ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

Jen Birks and Alison Gardner

Past studies have indicated that the British public consider human trafficking to be remote from their personal experiences. However, an increase in local press reporting, alongside the emergence of locally co-ordinated anti-modern slavery campaigns, is starting to encourage communities to recognise the potential for modern slavery and human trafficking to exist in their own localities. In this article, we examine how local media and campaigns may be influencing public perceptions of modern slavery and human trafficking. We draw upon a content analysis of local newspapers to review how reports represent cases of modern slavery, and use focus group discussions to understand how local coverage modifies—and sometimes reinforces—existing views. We find that, whilst our participants were often surprised to learn that cases of modern slavery and human trafficking had been identified in their area, other stereotypical associations remained entrenched, such as a presumed connection between modern slavery and irregular migration. We also noted a reluctance to report potential cases, especially from those most sympathetic to potential victims, linked to concerns about adequacy of support for survivors and negative consequences relating to immigration. These concerns suggest that the UK’s ‘hostile environment’ to migrants may be undermining the effectiveness of ‘spot the signs’ campaigns, by discouraging individuals from reporting.

Keywords: human trafficking, modern slavery, local, media, campaigns, perceptions

Please cite this article as: J Birks and A Gardner, ‘Introducing the Slave Next Door’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 13, 2019, pp. 66-81, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201219135

Evidence on public perceptions of human trafficking in the United Kingdom (UK) suggests that the majority of people associate it with illicit and criminal activity at the margins of society; studies agree that around four in five people are familiar with the term, although understandings are varied and partial.[1] Sharapov shows that the strongest associations revolve around the movement of people, sexual exploitation, slavery, and crime and illegality, meaning that survey respondents considered trafficking to be an issue without relevance or proximity to their daily lives. The vast majority (72% in Sharapov’s report[2] and 79% in Dando et al.) report that trafficking does not directly affect them. As Sharapov puts it: ‘human trafficking remains separated from the immediate economic, social or ethical universe of the “normal” person’s life’ with the result that individuals—and societies—tend to ignore structural and societal drivers of the problem such as the demand for cheap goods and services.

Yet, increasingly, local statutory services, media coverage and local awareness campaigns are challenging the idea that such crimes are remote occurrences, by highlighting local cases as part of ‘place-based’ campaigns against modern slavery. This article explores the extent to which more localised representations of modern slavery and human trafficking impact upon that sense of detachment amongst members of the public. We utilise both the terms ‘modern slavery’ and ‘human trafficking’ as both are prevalent (and used interchangeably) in the UK media and public discourses, which in recent years have been influenced by the framing of the 2015 Modern Slavery Act and accompanying government policy.[3] Whilst we understand that the value of the term ‘modern slavery’ is contested and there is variance in social and legal interpretations,[4] our focus on the UK means that it is essential to engage with this terminology.

Following the adoption of the 2015 Modern Slavery Act, police and criminal justice responses to modern slavery have come under scrutiny,[5] and an increase in attention to the problem by local police forces has resulted in rising numbers of arrests and increased referrals to the National Referral Mechanism (NRM), the government’s support framework for victims.[6] This has, in turn, prompted an uptick in coverage from local press and media, with one East Midlands newspaper publishing more than seven times as many stories on modern slavery and trafficking in 2017 than in 2016 (see below for further analysis).

In addition, previous research by Gardner et al. identified 42 examples of local multi-agency anti-modern slavery partnerships in the UK, most of which list training and awareness-raising amongst their activities.[7] The UK Home Office also invested in an awareness campaign in 2014 (‘Modern Slavery is closer than you think’) and local areas have extended this work with targeted campaigns such as Manchester’s ‘Would you?’ (recognise the signs of modern slavery) campaign, or Nottingham’s pledge to become a ‘slavery-free’ city and community.[8] This local action is underpinned by academic literature highlighting examples of exploitation within the UK[9] and encouraging us to recognise the possible existence of the ‘slave next door’.[10] Visual representations, such as Amy Romer’s photographic series ‘The Dark Figure’, also serve to highlight the mundane character of UK sites associated with identified cases of modern slavery and human trafficking, featuring images of industrial estates, suburban streets, and rural settings which resonate in many local contexts.[11]

But to what degree does this local framing contribute to challenging perceptions about the remote-ness of modern slavery, and moving the conversation towards a more nuanced understanding of the problem, as one which is connected to our everyday lives?[12] One academic critique of media representation and awareness-raising campaigns is that they tend to reinforce a narrow view of modern slavery—often associated with sexual exploitation.[13] However, these analyses of press and media stories on modern slavery and human trafficking generally focus on national rather than local-level press coverage.[14]

By contrast, this study combines a media content analysis and focus-group discussions to look at representations of modern slavery and human trafficking in the local media of the UK’s East Midlands region, and the reception of those media representations by members of the public. It examines the degree to which certain myths and misconceptions are maintained at local level, and how the nature of local reporting maintains or challenges those myths. Whilst confirming findings that members of the public are confused about recognising modern slavery, it suggests that local campaigns can help frame a broader understanding of the issue.[15] It also notes that even amongst those sympathetic to potential victims, discomfort with immigration policy and a fear of increasing vulnerability may be discouraging some members of the public from acting as the ‘eyes and ears’[16] to ‘spot the signs’ of modern slavery.

Previous research has suggested that TV and newspapers are significant sources of information on human trafficking for UK audiences.[17] Whilst local press circulations have been falling in recent years, many local papers still retain a presence in community life, and provide a trusted source of local news, in hard copy and online. The UK government has also recognised the significance of local media, recently requiring the BBC to contribute to resourcing local journalism through the Local Democracy Reporting Service.[18]

Local media is important to local anti-trafficking initiatives such as those in Nottingham and Manchester because events and awareness-raising are more likely to attain media coverage locally than nationally. Furthermore, there can be political implications to the impact of local campaigns, as it is often local, rather than national, politicians who allocate relevant front-line resources to training, enforcement, awareness-raising and survivor support services. As a recent police inspectorate report highlighted, an absence of political attention to modern slavery and human trafficking is sometimes attributed to the perceptions that the local electorate does not see the issue as a problem,[19] so if local media contribute to raising public concern about modern slavery, resources will potentially follow.

Research has shown development in the way that modern slavery and human trafficking are represented in press coverage over time. Both Marchionni[20] and Sanford et al.[21] find a tendency for early reports to be dominated by government perspectives and a focus on individual stories of victims, with a resulting over-emphasis on sexual exploitation and trafficking of women and children, as compared to individuals whose experiences of exploitation do not fit the mould of an ‘ideal’ or ‘legitimate’ victim.[22] The popular press typically uses simplified victim framing, with victims frequently characterised as passive and vulnerable women, who have been deceived (rather than more complex stories that explore individual agency and choice).[23] However, later studies describe a more critical framing of the issue, which emerged as legislation matured and the issue became more widely understood.[24] These studies found an increase in debates on why trafficking occurs and discussions of appropriate strategies for intervention, including a greater critique of law and policy.

Although this trajectory suggests that media framing of trafficking and modern slavery is becoming more nuanced as time goes on, there are some key issues for transferability of lessons to the local level. As Sanford et al. point out, journalists who regularly cover the same area or topic (‘beat reporting’) tend to be desk-based and more reliant on press releases and publicity events[25] than the elite national press, which can devote resources to longer investigative and analytical studies. In Sanford’s view, beat reporting makes greater use of ‘official’ sources of information such as policy documents, and is less likely to offer critical perspectives on government policy.[26] In the context of resource-challenged local media in the UK, this is a pattern we might realistically expect to observe in local press reports.

Another concern about media representations of modern slavery is that they tend to reproduce and reinforce existing myths about modern slavery and human trafficking, which persist in society.[27] Andrijasevic and Mai argue that trafficking representations should not be seen as ‘free-floating’ but ‘embedded within narrative tropes and discursive constructions about gender, sexuality, race and class that are culturally, geopolitically and historically specific’.[28] Examples of common assumptions include the conflation of human trafficking and people smuggling; a belief that it does not happen in developed nations; that it is usually associated with sex work or irregular migration; and that an element of consent or payment means that trafficking has not occurred.[29] Sharapov’s research shows clear associations in public perception between trafficking and people movement, sexual exploitation, and illegality.[30] In order for local media to create a less remote narrative of ‘the slave next door’, it must therefore challenge, rather than underpin, such myths.

This article draws upon ongoing exploratory research in the East Midlands region of the UK to understand whether local place-based initiatives on modern slavery and human trafficking are influencing local media reporting and public perceptions. The East Midlands was interesting partly because of its internal contrasts in anti-modern slavery campaign activity. Derbyshire had been an early actor on the modern slavery agenda, being one of the first counties in the UK to establish a multi-agency approach to awareness-raising, victim identification and response. Nottinghamshire had also established a partnership in late 2016, which promoted its work through a public commitment to a ‘slavery-free community’. Other parts of the region had little or no multi-agency work when we started the research. We therefore conducted an analysis of news reporting over a two-year period from January 2016 to December 2017 to understand whether local campaigns were influencing press coverage.

The sample comprised 148 articles returned in a Nexis database search on ‘modern slavery’ and on ‘human trafficking’ in five local newspapers, excluding passing references. The main city or county newspaper for each of the main counties in the East Midlands was selected.[31] All articles were imported into NVivo, where news sources and themes were coded to determine what aspects of modern slavery and human trafficking were highlighted and which groups in society were driving that framing.

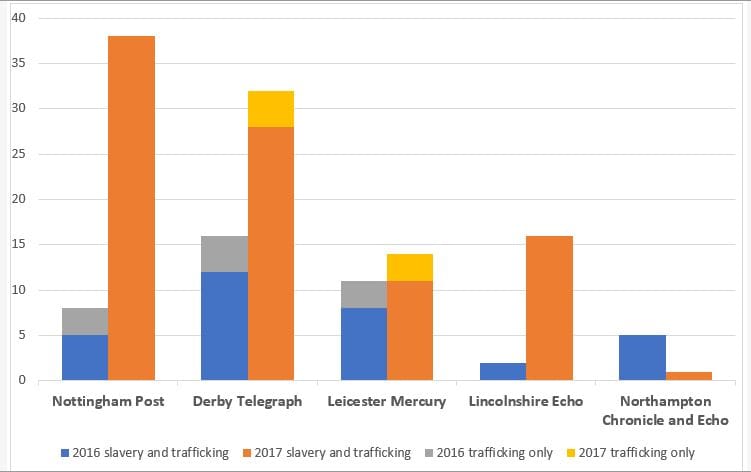

The sample reflects a general growth in coverage of the issue of modern slavery in the East Midlands press between 2016 and 2017 (see Figure 1 below). In part, this can be explained by an increase in detection efforts by police forces following the introduction of the Modern Slavery Act in 2015, but the impact has been uneven across the region. The Nottingham Post and Derby Telegraph lead the region in the amount of reporting on modern slavery and have registered the greatest year-on-year increases in coverage other than the Lincolnshire Echo, which had started from a very low base.

Focus groups were then conducted as a means to understand whether different aspects of press coverage confirmed or challenged attitudes and shared meanings. The intention of this qualitative approach was not to produce results that could be generalised to a population, but rather to test whether local reports confirmed or challenged attitudes to trafficking that we expected our groups to exhibit, based on the literature.[32] Participants were first asked about their existing understanding of the issue and their associations with it, as well as the sources of those impressions. They were then shown selected media reporting of the issue, one news report with a crime and enforcement angle, an editorial demonising the perpetrators of modern slavery as ‘human parasites’, and a longer piece that included material on public responsibilities and a personal account from a survivor. We were then able to see how participants processed new information that might contradict prior assumptions, as well as identify limitations with the media reporting in terms of confusion and unanswered questions.

Three focus groups were conducted, with 17 participants in total, gender balanced and all resident in Nottingham. We wanted to test how groups with differing levels of familiarity with modern slavery and human trafficking responded to the reporting. The first group was recruited through Nottingham Citizens, the local branch of Citizens UK, which has had some involvement with anti-modern slavery campaigning and therefore represents an older and a more engaged public. There were also further participants at this group recruited through the Call for Participants online tool. As a whole, this group was more diverse in ethnicity than the other groups, and four participants were born overseas (in Europe, Southeast Asia, the Arab peninsula and North Africa). It became clear in the first stage of the focus group that some participants (involved with the Church and a local refugee charity) were more familiar with the concept than the others, so the group was split in two (more familiar FG1a, mainly from Nottingham Citizens, and less familiar FG1b, mainly from Call for Participants). Focus Groups 2 and 3 were entirely white British. FG2, comprised of students, was recruited through internal advertising within the university. Finally, to identify a less-engaged (not self-selecting) working-age group outside higher-education, we recruited FG3 from a group of participants that knew each other from a local climbing centre, recognising that group cohesion is important to exploring difficult and sensitive topics.[33]

The content analysis showed that the terms ‘modern slavery’ and ‘human trafficking’ both featured in press reports, but the former is gradually replacing the latter as time moves on. Where a definition was offered in the reports, both trafficking and modern slavery were frequently associated with the issue of migration, as well as criminality. However, whilst human trafficking was conflated with people smuggling (in three articles in the Derby Telegraph), modern slavery was more likely to be framed in terms of forced labour, with less emphasis on immigration offences. Furthermore, there were also examples of modern slavery being presented as a social justice issue, especially in the areas where there had been campaigning activity. There was a sixfold increase in the volume of reporting on anti-modern slavery initiatives in 2017 that kept pace with the overall growth in coverage, although the proportion focused on business responsibilities had fallen.

In 2016, modern slavery was largely raised in passing as one of the new challenges for police forces to tackle in the context of limited resources; whereas in 2017, there was a dramatic increase in specific cases (from under a tenth of overall volume to over half), and a shift from arrests (down from almost half of crime-focused volume to 15.5%) to court reporting (up from 1.9% to 52.4%). Interestingly, despite being one of the first newspapers to pick up the issue of modern slavery in the abstract, the Derby Telegraph was slow to frame specific arrests and court cases in these terms, describing two modern slavery cases in terms of the specific trafficking offences (‘conspiracy to arrange travel with the view to exploitation’).

The most marked outcome of the increase in reporting of modern slavery cases was an increase in human interest angles. Human interest news stories are often associated with sensationalist reporting, and there was some evidence of discourses vilifying the perpetrators with shocking details of their lavish lifestyles in contrast with the poor conditions in which victims were kept. However, these kinds of news stories can also convey the significance of the issue to audiences and give a voice to those affected.[34] In the press sample, just under a quarter of human interest coverage drew on survivors’ own accounts (compared to a fifth from police and legal sources), including a woman who had set up a charity supporting fellow survivors (in the Nottingham Post), and a British man who had been trafficked within the UK when sleeping rough in London (in the Lincolnshire Echo). The majority of the ‘victim’s plight’ framing came from eyewitnesses, largely from police interviews and court reporting. Neighbours’ reactions were particularly prominent in the Derby Telegraph (44.4% of human interest, compared to 8.5% on average across the five newspapers), and did pick up the question of why they had not reported their concerns to the police.

The shift toward court reporting also led to a shift in the types of cases that were specified in coverage. In 2016, police sources dominated and their definitions of modern slavery would include sexual exploitation, but, when court reporting began to drive the agenda, the big cases involved manual labour in agriculture, construction and the warehouse of a high street retailer. Sexual exploitation therefore went from being mentioned in 71.3% of the volume on types of modern slavery in 2016 to just 9.6% in 2017; conversely, manual labour more than doubled in proportion, from 31.6% to 69%. Interestingly, sex work was the only kind of labour that appeared in articles that referred to human trafficking but not modern slavery.

Education and awareness angles declined slightly as a proportion of all coverage, but the volume nevertheless increased significantly (from 1,407 to 5,471 words of content in total across the reporting period). In the newspapers with less overall attention to modern slavery, approaches differed. In the Lincolnshire Echo there was a focus on the definition and extent of modern slavery, but nothing on the public’s role and responsibilities in tackling the problem. Conversely, the Northampton Chronicle & Echo did not define modern slavery, though it did highlight the public’s responsibility to recognise the ‘signs of modern slavery’ in nail bars in one article on a specific campaign. Only the Nottingham Post and Derby Telegraph, however, specified in any detail what those signs were.

Furthermore, only the Derby Telegraph and Leicester Mercury gave significant attention to the responsibilities of businesses as employers. The Derby Telegraph quoted Derby’s police commander at length, warning businesses that they risk arrests if they do not demonstrate ‘due diligence’ to ensure that workers have not been trafficked and are not being controlled. Both newspapers reported a local campaign to persuade businesses to sign up to the Athens Ethical Principles.[35] Whilst the principles themselves do not mention ‘modern slavery’, the term was included in the framing of the articles.

Focus group participants varied in their familiarity with the issue of modern slavery, but most had a broad sense of what it involved, although they found it difficult to define where the boundaries lay between modern slavery and other forms of labour exploitation. For example, participants raised sweatshop labour practices in China (Dante, FG1b) and Bangladesh (Sally, FG2), and other exploitative practices in the UK such as unpaid overtime (Ryan, FG3). In two cases, participants questioned these associations by identifying coercion as the distinguishing feature (Diana, FG1a, Maria, FG3). This suggested some confusion related to the more figurative uses of the term ‘slavery’, supporting the aforementioned critiques on the term’s definition and application.

In line with the myths and misconceptions discussed above, participants in all three focus groups immediately associated modern slavery with trafficking for sexual exploitation and forced prostitution, although a surprisingly wide range of types of forced labour were also spontaneously mentioned, including in domestic work and in the construction industry. Most of the groups with lower familiarity assumed that it was something that occurred mostly or wholly elsewhere in countries with poor labour regulations, and where people might have few other options, even if they were not held against their will. They were surprised to learn from the media stimulus material that it not only occurred in the UK, but in the local area.

When participants were aware of cases in the UK, they associated it with ‘trafficking’, which they defined as moving people illegally (Ryan and Anne, FG3) and explicitly conflated it with people smuggling, especially in relation to the recent ‘migration crisis’ from conflict zones such as Libya (Marigold, FG1a). In response to the news items, they were able to readjust their perceptions to some extent in light of the cases involving EU citizens. However, many participants in all groups were nonetheless reluctant to let go of assumptions that entrapment was usually associated with undocumented migrants without legal rights to work in the UK, commenting that victims could not go to the police because they might be deported (Tony, FG1b, William, FG2, Maria, FG3).

Whilst this conflation with people smuggling reflects the dominant myths and associations described above, the most common assumption expressed in our focus groups was that exploited individuals might be consenting to exploitation on the basis that it was preferable to conditions in their country of origin, that ‘they’re so desperate to leave their own country that they’re thinking “well, this is much better than what I get in Lithuania” so they won’t, they won’t want to complain perhaps’ (Shirley, FG1b; also Calum, FG2, and Ryan, FG3). This was persistently understood as a willing choice.

‘If you think about America in the very past, those people didn’t have a choice, they were forced into it, whereas modern day slavery, actually these people might be, err, willing to do it because even though it’s that bad, it’s still better than what they have at home’. (Dante, FG1b)

The concern most often expressed by participants from all the focus groups was that by reporting their suspicions they could actually make matters worse for that individual by getting them deported, because ‘no matter how badly paid or treated, it’s better than what they might get in their home country’ (Calum, FG3), or by making them homeless since ‘even in slavery they had somewhere to stay’ (Anne, FG3). Indeed, some in FG1a recognised that those most affected by exploitation believed the police to be corrupt, and considered their choice not to report rational. This group expressed a strong preference for measures that empowered individuals to report their exploitation themselves over any surveillance role.

Most participants agreed that, in any case, the ‘signs’ listed in the newspaper article were unhelpfully broad. None would have felt confident to raise concerns on the basis of lots of apparently unrelated people living in one house (common to large houses locally rented as Houses of Multiple Occupancy [HMOs][36]) or looking unkempt with long hair (Jo: ‘That could be half of Nottingham’, Ryan: ‘that could be me’, FG3). William worried that ‘I’d feel like I was being a bit discriminatory in a way’ to assume someone speaking another language at a car wash was a ‘slave’. On the other hand, Diana (FG1a) identified assumptions about how Eastern Europeans choose to live as themselves discriminatory, when neighbours failed to raise the alarm about ‘a dozen Polish men living in this small house and being taken off every morning’ because they think ‘that’s just the way these people live.’

Many were surprised to learn that people could be forced to work for legitimate businesses like farms and warehouses, rather than directly for organised crime. Participants were particularly frustrated that one of the companies implicated in employing slave labour via agencies was an ethical egg brand that charges a higher price on the basis of animal welfare (Maria, FG3) and wanted to know how they could shop responsibly.

Whilst most did not spontaneously mention the responsibility of employers to ensure that workers were not exploited, when it was raised, focus group participants agreed that businesses should be more engaged in pro-active measures to reduce vulnerability and promote reporting of exploitation. However, there was some scepticism about the practicality of large corporations keeping a check on all their employees, and little challenge to the widespread use of labour agencies offering casual contracts. There was more agreement about the responsibility of employers to give information about legal rights to support individuals who wished to disclose their own exploitation. Interestingly, the one sector that two of the three groups raised as having some responsibility was not mentioned in the media coverage—namely, that banks could have measures in place to prevent people from forcing others to open accounts and then controlling their finances, though again, there were disagreements on how feasible those measures could be in practice.

It is clear that for many individuals, modern slavery is still a distant issue; despite having a general awareness, most participants were surprised that examples of exploitation could be found so close at hand. In some respects, our research confirmed expectations about local press reporting and reception—there were examples of confusing definitions, conflation of human trafficking and people smuggling, and a heavy emphasis on the criminal justice system and the role of police in addressing the issue. It was, nonetheless, interesting to see that cases framed in terms of ‘modern slavery’ seemed to present a more nuanced perspective on the problem as time progressed, moving from a primary association with sexual exploitation to a broader association including a range of labour abuses.

On the surface, there was a correlation in the East Midlands between areas actively pursuing local anti-modern slavery campaigns and higher levels of local press coverage, but more detailed and longitudinal research is necessary to understand whether this is a causative factor. There was also a suggestion that these areas tended to generate reports offering a thoughtful and challenging presentation of the issue that went beyond the expectations of basic ‘beat reporting’. In the next stage of our research, we intend to look in greater detail at the drivers behind the framing of press releases and media reports, to understand why myths are repeated, as well as what influences coverage to adopt a social justice perspective.

Additionally, whilst some media coverage helped to dispel myths, even those focus group participants who were favourable to police intervention thought the local press focus on court reporting unhelpful. Personal narratives in survivors’ own voices were found to be more revealing, and our participants wanted to know more about how people found themselves in these situations and what happened to them after their stories came to light, showing a willingness to engage beyond a reductive framing of victims’ stories. Our local sample of press and media also included some more detailed stories of survivor empowerment post-exploitation, demonstrating that local press and media can help to amplify these messages. However, such examples remained the exception rather than the rule.

It was also interesting to observe that perceptions were not all about victim-blaming; indeed, our focus groups indicated that people can be sympathetic to trafficked persons and forced labourers, yet still be unwilling to report suspicions to authorities, with those who were most sympathetic also the most distrusting of the police and immigration enforcement. Participants understood that some workers chose to work under exploitative conditions, and respect for that choice, as well as a fear of worsening these people’s situations, were reflected in an unwillingness to act on simplistic ‘spot the signs’ indicators. However, our focus group participants also recognised that making assumptions about others’ willingness to accept exploitation could be discriminatory. They sought increased emphasis on enabling self-reporting, on one hand, and a more convincing picture of victim and survivor support on the other, which might persuade those who were in situations of exploitation (and potential advocates) that reporting would improve their situation. As this article was completed, a new policy was announced that could effectively place a ‘firewall’ or a barrier between police and UK immigration enforcement, citing comments from the head of the Modern Slavery Police Transformation Unit that police connections with communities were being compromised by perceived links to immigration.[37] However, more extensive policy shifts, such as changes to the 2016 Immigration Act, are needed to reshape the existing ‘hostile environment’ for migrants who experience exploitation, and there are no quick fixes to public distrust in the current system.

Finally, our research accords with arguments that there are not yet enough prompts in press and media coverage on how we want society to change to undermine current drivers for modern slavery and human trafficking. Our focus group participants recognised the implications of the UK’s ‘hostile environment’ and the importance of employer responsibility, but these received limited attention in the press. Addressing such issues in local and national press and media campaigns could provide a stronger foundation for de-normalising the conditions which allow exploitation to occur, and greater confidence for those wishing to report abuses.

Jen Birks is Assistant Professor in media in the Department of Cultural, Media and Visual Studies at the University of Nottingham. Her research examines the representation of social justice issues and campaigning in the news, and the role of civil society actors in shaping news framing. She is the author of News and Civil Society (Ashgate, 2014) and Fact-checking Journalism and Political Argumentation (Palgrave, forthcoming 2019), and co-convener of the Political Studies Association Media and Politics Group. Email: Jennifer.Birks@nottingham.ac.uk

Alison Gardner holds a Nottingham Research Fellowship in the School of Sociology and Social Policy at the University of Nottingham. She leads ‘Slavery-Free Communities’, a ground-breaking research programme focussed on developing local, community and place-based responses to modern slavery. She is part of the University of Nottingham’s Rights Lab, which aims to contribute to the UN’s goal of ending modern slavery, human trafficking, child labour and forced labour by 2030. Email: Alison.Gardner@nottingham.ac.uk

[1] K Sharapov, Understanding Public Knowledge and Attitudes towards Trafficking in Human Beings, Part 1, Center for Policy Studies, Central European University, 2014 p. 25, retrieved 8 December 2018, https://cps.ceu.edu/publication/working-papers/up-kat-public-knowledge-attitudes-towards-thb; C J Dando, D Walsh and R Brierley, ‘Perceptions of Psychological Coercion and Human Trafficking in the West Midlands of England: Beginning to know the unknown’, PLOS ONE, vol. 11, no. 5, 2016, pp. 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153263.

[2] K Sharapov, Understanding Public Knowledge and Attitudes towards Trafficking in Human Beings, Part 2, Center for Policy Studies, Central European University, 2015, p. 10, https://cps.ceu.edu/publication/working-papers/up-kat-public-knowledge-attitudes-towards-thb-2.

[3] Under the Modern Slavery Act, modern slavery serves as an umbrella term, encompassing offences of human trafficking as well as slavery, servitude and forced or compulsory labour (Ss1 and 2).

[4] See: J O’Connell Davidson, Modern Slavery: The margins of freedom, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2015, and J Chuang, ‘The Challenges and Perils of Reframing Trafficking as “Modern Day Slavery”’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 5, 2015, pp. 146–149, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121559.

[5] HMICFRS, Stolen Freedom: The policing response to modern slavery and human trafficking, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, London, 2017, https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/wp-content/uploads/stolen-freedom-the-policing-response-to-modern-slavery-and-human-trafficking.pdf.

[6] For statistics on referrals to the NRM, see National Crime Agency, ‘National Referral Mechanism Statistics’, http://www.nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk/publications/national-referral-mechanism-statistics. The number of people entering the NRM rose steadily from 1,746 in 2012–13 to 5,145 in 2017, and 6,993 in 2018, although NRM statistics are not an accurate reflection of the prevalence of modern slavery and human trafficking, as many adults choose not to engage with the system.

[7] A Gardner et al., Collaborating for Freedom: Anti-slavery partnerships in the UK, University of Nottingham, 2017, http://iascmap.nottingham.ac.uk/CollaboratingforFreedom.pdf.

[8] A Gardner, ‘How the home of Robin Hood is trying to free itself of modern slavery’, Independent Online, 2 October 2017, retrieved 8 December 2018, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/how-the-home-of-robin-hood-is-trying-to-free-itself-of-modern-slavery-a8011481.html.

[9] See, for instance: G Craig, ‘Modern Slavery in the UK: The contribution of research’, Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, vol. 22, no. 2, 2014, pp. 159–164, https://doi.org/10.1332/175982714X13971194144714 and H Lewis, P Dwyer, S Hodkinson and L Waite, Precarious Lives, Report funded by the ESRC, University of Leeds and University of Salford, Leeds, 2013, https://precariouslives.files.wordpress.com/2013/07/precarious_lives_main_report_2-7-13.pdf.

[10] K Bales and R Soodalter, The Slave Next Door, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2009.

[11] See The Dark Figure* Mapping modern slavery in Britain, http://www.thedarkfigure.co.uk/the-dark-figure.

[12] Sharapov and Mendel highlight the importance of linking ‘everyday lives, values and social problems’ as a means to stimulate new thinking about the personal relevance of otherwise remote social problems. See K Sharapov and J Mendel, ‘Trafficking in Human Beings: Made and cut to measure? Anti-trafficking docufictions and the production of anti-trafficking truths’, Cultural Sociology, vol. 12, issue 4, 2018, pp. 540–560, https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975518788657. This concept also relates to the broad tradition of the sociology of everyday lives, which explores the connections between macro theory and micro-level practice and behaviours. D Kalekin-Fishman, ‘Sociology of Everyday Life’, Current Sociology Review, vol. 61, no. 5-6, 2013, pp. 714–732, https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392113482112.

[13] See D M Marchionni, ‘International Human Trafficking: An analysis of the US and British press’, International Communication Gazette, vol. 74, no. 2, 2012, pp. 145–158, https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048511432600 and E O’Brien, ‘Human Trafficking Heroes and Villains: Representing the problem in anti-trafficking awareness campaigns’, Social and Legal Studies, vol. 25, no. 2, 2016, pp. 205–224, https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663915593410.

[14] See, for instance: R Sanford, D E Martínez and R Weitzer, ‘Framing Human Trafficking: A content analysis of recent US newspaper articles’, Journal of Human Trafficking, vol. 2, no. 2, 2016, pp. 139–155, https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2015.1107341; A Johnston, B Friedman and M Sobel, ‘Framing an Emerging Issue: How US print and broadcast news media covered sex trafficking, 2008–2012’, Journal of Human Trafficking, vol. 1, no. 3, 2015, pp. 235–254, https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2014.993876; and M Sobel, B Friedman and A Johnston, ‘Sex Trafficking as a News Story: Evolving structure and reporting strategies’, Journal of Human Trafficking, vol. 5, no. 1, 2017, pp. 43–59, https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2017.1401426

[15] Dando et al.

[16] See US Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report 2018, which discusses the role of local communities in anti-trafficking as the ‘eyes, ears and hearts of the places they call home’, p. 2, retrieved 4 April 2019, https://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/2018.

[17] Sharapov, 2014, p. 29.

[18] Information on the service can be found at https://www.bbc.com/lnp/ldrs. Commentary on the role and significance of the scheme was published in 2019 by the Department for Culture Media and Sport as The Cairncross Review: A Sustainable Future for Journalism, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/779882/021919_DCMS_Cairncross_Review_.pdf.

[19] HMICFRS.

[20] Marchionni.

[21] Sanford, Martínez and Weitzer, p. 141.

[22] S Rodríguez-López, ‘(De)Constructing Stereotypes: Media representations, social perceptions, and legal responses to human trafficking’, Journal of Human Trafficking, vol. 4, no. 1, 2018, pp. 61–72, https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2018.1423447.

[23] J Langer, Tabloid Television: Popular journalism and the ‘other news’, Routledge, London and New York, 2006, pp. 79–80.

[24] Johnston, Friedman and Sobel, and Sobel, Friedman and Johnston.

[25] See also B Franklin (ed.), Local Journalism and Local Media: Making the local news, Routledge, London and New York, 2005.

[26] Sanford, Martínez and Weitzer.

[27] See S Hall, ‘Encoding/decoding’, in Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (ed.), Culture, Media, Language: Working papers in cultural studies, 1972–79, Hutchinson, London, 1980, pp. 128–38 and D Morley, The Nationwide Audience, British Film Institute, London, 1980. These studies found that audiences responded differently to the same media content, accepting, negotiating or rejecting the dominant meaning encoded in the text, depending on their prior knowledge, experience, critical skills, class identification and political beliefs.

[28] R Andrijasevic and N Mai, ‘Editorial: Trafficking in Representations: Understanding the recurring appeal of victimhood and slavery in neoliberal times’, Anti Trafficking Review, issue 7, 2016, pp. 1–10, p. 5, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121771.

[29] K C Cunningham and L D Cromer, ‘Attitudes About Human Trafficking: Individual differences related to belief and victim blame’, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, vol. 31, no. 2, 2016, pp. 228–244, https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514555369, and Polaris, ‘Myths & Facts’, n.d., https://humantraffickinghotline.org/what-human-trafficking/myths-misconceptions.

[30] Sharapov, 2014.

[31] The East Midlands comprises Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Northamptonshire and Rutland. Rutland has been excluded from the sample as one of the smallest counties in the UK, lacking a sizeable city or county newspaper.

[32] For a discussion of generalising to theory rather than populations, see R K Yin, Case Study Research Design and Methods, 2nd edition, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, 1994.

[33] T O Nyumba et al., ‘The Use of Focus Group Discussion Methodology’, Methods in Ecology and Evolution, vol. 9, issue 1, 2018, pp. 20–32, https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12860.w.

[34] For example, see J Birks: ‘“Moving Life Stories Tell us Just Why Politics Matters”: Personal narratives in tabloid anti-austerity campaigns,’ Journalism, vol. 18, no. 10, 2017, pp. 1346–1363, https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916671159.

[35] For an explanation of the principles and subsequent implementation guidelines, see End Human Trafficking Now, Luxor Implementation Guidelines to the Athens Ethical Principles: Comprehensive compliance programme for businesses, 2006, https://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/issues_doc/human_rights/Resources/Luxor_Implementation_Guidelines_Ethical_Principles.pdf.

[36] Houses of Multiple Occupancy are residential properties in which bedrooms are rented out under separate tenancy agreements but tenants share common areas such as kitchens and bathrooms.

[37] V Dodd, ‘Police to Stop Passing On Immigration Status of Crime Victims’, The Guardian, 7 December 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/dec/07/police-to-stop-passing-on-immigration-status-of-victims.