ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

Ilse A. Ras and Christiana Gregoriou

This paper focuses on the modern slavery statements of three major UK high street retailers who are known for their relatively pro-active approach to the debate on corporate responsibility for ethical trading. Drawing on our earlier research in relation to metaphors in British newspaper reporting of modern slavery and human trafficking since 2000, we explore the metaphors that recur across the statements these companies have published in 2016, 2017 and 2018. These statements were published in accordance with the UK Modern Slavery Act 2015, which requires all commercial organisations operating in the UK, with a turnover greater than GBP 36 million, to publish an annual statement outlining the work done to assess and address (the risk of) modern slavery in their supply chains. We find that the metaphors used in these statements generally fail to acknowledge the agency of those workers affected by modern slavery and labour exploitation in a broader sense, the potential complicity of the retailers in sustaining an exploitative industry, and the underlying socio-economic factors that leave workers vulnerable to exploitation. We conclude that more needs to be done to account for the causes of modern slavery so that retailers can prevent rather than react to it.

Keywords: Modern Slavery Act, corporate modern slavery statements, metaphor, corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis, labour exploitation

Please cite this article as: I A Ras and C Gregoriou, ‘The Quest to End Modern Slavery: Metaphors in corporate modern slavery statements’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 13, 2019, pp. 100-118, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201219137

The case for examining representations of modern slavery[1] may, by now, be assumed to have been made (and eloquently so).[2] As Andrijasevic and Mai show, such representations:

mobilise stereotypical narratives and visual constructions about sexuality, gender, class and race that end up demarcating people’s entitlement to social mobility and citizenship in increasingly unequal times, […and ] distract the global public from their increasing and shared day-to-day exploitability as workers because of the systematic erosion of labour rights globally. In doing so, they become complicit in the perpetuation of the very social inequalities, hierarchies and conflicts that allow exploitation […] to occur.[3]

In other words, these representations simplify complex issues without challenging the structural and causal factors of inequality that underlie them. In this paper, we address how UK commercial organisations, whose economic and social power exceeds that of NGOs and even many states, communicate their understanding of modern slavery through metaphors in their modern slavery statements (MSSs), since metaphors reflect underlying thought processes, and as such play a central role in the way we structure experiences and conceptualise the society we live in.[4] We also compare the metaphors of these MSSs to the metaphors found in media texts that focused specifically on human trafficking, as described in Gregoriou and Ras, since the guidance produced by civil society organisations, commercial pressures, and media reporting on modern slavery (a term which also covers human trafficking) may have influenced these MSSs, and may have been influenced by these MSSs in turn.[5] The understanding of modern slavery as communicated and negotiated through these documents may be assumed to influence (regulatory) measures taken in response to this issue.

These MSSs are published in compliance with Section 54 (S54) of the UK Modern Slavery Act 2015 (MSA), which calls for companies trading in the UK to publish, annually, a statement outlining what, if anything, they have done to prevent and respond to risks of modern slavery in their supply chains. It must be noted here that the MSA consistently refers to MSSs as ‘modern slavery and human trafficking statements’.[6]

In this article, we use the term ‘modern slavery’ as an umbrella term that includes practices such as ‘chattel slavery, forced labour, debt bondage, serfdom, forced marriage, the trafficking of adults and children, child soldiers, domestic servitude, the severe economic exploitation of children and organ harvesting’, as set out in the MSA.[7] At the same time, we are conscious of the debates around this term, as acknowledged in footnote 1.

The UK government seems to assume that greater transparency leads to greater anti-slavery efforts, and that consumer behaviours and investments are affected by increased transparency or greater anti-slavery efforts. The UK government explicitly hopes that S54 will ‘create a race to the top’ amongst companies in an effort to retain consumer and investor goodwill.[8] However, some suggest that making statements indicating that a given commercial organisation has done very little or nothing to reduce the risk of modern slavery in its supply chains does not carry the necessary repercussions that would create such a race to the top. As New notes, for instance, despite the admission by the US doughnut chain Krispy Kreme, in their statement made under the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act 2010(CTISC), that they do not take any of the expected measures, they met little to no backlash in return. Importantly, they experienced no impact on sales.[9] Indeed, Öberseder, Schlegelmilch and Gruber note that corporate social responsibility is of less concern to many consumers in purchasing decisions than aspects such as price and quality, suggesting that the presence and quality of an MSS will have limited, if any, effect on consumer behaviour.[10] It is, in fact, possible that the understanding of the issue of modern slavery communicated by MSSs and related documents is what stops consumers and investors from prioritising corporate social responsibility (at least in relation to labour practices) as a purchasing factor. Furthermore, an MSS is not necessarily indicative of the amount of efforts actually expended by the company to prevent and respond to modern slavery in its supply chains; as LeBaron and Rühmkorf note, many corporate modern slavery policies tend to be aspirational, rather than truly forcing business decisions by both retailers and the company itself to be made in a manner that improves labour conditions.[11]

The three UK high street retailers whose statements we examined have a history of engagement with debates and reporting practices on modern slavery in supply chains: they are Marks & Spencer (M&S); the John Lewis Partnership (JLP), which includes Waitrose, and Mothercare. These companies are full members of the Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) and have published an MSS every year since the introduction of the MSA.[12] JLP and Mothercare also signed a letter sent in 2014 by the ETI and the British Retail Consortium (BRC) to the Prime Minister, advocating measures beyond voluntary compliance with the MSA, whilst M&S argued independently in favour of S54.[13] Furthermore, M&S and JLP continue to work with the UK government on the topic of modern slavery in supply chains.[14] Lastly, the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC), which examined the MSSs of the then-top 100 companies trading on the London Stock Exchange (also known as the FTSE 100), scoring the coverage of the topics outlined above on a scale of 0-5 on quality and quantity of information and then placing each company in one of ten possible tiers, classified M&S’s 2017 statement as ‘tier nine’.[15]

There are multiple standards against which an MSS can be benchmarked. Firstly, there is the relatively basic question of legal compliance. A legally compliant MSS must, firstly, have been approved by the board of directors, partnership members, or equivalent, where relevant, and subsequently signed by a director or partner; it must also be published on the organisation’s website, with a link to the MSS placed on the homepage.[16] This low threshold can be useful in highlighting those companies unwilling to even make this effort, and is sufficiently low and clear to encourage otherwise averse organisations to at least consider the question of whether their company is linked to the issue of modern slavery and labour exploitation.

A second benchmark is the comprehensiveness of the MSS. Conveniently, the MSA and 2016 Home Office guidance suggest six topics that an MSS ‘may’ cover:

the organisation’s structure, its business and its supply chains;

its policies in relation to slavery and human trafficking;

its due diligence processes in relation to slavery and human trafficking in its business and supply chains;

the parts of its business and supply chains where there is a risk of slavery and human trafficking taking place, and the steps it has taken to assess and manage that risk;

its effectiveness in ensuring that slavery and human trafficking is not taking place in its business or supply chains, measured against such performance indicators as it considers appropriate;

the training about slavery and human trafficking available to its staff.[17]

There is scope for some gradeability of comprehensiveness, in the sense that some statements cover all six topics, and some only one or two. However, even that is a relatively crude measure, and still marks exemplary and sufficiently comprehensive (if barely) as equal.

Other approaches to assessing the quality of an MSS have generally focused on the level of detail offered in these MSSs. Such assessments have been carried out by Ergon and Sancroft and Tussell, albeit for different groups of companies.[18] In November 2018, the ETI launched a framework that indicates exactly what level of detail, per topic, is sufficient. Such detailed guidance is necessary and useful for all stakeholders, seeing that ‘[b]usinesses need to know what to aim at, while investors, parliamentarians and consumers need to know how to hold businesses to account.’[19]

As indicated, in this article, we examine the language used in these MSSs as an additional marker of whether an MSS meets expectations, since even compliant, comprehensive and detailed MSSs may use problematic language. For instance, O’Brien notes that texts on the consumption and retail of goods that may have been manufactured by exploited people tend to avoid discussing the culpability of consumers who, knowingly or negligently, create a demand for such goods.[20] They also tend to avoid discussing the culpability of corporations who, also knowingly or negligently, cater to this demand, exploit employees and workers (who, as opposed to employees, are not directly contracted by the primary retailer), have neglected to stop the exploitation of employees and workers, and/or continue to encourage the exploitation of employees and workers, all for commercial benefit. Instead, these texts tend to cast both consumers and commercial organisations as either ignorant (and thus innocent) or as (potential) heroes simply for doing their due diligence. These texts also tend to encourage continued consumption, albeit now with regard to the labour situation of workers. They tend to steer clear of more radical solutions that scrutinise consumption culture and capitalism. One particularly relevant aspect that O’Brien highlights is the continued focus on the supply chain as the general ‘area’ in which this problem occurs. Suggesting that the issue is in the supply chain, rather than in retail or consumption, creates distance between the issue and the retailer/consumer, ‘insulating us from responsibility’.[21] This also plays into the idea that modern slavery is endemic to the Global South, ‘spreading’ to the Global North. These issues found by O’Brien relate both to the comprehensiveness of such texts (in avoiding particular topics), but also the language used, e.g. agency and word choice.

In this paper, we focus specifically on metaphors; as we note in the next section, metaphors are both indicative of, and affect, the way in which (parts of) society understand(s) particular concepts and events. We hope that our assessment of the metaphors used in the MSSs reviewed in the current study prompts other assessments of the language used in MSSs, and encourages those responsible for the actual writing of these MSSs to continue developing their awareness of their language use.

Metaphors ‘involve understanding one kind of experience in terms of another kind of experience’ by mapping a source domain (where the concept area is drawn from) onto a target domain (where the area is metaphorically applied).[22] To give a classic example, in ‘she attacked his position’ (in a debate or discussion), the argument between the individuals involved is conceptualised along the lines of war, and hence the source domain of the metaphorical wAR is mapped onto the target domain of ARGUMENT, in the metaphor ARGUMENT IS WAR (since, in cognitive linguistic contexts, metaphors are usually presented in small caps). Importantly, ‘the people who get to impose their metaphors on [a] culture get to define what [members of that culture] consider to be true’.[23]

In analysing metaphors in MSSs, we combine a qualitative with a quantitative approach.[24] Our quantitative approach adapts Gabrielatos and Baker’s concept of constant collocates to determine constant semantic domains.[25] Archer, Wilson and Rayson define a semantic domain as ‘group[ing] together word senses that are related by virtue of their being connected at some level of generality with the same mental concept’.[26] In other words, a semantic domain is a group of words that all link to the same topic. Archer et al., for instance, note the semantic domain ‘colours’, which includes words such as red, blue, yellow, but also the semantic domain ‘debt’, which includes words such as bankrupt, overdraft, insolvency.[27] As such, semantic domains generally indicate the topics discussed in the text(s) examined. Furthermore, semantic domains may, according to Koller, Hardie, Rayson and Semino, also be indicative of metaphorical source domains.[28] The next step is then to examine whether these semantic domains are target or source domains. As such, examining which semantic domains are present in a text can be both a starting point for examining how particular topics are (metaphorically) described, and for examining which metaphors are used to describe particular topics. In this study, we examine, in particular, constant semantic domains, which, following Gabrielatos and Baker, occur with a frequency above a pre-defined threshold, in a pre-defined number of constituent parts of the corpus.

The pre-determined threshold was one of statistical significance, i.e. for each semantic domain it was noted whether it occurred with a statistically significant frequency in each constituent part of the corpus. We used Wmatrix to statistically compare the frequencies of semantic domains in each of these nine MSSs (all generated yearly: in 2016, 2017 and 2018) to the frequencies of these same domains in the BNC Written Sampler, which is a one-million-word sample of written British English as collected for the British National Corpus. The significance threshold was set at a log-likelihood-score >15.13, which indicates that a semantic domain occurs at a statistically significantly different frequency in the primary corpus compared to the BNC Written Sampler, at p <.0001.

As we examined three retailers with three MSSs each, we have, in practice, three corpora of three constituent parts each, so there are three lists of constant semantic domains, one for each company. It was pre-determined that a semantic domain must be statistically significant in two out of the three constituent parts of each corpus, i.e. in two out of the three documents for each retailer. We then focused on those constant semantic domains that all three retailers have in common. We used the Metaphor Identification Procedure (MIP) to examine metaphors in all of the sentences in which these common constant semantic domains occurred, focusing on head nouns, verbs, and modifiers.[29] The tables in this paper show, in the column on the left, the constant semantic domains that were examined in further depth, with the right-hand column showing the metaphors found in this in-depth examination.

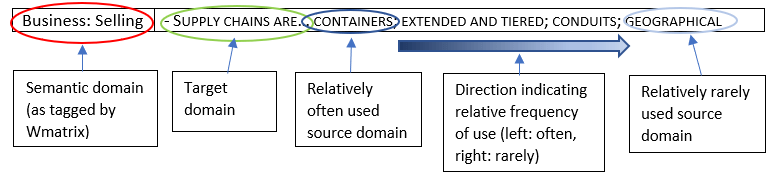

Figure 1 explains how to interpret the tables in the remainder of this paper. The first column of each table shows the semantic domains for which the metaphorical mappings, detailed in the second column, were found. In the second column, metaphors are indicated in the standard form X is Y, Z, whereby X indicates the target domain and Y, Z indicate source domains, listed in order of frequency; source domains that are mentioned first occur with a greater frequency, in relation to the target domain, than source domains that are mentioned later.

The qualitative aspect of our study closely analysed each MSS, also to identify linguistic realisations of prominent metaphors employed in relation to modern slavery, which we were then able to group into types/categories. Though the quantitative and qualitative parts of the analysis were each initially conducted separately and independently by each author, the results of the latter came to ultimately support those of the former, hence the analysis being showcased altogether below.

As indicated in the introduction, the metaphors found were, where possible, linked to those also found in the relevant statutory and civil society guidance, and to metaphors across media (including news and documentaries).[30] As we have discussed before, newspaper writers employ a range of metaphors when reporting on human trafficking, some of which we found to be extended across the whole of our UK newspaper corpus, and some of which were not.[31] Systematic metaphors in the corpus of British newspaper reporting on human trafficking include TRAFFICKING IS A TRADE, TRAFFICKING IS A SPREADING UNWANTED SUBSTANCE and one which CAN BE BROKEN, and RESPONDING TO TRAFFICKING IS WAR. Less prominent (but nevertheless noteworthy) were the TRAFFICKING IS DRAMA/SPECTACLE, the TRAFFICKING IS HIDDEN/NOT VISIBLE, and TRAFFICKING IS ANIMATED AND BEASTLY metaphors.

An important difference between the companies writing these MSSs and the people who are actually affected by the employment policies of these companies and their suppliers relates to their grammatical agency. Companies, factories and mills are, in systemic-functional terms, actors.[32] In these MSSs, companies do, as if they were singular living organisms (e.g. ‘the steps taken by Marks and Spencer Group plc’, ‘M&S […] to dig deeper and think harder in the year ahead’). However, a company’s supposed ability to act as a legal person is a legal fiction, as in reality decisions are made and acts are performed on behalf of the company (as a collective) by people affiliated with that company.

On the other hand, workers are portrayed as having little agency, being primarily acted upon, and as a singular entity, despite each worker, in reality, having a varying capacity for making decisions and performing acts on their own behalf. Table 1 shows the metaphors relating to business, supply chains, workers and workplaces, and in particular shows the overall mappings of workplaces and supply chains as containers and conduits in which workers are placed and through which products flow.

|

Semantic Domains |

Metaphors |

|---|---|

|

Business: Selling |

- Supply chains are… containers; extended and tiered; conduits; geographical |

|

Work and employment: Generally |

- Employment is… a location; precious item |

As indicated in table 1, workers are described as located within the conduit that is the supply chain, as though they were a substance rather than a group of people. They are described as ‘vulnerable’ in 4.56% of the 833 instances of worker*, which is the second-most frequent content collocate to worker* after ‘supply’ (as opposed to function words such as ‘and’, ‘to’, ‘the’ and ‘in’). Furthermore, there is a tendency to talk about ‘protect[ing] workers’ (3.24%), ‘worker engagement’ and ‘engage’ or ‘engaging’ ‘workers’ (5.76%) and ‘worker dialogue’ (1.56%), which leaves the focus on the agent doing the engaging and protecting, rather than on the workers who are being engaged with. There is some acknowledgement that workers have a ‘voice’ (1.68%), ‘health’ (1.20%), and ‘safety’ (1.32%), but these remain items that the retailer takes agency for hearing or improving. These tendencies are very similar to the ones found in relation to the representation of victims of modern slavery more generally, as workers are agentless entities to be rescued and acted upon, rather than agents in their own right, suggesting a general ‘side-lining’ of these workers.[33]

The function of these MSSs is thus not to highlight what is done to assist these workers (which would allow them some agency), but to highlight the actions performed by these companies upon these workers (which focuses solely on the agency of these companies). This is also reflective of power relations, whereby the supplier depends on the end-retailer, and the worker depends on the supplier (and thus, indirectly, the buyer), leaving the retailer as the primary decision-maker and the worker as decision-taker. Anner, Bair and Blasi show that it is retailers’ ability to find new suppliers when existing suppliers, for any reason, become less desirable that drives the exploitative labour conditions of workers in the fashion industry, as it stops workers from being able to demand better labour conditions, out of fear of losing the work altogether.[34] Their proposed response is for both suppliers and retailers to be made not just jointly responsible, but jointly liable, for securing and improving the labour conditions of workers in these supply chains, as agreed with representatives of the workers.[35] The focus, in these MSSs, on the actions taken by these companies does suggest an acceptance of (some) responsibility for improving labour conditions, which seems to generally be taken as meaning the termination of contracts to force improvements, but, perhaps more positively, also as working directly with suppliers to enable suppliers to make these improvements. It is unlikely that suppliers and buyers both will be held liable for improving these conditions until workers have the opportunity to exercise their agency.

Table 2 shows the metaphors relating to modern slavery/a lack of power, as well as some pertinent aspects of modern slavery, such as the risk thereof, and recruitment processes; it also shows the metaphors that relate to responses to modern slavery, such as ‘helping’ and ‘investigating’.

|

Semantic Domains |

Metaphors |

|---|---|

|

No power |

Modern slavery... is an opponent; is visible; is knowable; has a size; is trackable; is a contaminant; is an unwanted substance; is a journey target; is a recipient of communication; is reparable; has a level; is a strategic target; is a substance; is a weapon; is a container; is a disease |

|

Danger |

The risk of modern slavery… has a size; has a level; is geographical; is visible; is a recipient of communication; is an opponent |

|

Work and employment: Generally |

- Recruitment fees are… unwanted substances - Modern slavery is… an unwanted substance - Working conditions are... an opponent - Dealing with this issue is… theatre |

|

Helping |

- Helping is… building |

|

Investigate, examine, test, search |

- Information is... a geographical area; a substance/structure with gaps; a guide; a basis/stepping-stone; a tool; tracks; a transferable item |

|

Wanted |

- Parties are… guides |

|

Business: Selling |

- Retailers are… leading on this journey |

As shown in table 2, one conceptualisation of modern slavery is as an object or substance that can be made visible (but is implied to be, as of yet, hidden or unknown). This is the systematic metaphor of modern slavery is a substance that can be made visible that we also found in newspaper writing.[36] The companies refer to this ‘hidden’ crime needing to be ‘uncovered’, as it occurs in so-called ‘blind spots’, with M&S even employing a 2017 awareness-raising toolkit entitled ‘Many Eyes’ with which to ‘spot’ the issue. Similarly, the trackability, visibility, and knowability of modern slavery are also apparent in the list of source domains. Related is the metaphor of The Risk of Modern Slavery is Locatable.

The visibility and knowability of modern slavery are consistent with other mappings. The first of these describes modern slavery as a contaminant or unwanted substance that, presumably, contaminates or disrupts the product conduits and/or the locations in which workers work to maintain the flow of product. The qualitative analysis similarly reveals that all MSSs employ the modern slavery is a spreading unwanted substance metaphor systematically. The ‘spreading’ aspect of this metaphor is evident in references to modern slavery, and the crimes included under this umbrella term, as a ‘growing’, ‘deep-rooted’ issue. Such language use echoes Szörényi’s analysis of an Australian current affairs documentary TV programme, in which modern slavery is also portrayed as a contaminant.[37] The acknowledgement that modern slavery is unwanted is emphasised through the reference to these crimes as ‘issues’ in need of ‘corrective’/‘remedial action’, to be ‘eradicated’ or ‘eliminated’.

One set of metaphors that particularly relates to the understanding of modern slavery as an unwanted spreading substance, is that of a virus/stain-metaphor through references to no industry being ‘immune’ or ‘untainted’ by this crime, the need for ‘diagnosis’, and, most notably, the need to ‘[f]ocus on understanding and remediating issues and embedding the learning in [company] DNA’. [38]

It follows that, as an unwanted substance, modern slavery must be ‘eradicated’, ‘tackled’, ‘targeted’, and ‘combat[ted]’. This related mapping is responding to modern slavery is war/violence, which establishes modern slavery is an opponent/strategic target. This mapping is also very common in British news reporting on human trafficking.[39] Furthermore, this set of related systematic metaphors is also evident in the statutory guidance to the CTISC, (which, much like the MSA, also requires large manufacturers and retailers to disclose their efforts to eradicate modern slavery within their supply chains), Home Office guidance, and civil society guidance.[40] ‘Tackle’ and ‘tackling’ occur, cumulatively, with a frequency of 33 (total) in the two Home Office documents, whereas the CTISC guidance prefers ‘combat’ and ‘combating’, with a frequency of 6 (the two Home Office documents also include ‘combat’, but at a cumulative frequency of 4). Civil society guidance also uses these words, in similar ratios. This indicates some linguistic similarity between advice of the Home Office and civil society. Words with military connotations, such as ‘aim*’, ‘target*’, ‘objective*’, ‘mission*’ and ‘strateg*’ are also used in all documents.

A much more frequent systematic metaphor in MSSs is that of responding to modern slavery is a journey made of a series of steps, which is a metaphor also found in Home Office, civil society and corporate writing on this issue; the MSA itself asks for ‘a statement of the steps the organisation has taken […]’ and ‘the steps it has taken to assess and manage […] risk’. As such, MSSs may merely be mirroring the legislation’s language. All documents under scrutiny refer to ‘reasonable’, ‘immediate’, ‘next’ or ‘further’ ‘steps’ that need taking to prevent modern slavery in company supply chains, with John Lewis wanting to ‘drive’ change. These commercial retailers are further ‘guided’ by some of the Home Office and civil society publications released before and between the publication of the MSSs. The metaphor of the journey is also present in the Home Office guidance, and much more frequent than the metaphor of violence/war, with ‘step*’ occurring with a cumulative frequency of 78, compared to the 33 of ‘tackl*’. Civil society organisations such as CORE and the ETI also tend to use ‘step*’, with a cumulative frequency of 41 (compared to ‘tackl*’ at 24).[41] However, this metaphor is absent from the CTISC guidance. Nevertheless, the CTISC does use ‘eradicate’, ‘hidden’ and ‘taint’ in relation to modern slavery.

These metaphors of violence can also be found (and are equally problematic) in academic texts on the topic. For instance, in an analysis of what the term ‘modern slavery’ means, who sees it, what they see, and so on, O’Connell Davidson argues that modern slavery narratives are simplistic fairy-tale-like ones, or narratives of good and evil, and then notes that

Kevin Bales [somewhat similarly to the eradication metaphor] likens ‘modern slavery’ to smallpox, a definite condition that ‘we’ can eradicate. The disease metaphor makes powerful rhetoric, but also disregards the serious divisions that exist between those who study slavery historically, as well as those who research the phenomena dubbed ‘modern slavery’ [… T]here is no equivalent consensus on the nature, defining characteristics, and proper definition of ‘slavery’ amongst the community of researchers who study it […] Modern slavery no longer exists […] In the contemporary world, the term ‘modern slavery’ names not a thing, but a set of judgements and contentions about political authority, belonging, rights and obligations, about commodification, market and society, about what it means to be a person, and what it means to be free. As such it should be a zone of political contestation.[42]

We focused, primarily, on a small selection of MSSs that were written in response to S54 and Home Office and civil society guidance, published on behalf of/by three major high street retailers who have pro-actively engaged in debates on this topic.

Some of the metaphors we found in these MSSs indicate that, however one defines it, and whether unseen or unsightly, modern slavery is ultimately unwanted. This, in itself, is not problematic. The responses to modern slavery are also, in terms of source domain, described in a less ‘violent’ manner than the responses de/prescribed in news articles.[43] More problematic aspects of the metaphors used in the MSSs, when taken together, are of a narrative nature, as also highlighted by O’Brien: who (or what) is the villain, who is the protagonist, and who is the damsel in distress?

The main issue with these texts is that the retailers writing these MSSs have cast themselves as protagonists, or at least active, independent agents in this story, who remediate an issue that is presumed to have been, if caused by any party, caused by some other party. In this regard, it is also noteworthy that it is the company that is heroic, rather than the individual. This personification of the company has a long legal history and was indeed intended to shift responsibility for the actions of the company—or, rather, the liability for the debts and obligations of the company—away from investors and executives.[44] As such, the personification of companies in corporate discourses (and in newspaper writing) is highly conventional.[45] However, it can have effects beyond simply protecting investors’ and executives’ personal assets (as in the case of liability for corporate debts) by also distracting from those individuals who make the business decisions that end up (both unwittingly and consciously) encouraging modern slavery.

This neg(oti)ation of complicity and culpability for creating, and responsibility or even liability for remediating the risks of modern slavery, is continued through the focus on and characterisation of the supply chain and the issue as geographically spread out, as shown in both Table 1 (in relation to supply chains) and Table 2 (in relation to the risk of modern slavery). These metaphors suggest that whilst the issue of modern slavery indirectly touches these British high street retailers, it remains a geographically far-removed problem that occurs in non-Western countries in particular.[46] This portrayal of the problem as far-removed ignores the prevalence of labour exploitation and, indeed, modern slavery in parts of the supply chain that are located ‘closer to home’, let alone the potential for exploitation on the British high street itself.

Such findings indicate a simplified understanding of what modern slavery is, and what causes it. Describing modern slavery as a contaminating substance disguises human agency and glosses over the persons (both legal and natural) who exploit workers. This simplification also allows these organisations to ignore, or recast, their complicity in adopting and creating sourcing practices (of both labour and material) that leave workers in precarious, exploitable positions, and their lack of liability for creating better labour conditions.[47] These organisations are thus not encouraged to reflect on their image of ‘ethical’ actors, beyond simply adopting or accepting the label. In this regard, MSSs are, in some ways, similar to, for instance, the docufictions examined by Sharapov and Mendel, in which cases of modern slavery are portrayed as issues involving over-simplified ideal victims and offenders, wherein the ideal offender is the only party held responsible for these crimes, without consideration of issues such as agency and consent, (global) power and economic inequities, and the role of the end-consumer. As Sharapov and Mendel note, rather than improving knowledge and understanding of the issue of modern slavery, such docufictions instead are an ‘erasure of complexity—and failure to engage with the broader systemic issues that make people vulnerable—[which] helps to construct ignorance around trafficking and exploitation’.[48] Furthermore, as Sharma’s examination of responses by various parties to the (irregular) arrival of 599 Chinese migrants in Canada shows, the rhetoric around migration and trafficking is linked to a moral panic to police the global movement of the dispossessed, with no recognition of why certain people are vulnerable, and to structural causes, such as loss of livelihood and loss of security through globalisation and war.[49]

Even more worryingly, the metaphor of an unwanted, spreading substance that requires ‘eradication’ can lead to a shift of focus away from solutions that include improving labour conditions across the supply chain (and beyond), and onto solutions that entail an expulsion of those labourers who are seen as illegal, or even just those labourers who are more vulnerable to exploitation by unscrupulous suppliers, from the supply chain.[50] Simply removing these labourers from the supply chain would allow retailers to claim to have a clean supply chain. However, doing so would also increase these workers’ vulnerability and likelihood of being exploited, since it is those most vulnerable to exploitation that this metaphor suggests companies need to remove. In short, this metaphor implies a reactionary rather than preventative response to the problem of modern slavery.

This risk is further heightened by the lack of attention to workers in the supply chain, and the lack of acknowledgement of their agency and indeed humanity. There appears to be little attention to the workers who are exploited; they are mentioned, as ‘workers’; they are described as contained in the supply network (as though a substance, not people); and they are acted upon, rather than described as acting. This is consistent with work by Andrijasevic who too found that exploited bodies are portrayed as passive objects, severed from materiality, and ultimately confined within traditional positions and subjectivities.[51] This is a disenfranchising use of language to describe people, regardless of the attempts that these relatively pro-active retailers may have made to engage with workers and enable them to make their voices heard. Indeed, the continued disenfranchising of workers would also stop them from having sufficient power to not just force both buyers and suppliers to accept responsibility, but even liability, for genuinely and sustainably improving labour conditions.

As indicated, companies did, and do, not write these MSSs in a linguistic vacuum. Analysing metaphors used across the whole range of UK statutory and civil society guidance on MSSs is beyond the scope of the present study, although we have referred to metaphor use in these documents where possible. That said, our findings do suggest that these MSSs were greatly influenced by the guidance published by the Home Office and civil society organisations. The influence of popular representations of modern slavery, which suggest it must be violently responded to, is also apparent.

In other words, these metaphors are common in the texts of even ostensibly pro-active and ‘good practice’ parties. They are likely to continue being so common in these, and similar, materials, given that these are the texts of those to whom other (commercial) organisations may look for guidance or examples on writing about modern slavery. However, these texts and the metaphors within contribute to a problematic narrative on the (corporate) responsibility for (responding to) modern slavery. This is, then, also where an intervention in linguistic practices may have the greatest effect.

Our corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis of metaphors in Mothercare, M&S and JLP 2016, 2017 and 2018 MSSs revealed that, not unlike our earlier study of UK newspapers, modern slavery is once more conceptualised as a substance that spreads and must be fought.[52] Unlike our newspaper study, however, corporate responses to the issue are seen as more like a journey or a quest than a war or battle. This language has been influenced by relevant civil society and statutory guidance on modern slavery and, despite the undoubtedly good intentions of these retailers, is problematic, as it glosses over or recasts underlying factors that contribute to an increased risk of modern slavery, obscures complicity and culpability, and side-lines workers, whose agency is not acknowledged. Further to improving the level of detail in each MSS, as encouraged by the ETI, more needs to be done to encourage the adoption of a narrative and a linguistic practice that also accounts for the (systemic) causes of modern slavery, and hence addresses this problem as one that needs responding to in a truly preventative rather than merely reactionary manner.

Dr Ilse A. Ras is a Tutor in Criminology at Leiden University. She completed her PhD in English Language at the University of Leeds, holds an MSc in Criminology from the University of Leicester, and is a co-founder of the Poetics and Linguistics Association Special Interest Group on Crime Writing. Her research and teaching often cross the boundaries between English language and Criminology to examine the use of language to express, maintain and reinforce inequalities. Email: i.a.ras@live.nl

Dr Christiana Gregoriou is an Associate Professor in English Language at the University of Leeds. She researches in (critical) stylistics and crime writing. Most notable are her three monographs (Crime Fiction Migration: Crossing Languages, Cultures, Media, Bloomsbury, 2017; Language, Ideology and Identity in Serial Killer Narratives, Routledge, 2011; Deviance in Contemporary Crime Fiction, Palgrave, 2007). Her 2007 Deviance book was shortlisted for the Anthony Boucher and the Edgar Awards, under ‘Best Critical Work’. Email: c.gregoriou@leeds.ac.uk

[1] We use the term ‘modern slavery’ in this article to label the issue that corporate reports ostensibly cover in accordance with the UK Modern Slavery Act 2015. It must be noted that this term is, itself, contested and problematic. Chuang describes ‘modern slavery’ as an ‘elastic and undefined term’ that has come to encompass many different forms of exploitation through ‘exploitation creep’ (see: J A Chuang, ‘Exploitation Creep and the Unmaking of Human Trafficking Law’, The American Journal of International Law, vol. 108, issue 4, 2014, pp. 609-49, p. 628, http://doi.org/10.5305/amerjintelaw.108.4.0609). The term is problematic because it encourages ‘naming and shaming’, rather than cooperation; and it can trivialise the trans-Atlantic slave trade and other ‘historical’ forms of slavery, in turn ‘reducing any sense of responsibility for the countries that profited from [historical] slavery’, but also put a focus on exceptional and extreme forms of exploitation, which would suggest, for instance, that certain extremely abusive and exploitative (labour) practices are somehow fundamentally different from less extremely abusive and exploitative (labour) practices, and from ordinary work (see: M Dottridge, ‘Eight reasons why we shouldn’t use the term “modern slavery”’, Open Democracy, 17 October 2017, retrieved 3 June 2019, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/beyond-trafficking-and-slavery/eight-reasons-why-we-shouldn-t-use-term-modern-slavery). Chuang similarly notes that equating trafficking and slavery would mean that cases of trafficking (and exploitation) would have to be particularly severe in order to be recognised as a case of modern slavery, whilst it could also result in ‘the situation and experiences of those subject to [chattel] slavery be(ing) diminished’ (J A Chuang, 2014, p. 634). Readers are further directed to issue 5 of the Anti-Trafficking Review, in which what constitutes appropriate terminology is debated in more detail.

[2] E O’Brien, Challenging the Human Trafficking Narrative: Victims, villains, and heroes, Routledge, London, 2018; R Andrijasevic and N Mai, ‘Editorial: Trafficking (in) Representations: Understanding the recurring appeal of victimhood and slavery in neoliberal times’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 7, 2016, pp. 1-10, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121771.

[3] Andrijasevic and Mai, p. 9.

[4] G Lakoff and M Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1980.

[5] C Gregoriou and I A Ras, ‘“Call for Purge on People Traffickers”: An investigation into British newspapers’ representation of transnational human trafficking, 2000-2016’ in C Gregoriou (ed.), Representations of Transnational Human Trafficking: Present-day news media, true crime and fiction, Palgrave, London, 2018.

[6] Modern Slavery Act 2015, retrieved 2 April 2019, http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/30/introduction/enacted.

[7] G Craig, A Balch, H Lewis and L Waite, ‘Editorial Introduction: The modern slavery agenda: Policy, politics and practice’ in G Craig, A Balch, H Lewis and L Waite (eds), The Modern Slavery Agenda: Policy, politics and practice in the UK, Policy Press, Bristol, 2019, p. 8.

[8] Home Office, Transparency in supply chains etc. A practical guide, 2017, retrieved 16 April 2019, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/649906/Transparency_in_Supply_Chains_A_Practical_Guide_2017.pdf.

[9] S J New, ‘Modern Slavery and the Supply Chain: The limits of corporate social responsibility?’, Supply Chain Management, vol. 20, issue 6, 2015, pp. 697-707, https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-06-2015-0201.

[10] M Öberseder, B B Schlegelmilch and V Gruber, ‘“Why don’t Consumers Care about CSR?”: A qualitative study exploring the role of CSR in consumption decisions’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 104, no. 4, 2011, pp. 449-460, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0925-7.

[11] G LeBaron and A Rühmkorf, ‘Steering CSR through Home State Regulation: A comparison of the impact of the UK Bribery Act on global supply chain governance’, Global Policy, vol. 8, no. 3, 2017, pp. 15-28, https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12398.

[12] ETI, Our members, retrieved 15 November 2018, https://www.ethicaltrade.org/about-eti/our-members#block-views-block-member-organisations-block-1. ETI is an alliance of companies, trade unions and NGOs that promotes respect for workers’ rights.

[13] ETI and BRC, ETI & BRC letter to the PM on modern slavery, 2014, https://www.ethicaltrade.org/resources/eti-brc-letter-to-pm-modern-slavery; Marks & Spencer, M&S modern slavery statement 2015/16, 2016, retrieved 15 November 2018, https://corporate.marksandspencer.com/documents/plan-a-our-approach/mns-modern-slavery-statement-june2016.pdf.

[14] Prime Minister’s Office, UK fashion brands take action to tackle modern slavery, 2018, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-fashion-brands-take-action-to-tackle-modern-slavery.

[15] BHRRC, First Year of FTSE 100 Reports under the UK Modern Slavery Act: Towards Elimination?, 2017, https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/first-year-of-ftse-100-reports-under-the-uk-modern-slavery-act-towards-elimination.

[16] MSA, 2015.

[17] Home Office, 2017, p. 11; MSA, 2015, section 54, article 5.

[18] Sancroft and Tussell, The Sancroft-Tussell Report: Eliminating modern slavery in public procurement, 2018, https://sancroft.com/2018/03/22/the-sancroft-tussell-report-eliminating-modern-slavery-in-public-procurement/; Ergon, Reporting on Modern Slavery. The current state of disclosure – May 2016, 2016, retrieved 21 November 2018, http://ergonassociates.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Reporting-on-Modern-Slavery2-May-2016.pdf?x74739.

[19] O Johnstone, ‘First ever framework for writing “good” Modern Slavery statements produced’, Ethical Trading Initiative, 2018, https://www.ethicaltrade.org/blog/first-ever-framework-writing-good-modern-slavery-statements-produced.

[20] O’Brien, 2018.

[21] Ibid., p. 359.

[22] Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, p. 116.

[23] Ibid., p. 160.

[24] Gregoriou and Ras, 2018.

[25] C Gabrielatos and P Baker, ‘Fleeing, Sneaking, Flooding: A corpus analysis of discursive constructions of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press, 1996-2005’, Journal of English Linguistics, vol. 36, no. 1, 2008, pp. 5-38, https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424207311247.

[26] D Archer, A Wilson and P Rayson, ‘Introduction to the USAS category system’, Lancaster University, 2002, retrieved 4 April 2019, http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/usas/usas_guide.pdf.

[27] Ibid.

[28] V Koller, et al., ‘Using a Semantic Annotation Tool for the Analysis of Metaphor in Discourse’, Metaphorik.de, vol. 15, 2008, pp. 141-160.

[29] Pragglejaz Group, ‘MIP: A method for identifying metaphorically used words in discourse’, Metaphor and Symbol, vol. 22, no. 1, 2007, pp. 1-39, https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327868ms2201_1.

[30] Gregoriou and Ras, 2018.

[31] Ibid.

[32] M A K Halliday, An Introduction to Functional Grammar, 2nd ed., Edward Arnold, London, 1994.

[33] Gregoriou and Ras, 2018; O’Brien, 2018.

[34] M Anner, J Bair and J Blasi, ‘Toward Joint Liability in Global Supply Chains: Addressing the root causes of labor violations in international subcontracting networks’, Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal, vol. 35, issue 1, 2013, pp. 1-43.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Gregoriou and Ras, 2018.

[37] A Szörényi, ‘Expelling Slavery from the Nation: Representations of labour exploitation in Australia’s supply chain’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 7, 2016, pp. 79-96, p. 90, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121775.

[38] Marks & Spencer, M&S modern slavery statement 2017, 2017, https://corporate.marksandspencer.com/documents/plan-a-our-approach/mns-modern-slavery-statement-june2017.pdf; Marks & Spencer, 2016.

[39] Gregoriou and Ras, 2018.

[40] California Senate Bill No. 657, An act to add Section 1714.43 to the Civil Code, and to add Section 19547.5 to the Revenue and Taxation Code, relating to human trafficking, 2015.

[41] CORE, Beyond Compliance: Effective reporting under the Modern Slavery Act, 2016, retrieved 8 December 2018, https://corporate-responsibility.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/CSO_TISC_guidance_final_digitalversion_16.03.16.pdf; CORE, Recommended Content for a Modern Slavery Statement, 2017, https://corporate-responsibility.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Core_RecommendedcontentFINAL-1.pdf; CORE, Tackling Modern Slavery Through Human Rights Due Diligence, 2017, https://corporate-responsibility.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Core_DueDiligenceFINAL-1.pdf; ETI, Base Code Guidance: Modern slavery, 2017, https://www.ethicaltrade.org/sites/default/files/shared_resources/eti_base_code_guidance_modern_slavery_web.pdf.

[42] J O’Connell Davidson, Modern Slavery: The margins of freedom, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2015, p. 207.

[43] Gregoriou and Ras, 2018.

[44] R Breeze, Corporate Discourse, Bloomsbury, London, 2013.

[45] I A Ras, A Corpus-Assisted Critical Discourse Analysis of the Reporting on Corporate Fraud by UK Newspapers 2004-2014, PhD Thesis, University of Leeds, 2017.

[46] See also O’Brien, 2018.

[47] See also Anner et al., 2013.

[48] K Sharapov and J Mendel, ‘Trafficking in Human Beings: Made and cut to measure? Anti-trafficking docufictions and the production of anti-trafficking truths’, Cultural Sociology, vol. 12, no. 4, 2018, pp. 540-560, p. 11, https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975518788657.

[49] N Sharma, ‘Anti-Trafficking Rhetoric and the Making of a Global Apartheid’, NWSA Journal, issue 17, no. 3, 2005, pp. 88-111; See also O’Brien, 2018.

[50] Szörényi, 2016.

[51] R Andrijasevic, ‘Beautiful Dead Bodies: Gender, migration and representation in anti-trafficking campaigns’, Feminist Review, vol. 86, issue 1, 2007, pp. 24-44, https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.fr.9400355.

[52] Gregoriou and Ras, 2018.