeserving of rights and freedoms’ see J O’Connell Davidson, ‘New Slavery, Old Binaries: Human trafficking and the borders of “freedom”’, Global Networks, vol. 10, 2010, pp. 244–261, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2010.00284.x. For discussion of assistance and support offered to victims of human trafficking in the UK, see K Roberts, ‘Life after Trafficking: A gap in UK’s Modern Slavery efforts’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 10, 2018, pp. 164–168, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.2012181012.

[46] For a discussion on the role of states in depriving migrants of their freedom see: J O’Connell Davidson, ‘De-canting “Trafficking in Human Beings”, Re-centring the State’, International Spectator, vol. 51, no. 1, 2016, pp. 58–73, https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2016.1121685.

[47] See: SH Krieg, ‘Trafficking in Human Beings: The EU approach between border control, law enforcement and human rights’, European Law Journal, vol. 15, 2009, pp. 775–790, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0386.2009.00490.x.

[48] See: A Lepp and B Gerasimov, ‘Editorial: Gains and Challenges in the Global Movement for Sex Workers’ Rights’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 12, 2019, pp. 1–13, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201219121.

[49] See: S Castles, ‘Why Migration Policies Fail’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, vol. 27, no. 2, 2004, pp. 205–227, https://doi.org/10.1080/0141987042000177306.

[50] See: J Planitzer, ‘Trafficking in Human Beings for the Purpose of Labour Exploitation: Can Obligatory Reporting by Corporations Prevent Trafficking?’, Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights, vol. 34, no. 4, 2016, pp. 318–339, https://doi.org/10.1177/016934411603400404.

[51] See: K Sharapov and J Mendel, ‘Trafficking in Human Beings: Made and cut to measure? Anti-trafficking docufictions and the production of anti-trafficking truths’, Cultural Sociology, vol. 12, issue 4, 2018, pp. 540–560, https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975518788657, and other contributions in the present volume.

[52] See, for example: KD Gleason, CK Baker and A Maynard, ‘Discursive Context and Language as Action: A demonstration using critical discourse analysis to examine discussions about human trafficking in Hawai‘i’, Journal of Community Psychology, vol. 46, 2018, pp. 293–310, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21940.

[53] For further discussion of ignorance and denial in relation to human trafficking, see Mendel and Sharapov, 2016.

[54] See Sharapov and Mendel, 2018, for an overview of how anti-trafficking awareness raising is often achieved through the dramatisation and fictionalisation of human trafficking in the mass media, and without identifying who is being targeted or what the goals of awareness-raising are.

[55] European Commission, Study on Prevention Initiatives.