ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

Martha Cecilia Ruiz Muriel

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, public concerns about ‘vulnerable people in street situation’ have grown in South American countries. These concerns focus on the risk of sexual violence, exploitation, and human trafficking faced by migrants and women in the sex sector. This article examines these public concerns and the discourses of risk that structure them, taking Ecuador and the border province of El Oro as a case study. It analyses how irregularised migrants and women offering sexual and erotic services talk about ‘risk’ and ‘exploitation’, and how they respond to crisis, controls, and restrictions by becoming involved in risky activities and building communities of care. These communities are solidarity alliances that connect and offer mutual support to people confronting deprivation and violence. They are not restricted to the household or the domestic sphere; rather, they constitute different forms of ‘family’ and ‘home’ building. The article is based on a participatory research in El Oro, a place with a long history of human trafficking that has not been recognised or studied.

Keywords: risk, care, pandemic, Ecuador, streetification

Suggested citation: M C Ruiz Muriel, ‘On the Streets: Deprivation, risk, and communities of care in pandemic times’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 20, 2023, pp. 33-53, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201223203

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) has been the region most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic due to pre-existing socioeconomic inequalities. Until February 2022, LAC accounted for 27.8% of all COVID-19 deaths in the world, despite having only 8.4% of the global population.[1] This disproportionate mortality rate illustrates the lethal consequences of inequality. However, the impacts of the pandemic extend beyond health concerns. The pandemic negatively impacted the economy, jobs, and personal incomes in LAC countries, while the stay-at-home orders exposed the aggravation of previous housing problems, such as overcrowding and evictions.[2] As a result, many children, elderly people, migrants transiting across the continent, and other groups in situations of vulnerability are sleeping, working, or asking for money on the streets. These experiences, referred to as ‘streetification’ (callejización) or ‘street situation’[3] are an expression of the exacerbated inequalities and conditions of precarity and abandonment in LAC.

In this article, I analyse how public concerns and discourses about ‘people in street situation’ grew during the COVID-19 pandemic and were connected to higher risks of exploitation, sexual violence, and human trafficking among ‘vulnerable populations’.[4] I focus on streetification as a process of social and spatial marginalisation in which the street becomes a place of temporary dwelling or informal work, and thus a site that denotes informalisation and precarisation, and, at the same time, as one of the multiple strategies marginalised groups deploy to fight for their lives. I concentrate on streetification in Ecuador, focusing on the street experiences of women in the sex sector and migrants with an irregularised migration status,[5] two groups that were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic and its associated restrictive measures.[6] My aim is twofold: first, to problematise dominant discourses that portray these groups as victims in need of protection and, simultaneously, as potentially risky; and second, to examine how sex workers and irregularised migrants talk about ‘risk’ and ‘exploitation’, and how they respond to crises, controls, and restrictions by becoming involved in risky activities and building communities of care.

Communities of care is a concept elaborated by Judith Butler to explain how marginalised and stigmatised groups—such as ‘sexual dissidents’ and ‘foreigners’ that have been historically linked to epidemic threat and social dangers—oppose increasing inequalities and fight against a state that erodes social services while strengthening police and military power, as we have seen during pandemic times.[7] Communities of care are new and old social networks that connect and offer mutual support to people confronting situations of deprivation and violence. These communities are not based on nuclear heteronormative families and are not restricted to the household, argues Butler: ‘they span households, they include people who are unhoused or live without a fixed shelter, who are moving from shelter to shelter, who are migratory in their lives’.[8] Thus, the notion of communities of care suggests that there are different experiences of home, housing, and shelter.

The article draws on findings of a participatory research on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the southern border of Ecuador,[9] particularly in the El Oro province, a place with a long history of human trafficking that has not been recognised or studied.

Crisis is a ‘narrative dispositive’[10] that brings to the fore some issues to debate and problems to solve (insecurity, organised crime, corruption), while side-lining others (inequality, poverty, structural violence). Therefore, crisis implies assessment and the discursive production[11] (not merely description) of certain threats and risks that explain a crisis situation and thus deserve urgent public attention, in contrast to ‘ordinary’ daily life problems. During the COVID-19 pandemic, governmental and non-governmental actors at national and international levels were highly concerned about a possible rise in human trafficking and, as a consequence, diverse programmes were introduced to tackle this problem; conversely, the aggravated problem of labour informalisation, precarisation, and exploitation attracted less public attention.[12]

Crisis and risk are understood in this article as manifestations of governmentality, that is to say, as practical interventions to regulate the conduct of individuals, collectivities, and populations, whereby ‘expert knowledge’, media, and popular discourse produce, in the first place, the peoples ‘at risk’ and ‘risky’ to be governed.[13] Scholars who adopt a governmentality approach explain that risk management implies a preventive strategy to manage the probable occurrence of undesirable behaviours and ‘disorders’ within a population. According to Aradau, as risks do not arise from the presence of a concrete danger, but exist in a virtual state and depend on arbitrary correlations, danger and risk are related to specific individuals and groups. ‘Risk practices, therefore, concern the qualitative assessment of people’, and more specifically risk profiling.[14] Aradau suggests that individuals whose ‘profiles’ combine various conditions and social characteristics that are considered sources of risk, either for themselves or for others, are categorised as ‘high risk’. This is the case of irregularised migrants involved in street-based sex work or ‘street people’ engaged in commercial sex, who are seen as trafficking victims and, consequently, governed through ambivalent policies that articulate humanitarian and security interventions.[15]

The issue of ‘street people’ (‘personas en situación de calle’) as a group considered ‘at high risk’, has been studied as part of ‘homelessness’ and ‘homeless people’—concepts that are critically examined by a growing body of literature.[16] The pathological perspective and normative framework that have guided mainstream academic literature on people dwelling on the streets are expressed in notions of ‘sickness’ (poor health and potential contagion, disability, mental illness) and ‘sin’ (sexual deviance, addiction, irresponsible parenthood, and criminality). Critical analyses question these frameworks and explain that the experiences of people dwelling on the streets are not homogeneous, and are not necessarily permanent: they can be temporal and cyclical and can combine work and begging on the streets and housing in private informal places. What connects these heterogeneous experiences is the continuous dislocation[17] of home, house, and labour due to structural conditions: weak social protection systems, socioeconomic inequalities, and labour market disadvantages based on gender, ethnicity, nationality, and migration status, among others. Likewise, engaged ethnographic researchers argue that street experiences imply physical and psychological distress, including violent policing experiences, and at the same time care relationships and forms of home and community building that are not restricted to the domestic sphere or traditional notions of household: stable, connected to a single place, etc.[18] The concept of homemaking is therefore proposed to analyse how space, affective ties, emotional states (safety, peace) and ideal conditions (economic betterment) build what people call ‘home’, and to examine how home is experienced without a stable house or home, or on the streets.[19]

The notion of streetification is still limited to the particular context of poverty and lack of social protection in the global south, and it has not been theoretically analysed. Nonetheless, it offers a conceptual vantage as it suggests the systemic processes that create the conditions for socio-spatial marginalisation and vulnerabilisation, in contrast to naturalised conceptions of vulnerability. I engage with the notion of streetification to examine the complex interplay of vulnerability-resistance.[20] Specifically, I explore how the intersection of gender, sexuality, and nationality, as axes of differentiation/hierarchisation, shape experiences of stigmatisation, irregularisation, as well as labour and housing precarity that, in turn, expose migrants and sex workers to violence and exploitation. At the same time, I consider vulnerability as a condition that has the potential for individual or collective resistance[21] and, therefore, I examine how these two groups struggle against deprivation, often on the streets, and how they influence their own experiences and life trajectories through risk-taking practices. In this idea of streetification, risk is understood as socially produced within societies that face uncertainty and inequality[22] and differently experienced by different individuals and groups, in different moments and places.[23]

The COVID-19 pandemic implied a unique situation of uncertainty and risk worldwide. Nonetheless, risk of contagion, of losing jobs, income, and shelter, or facing violence unequally affected territories and populations, as I highlight in this article.

This article is based on a participatory community-based action research. Such research offers the potential to move from ‘expert’ knowledge production and state-centred policy-making to a collaborative process of reflection and production of ideas, in which the voices and concerns of groups experiencing violence are prioritised, and the experience and knowledge of community-based actors are valorised.[24]

A local NGO working since the mid-1990s with adult and underage women affected by different forms of violence, including sexual exploitation and human trafficking, coordinated the study, with the support of two academic researchers, and two grassroots organisations (a migrant association and a sex worker network) that participated in the various stages of the research process. The objective was to better understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the dynamics of migrant smuggling, human trafficking, and other, interconnected, modes of exploitation on the southern border of Ecuador, and analyse how individuals and groups affected or at risk explain and respond to these processes. Although it was not initially guided by questions that examined the relationship between streetification and violence, exploratory interviews underlined this nexus.

An exploratory focus group with organised female sex workers, and exploratory interviews with migrants and a key informant from a support organisation, helped to refine the research objectives and questions. The research was conducted from October 2021 to March 2022 in two cities of El Oro: Machala, the province capital, and the border city of Huaquillas. It focused on and worked with adults engaged in informal, stigmatised, and unprotected work, particularly street-based work and services in ‘clandestine’ bars and brothels that were forced to close due to pandemic restrictions.

Following this, further data collection consisted of four methods, each used to triangulate and strengthen overall findings. These included: 1) peer-to-peer telephone surveys; 2) semi-structured interviews with adults engaged in unprotected work and stakeholders; 3) participant observation; and 4) content analysis.

The survey was conducted among 200 adult migrants: mainly women (70%); with irregularised migration status (91%); doing informal and unprotected work (93%), half of them involved in street-based services; and predominantly Venezuelans (80%) who have lived in Ecuador for at least one year. The survey collected data from a larger population of potential victims of trafficking and smuggling. The questionnaire was formulated collaboratively with the persons and institutions that participated in the project. Each question was discussed with the 13 migrants that conducted the survey; they tested the questionnaire and suggested some adjustments. Participants were recruited through community-based organisations.

Following the survey, 15 semi-structured interviews with people working in unprotected jobs[25] and 9 with local authorities and staff of NGOs and international agencies (IAs) that assist ‘vulnerable populations’ in El Oro, were also conducted.

In December 2021, two members of a local NGO and myself conducted participant observation at the closed border between Huaquillas (Ecuador) and Aguas Verdes (Peru). During one journey that lasted around six hours, we observed the dynamics of informal crossings—which are not new but changed drastically due to the pandemic restrictions; we crossed the few kilometres that separate these border cities, and we had informal conversations with participants in these movements. In this way, we obtained a first-hand impression of the strategies adopted by residents and migrants to access resources on the ‘other side’, or to continue their migratory projects in other countries where they intend to build a new ‘home’ away from ‘home’.

The analysis of dominant discourse on groups at/of risk was based on material obtained through interviews and reports of local and national newspapers, government documents, and the abundant publications of IAs that have mobilised their teams to El Oro to ‘aid’ migrants and refugees affected by the ‘Venezuelan crisis’.[26]

The triangulation of different data collection methods not only helped to validate the findings in terms of convergence of perspectives and trends across data. It also helped to detect differences within data, including ‘counter stories’ that disrupt master narratives,[27] and information characterised by ambiguities and grey areas between trafficking and other modes of exploitation, begging, and informal street vending. Two participatory processes of analysis interpreted these data through thematic analysis guided by categories used in the field and in critical studies on migrant smuggling and human trafficking, such as criminalisation, victimisation, precarisation, and resistance.[28]

The project followed the ethical commitments of the organisations involved and articulated in a local network created to formulate participative policies to prevent violence and assist victims.[29] This network, integrated also by local public actors, follows ethical guidelines to interview victims of violence (e.g., active informed consent), and to include their voices in reports or judicial cases, protecting privacy and confidentiality, and preventing re-victimisation. Hence, to protect the confidentiality of interviewees, I use pseudonyms, except for leaders of grassroots organisations who want to visibilise their work.

El Oro (The Gold) is a place with a long history of human trafficking and labour exploitation. During the colonial period, this region became an important supply of gold for the Spanish Empire. Hundreds of indigenous peoples and enslaved Africans worked in goldmines until they died of diseases or physical exhaustion.[30] After independence in 1830, white-mestizo elites reproduced hierarchical social and labour relations and sustained an economic model based on the exploitation of natural resources and mobile labour force.[31] This model explains the economic dynamism and, simultaneously, the social inequalities in El Oro. The province attracts internal and intraregional migrant workers to export-oriented extractive industries: gold, cocoa, shrimp, and primarily the banana market. These industries offer income opportunities but precarious labour conditions to informal workers, just like the sex and erotic markets that expanded in the province hand-in-hand with extractive economies.[32]

In Ecuador, indoor commercial sex is tolerated and regulated as a public health issue and, simultaneously, stigmatised and not recognised or protected as work. Street-based commercial sex is considered ‘clandestine prostitution’ and therefore outlawed and criminalised. During the COVID-19 crisis, however, all forms of sexual and erotic services were banned due to health concerns. Likewise, cross-border mobility was restricted to prevent the spread of the virus.

The Ecuadorian and Peruvian governments closed their shared land border for two years, from 16 March 2020 to17 February 2022. Closure of ‘non-essential’ businesses was extended until mid-2021. These restrictive measures drastically transformed daily life at the Ecuador-Peru border, which has enjoyed free circulation agreements since 1998.

The livelihoods of border populations were particularly affected by the COVID-19 restrictions. In Huaquillas, formal and informal cross-border trade represents around 80 per cent of total economic activities.[33] Traders move across the border to buy and sell, as self-employed unprotected workers, and many live hand-to-mouth. With restrictions to move and work, living conditions became extremely harsh, and outlawed activities expanded, such as informal cross-border facilitation. Likewise, migrants transiting Ecuador were severely impacted by mobility restrictions. During the first weeks of the pandemic, dozens of Venezuelan migrants were confined in border cities, with no home to stay in, and pushed to sleep in parks and other public spaces of Huaquillas and Aguas Verdes.[34]

During interviews with border residents and local authorities in Huaquillas and Machala, in late 2021 and early 2022, ‘the problem of migrants in street situation’ was still a public concern. Some expressed compassion, others described it as nuisance due to health and security issues, and many a combination of both. Several referred to children economically exploited in ‘forced begging’ and migrant women involved in ‘survival sex’ and sexually exploited. As begging and commercial sex are linked to social and legal conceptualisations of human trafficking,[35] the above-mentioned situations were assumed to be trafficking cases.[36] Others mentioned drug trafficking and consumption among those living on streets and in parks, as regularly reported in newspapers.[37] In contrast to local authorities, a trade leader recalled that the presence of migrants on the street is not new in Huaquillas. During 2019, many Venezuelan migrants got stranded in this and other border cities after Peru and Ecuador imposed visa restrictions and temporarily closed their borders.[38] Some of these migrants stayed in Huaquillas, but most headed to other countries of the Americas. The trade leader underlined the ‘dramatic’ situation of ‘foreigners’ on the streets, especially women that are perceived as victims of human trafficking and simultaneously as ‘prostitutes’: ‘White slavery (trata de blancas)[39] became a big problem in early 2020. Many Venezuelan women were desperate because they had nothing to eat. I don’t know if they were prostitutes before, in their origin country, but here they went to the streets, to corners, to sell their bodies’.[40]

IAs providing assistance to ‘vulnerable groups’ have suggested that ‘street situation’ and ‘risk situation’ go hand-in-hand.[41] They have argued that, during the pandemic, mobility restrictions and evictions aggravated the living conditions of Venezuelan migrants and refugees,[42] and, as a consequence, these groups have been more exposed to violence, including human trafficking.[43] According to IA reports and interviews with IA staff, criminal networks represent the ‘main protection risk’[44] for migrants and refugees, especially unaccompanied minors, and women who travel alone and are heads of households.[45]

IAs pay particular attention to women’s vulnerability to sexual violence, and in so doing they conflate forced prostitution, trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation, and sex work. For instance, some IA reports refer to ‘women in a situation of prostitution’ and ‘sex workers’ without distinguishing between the two or using them interchangeably;[46] they also conflate ‘sexual violence survivors’, and women involved in ‘transactional sex’.[47] By contrast, organised sex workers and leaders of migrant organisations working directly and more consistently with populations in situations of vulnerability make clearer distinctions. One of these leaders, a Venezuelan woman who participated in this and other peer-to-peer projects, explained that, during the pandemic, ‘more migrants turned to survival sex’ because they lost their jobs, income, and shelter. ‘Sex work also increased among migrants and Ecuadorians for whom this activity was their work before the pandemic. And there is also sexual exploitation, particularly against girls’.[48]

Civil society organisations also distinguish between small informal groups engaged in illicit activities and structured criminal networks. Nonetheless, the discourses of these local actors have not been as influential as the reports of IAs that offer ‘technical assistance’ on migration issues, human trafficking, and ‘border management’ to Ecuadorian authorities,[49] or the sensationalist media coverage of gangs’ criminal activities across the border.[50]

Ecuadorian authorities use the language of human rights to refer to people in ‘street situation’ and other ‘vulnerable groups’ and fund a safe shelter for adolescent victims of trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation, opened in Machala in 2008. However, governmental responses towards irregularised migrants and adult women in the sex sector have centred on controls, restrictions, and exclusionary measures. Some of these measures are expressed in the 2021 migration legislation reform, which speeds up deportations of migrants considered a ‘threat’ to public security, and introduces the concept of ‘risky migrations’,[51] which is used in public awareness campaigns on human trafficking and migrant smuggling, and to justify migration restrictions.[52]

As Deborah Lupton argues, discourse of risk has a political and moral function, and is often used to ‘blame victims’ for their irresponsible and socially unacceptable behaviour (such as working without a visa or taking children to the streets to beg or work) and thereby exert control of ‘risky bodies’.[53] This is particularly common in crisis situations that are instrumentalised to push through controls and exclusionary measures. Hence, in Huaquillas, local authorities removed unhoused migrants from public spaces like parks and ‘touristy places’ that were used as informal shelters, arguing that those spaces have turned into ‘dumps’, ‘sites for mendicity and thus delinquency’, and activities that ‘contravene morality’.[54]

During the pandemic, the Ecuadorian state apparatus was deployed at border territories through military and police agents that controlled unauthorised activities. In contrast, state protection was limited. The Emergency Family Protection Grant, that intended to cover ‘vulnerable populations’, especially informal workers, had a reduced scope and encountered difficulties in reaching unregistered populations.[55] Likewise, the temporary suspension of evictions was insufficient to prevent abuses from landlords,[56] and inspections to prevent workers’ exploitation and protect those already affected were practically non-existent,[57] despite complaints about abusive practices in formal and informal economic sectors, primarily export-oriented private enterprises.[58]

I now turn to analysing risk perceptions and risk-taking among irregularised migrants and sex workers, for whom the streets have multiple and contradictory meanings.

The language of ‘risk’ and ‘exploitation’ is also common among irregularised migrants and women in the sex sector, although with connotations that differ from those analysed in the previous section. These groups connect threats and risks to problems that affect their daily lives, such as unstable work, low income, and stigmatisation, and are seen as directly related to their nationality, gender, migration status, and the type of work they do. They also connect risk to their struggles to confront poverty and their efforts to improve their living conditions and move ahead. Phrases like ‘I took the risk’ (me arriesgué) or ‘I’ve always been a risk-taking person’ (siempre he sido arriesgada) were used during interviews to explain decisions to migrate, informal border crossings, and involvement in outlawed commercial sexual activities.

Two Ecuadorian and two Venezuelan women involved in sexual and erotic activities in Machala explained the deterioration of their economic situation and working conditions due to pandemic restrictions, and mentioned ‘harsh’ experiences of eviction and street-based work. Hence, they exposed that the spatial dimension of the pandemic has particularities when it comes to impoverished people: they could not stay at home because many lost their ‘homes’ during evictions; others turned to the streets or to ‘clandestine’ businesses to earn an income. This is how Ericka (Ecuadorian) and Gabriela (Venezuelan) explained their struggles against deprivation during pandemic times, underlining state abandonment, discrimination, and abuse from multiple actors.

In the beginning, it was impossible to work, [sex] businesses were all closed; I didn’t have savings or another source of income. We didn’t receive any help from the state or the mayor; we were discriminated against and seen as vectors of disease […]. I tried [to make a living] on the streets because I was alone with my 5-year-old child, with no money to pay the rent. I was thrown out of the house and the landlord didn’t let me take my stuff […]. Initially, police controls were strict on the streets. Then, when people started to go out, it was very hard to find something on the streets because the old girls [las antiguas, the women that have been working on the streets for a long time] were controlling some corners and they decided whether you could work there or not. The street is a tough place [la calle es dura]. (Ericka, 36)

For us [migrants], it was even worse without papers. Before [the pandemic], I was working in a bar, and from time to time I turned tricks with clients to get some extra money […]. My economic situation was okay, but I had to work day and night in the bar; it was too much exploitation. Then, with the pandemic, bars closed and for the first time I went to the street with a [girl] friend, but the police pulled us out. I didn’t have money to pay the rent so two times I was kicked out. Last time I moved with a friend, and now I have a small room for me and my two children, so I had to go back to the streets. (Gabriela, 29)

The above quotes indicate that street experiences are not restricted to houselessness or begging. They also include informal street work that, during the pandemic, became a central place to find economic opportunities, and, simultaneously, a site of instability, risk, and violence. In the phone survey, nearly half of the respondents reported experiences of violence in Ecuador, and from this group, 32 per cent mentioned violent robberies on the streets. Migrant women also mentioned sexual harassment and inappropriate touching on the streets and in workplaces (44 per cent). Home and family, far from being the idealised spaces of peace and security, were also sites of violence for participants. Nearly a third of female respondents (29 per cent) and a fifth of male respondents (19 per cent) mentioned experiences of domestic violence. Other experiences of abuse and violence were also underlined in the survey and during interviews: unjustified retention of money from private employers and bar owners, extortion from ‘gangs’ that ask for money in exchange for ‘protection’, and labour exploitation.

The experiences of violence affecting sex workers and irregularised migrants in El Oro exacerbated after the pandemic. Although they did not directly mention trafficking, probably because they were unsure about what human trafficking is, the survey and interviews revealed that they had experienced some forms of exploitation that bore resemblance to trafficking. Thirteen per cent had faced some form of coercion or duress in their work experiences in Ecuador. A much larger group—51 per cent of women and 48 per cent of men—had received ‘deceptive’ job offers. These offers included jobs with low wages and long working hours that differed from the initial agreement between respondents and employers.

The pandemic also reinforced unemployment rates and inadequate working conditions in El Oro,[59] pushing more workers to independent but unstable income-generating activities: food vending, informal clothes selling through WhatsApp, street-based sex work, and waste recycling. Those who lost their means of survival during the pandemic turned to the streets to ‘sell candies’ or ask for money (10 per cent of survey respondents[60]), activities that are not necessarily forced and expose the blurred boundaries between informal street-based work and begging. In the survey and interviews, participants avoided the notion of ‘begging’ that is associated with laziness, even among migrants. A young Venezuelan woman (23) that offers candies in exchange for money near traffic junctions, with her two small children beside her, defined this activity as ‘selling’ and ‘my work’.[61] She mentioned that revenues ‘are not so bad’ and help her from time to time with the rent costs of the small ‘leaky’ house that she shares with a Venezuelan friend.

Many impoverished migrants in El Oro were living with friends and relatives, in temporary and overcrowded or unsuitable places, before the COVID-19 outbreak, and afterwards moved to similar places. In contrast to transit migrants, who were in temporary shelters or slept on the streets, participants in this research received housing support from their social networks. The research revealed, however, that disenfranchised groups face more risks and are more likely to take risks. Working at night in unauthorised businesses where they have to hide during police raids and, in the case of irregularised migrants, and resisting border restrictions through informal border-crossings, are part of daily life experiences of risk.

The story of Gabriela illustrates how vulnerability and resistance shape the experiences of risk and risk-taking of marginalised individuals, and how they build a sense of home and family across borders. For her and other migrant women, sexuality is a site of othering and violent ordering, and, simultaneously, of resistance. Therefore, they use their eroticised ‘foreign’ bodies to access resources, and they rely on different peoples and networks to move ahead and achieve their life projects.

When I arrived in Ecuador, in March 2019, there was no visa [restriction] yet; however, the border was closed because there were massive numbers of Venezuelans trying to cross. So, I crossed by trocha [informal crossing point] with a girlfriend; we paid 20 dollars each to a guy that helped us cross. Oh, that was frightening! He took us in a big, packed truck, through some ugly paths. In Machala, I started working right away because I had a Venezuelan friend who took me to bars and brothels. It was my first time, only in Ecuador I have done this because there are no other options for us, foreigners, women, illegal, and I have to send money to my children, to my mother. […]. In the beginning, it was okay, I had some money, so I brought my children. They came with my sister and mother; they also crossed by trocha. It was risky, but I needed to have my family with me, I was missing my home. My mother went back and my sister stayed. With the pandemic, everything, work, money was gone. Thank god there were [some organisations], PLAPERTS, La Salita,[62] that helped and cared about us.[63]

Many informal workers became infected with COVID-19 in early 2020, when they went out to work or support others. This was the case of Karina. Karina Bravo, an Ecuadorian woman and internal migrant living in Machala since her early 20s, is one of the leaders of the first sex worker organisation in Ecuador and, some say, in South America: Asociación de Mujeres Trabajadoras Autónomas 22 de Junio, founded in 1982 in Machala. She is also the regional coordinator of PLAPERTS, the Latin American sex workers’ platform that has national and local chapters and played a key role in supporting women, men, and transgender people that did not receive any support from the state during the pandemic. Karina did not get public healthcare because public hospitals in El Oro and nearby cities were overcrowded and had limited resources. Therefore, she turned to her social network to receive health information and medication: doctors working with sex workers’ organisations in several Ecuadorian cities, middle-class feminist allies, organised sex workers in Machala, etc.

When other informal workers that became sick had no resources to buy food and pay the rent, or were evicted, they also received support from social networks that offered physical and virtual care. Vanesa (33), a Venezuelan migrant that received support from a local sex worker organisation that she later joined, recalled that the pandemic made her life ‘a lot harder’. The migration regularisation process was not really an option for her because visa procedures and costs are complicated and unaffordable. Therefore, she went to hotels with ‘old clients’ and she worked in ‘clandestine bars’. To feel safe, ‘cared for’ and, thus, ‘at home’, she relied on her social networks.

In those places [clandestine bars, hotels] we risk our lives. But we [sex workers] call each other to check if everything is okay, and we support each other. The first time I heard of PLAPERTS was through a neighbour. She took me to La Salita, where I received a food kit. Then I started participating in the organisation. It’s very important to be organised, you are safe. I feel more at home, supported, and I feel that they [other women in the organisation] care about me.[64]

Organised sex workers raised funds and built channels of ‘solidarity and sisterhood’ (solidaridad y sororidad) to ‘move forward’, beyond a state that ‘discriminates’ and selectively decides ‘who has the right to eat’, ‘who has the right to live’.[65] Although this and other grassroots organisations are not free of tensions and divisions,[66] during the pandemic, some of them strengthened. The support they received from local NGOs and IAs working with women and migrants was, without a doubt, essential. During the first weeks of the pandemic, and without state support, migrants, sex workers, and other informal workers largely depended on IA humanitarian programmes for survival. These programmes are, however, temporary or restricted to temporal ‘aids’ (food kits, for instance). Therefore, migrants and sex workers created peer groups and strengthened existing networks, national and regional, to share and tackle common problems, among ‘equals’, as some interviewees said.

Marginalised groups face significant stigma that translates into a deep distrust of existing structures.[67] This includes distrust of authorities, but also of service providers who, in turn, express suspicion and distrust toward stigmatised women and ‘foreigners’ that are perceived as ‘different’, ‘problematic’ or ‘aggressive’, as interviews in El Oro revealed. Therefore, migrants and sex workers create their own safe spaces and their own networks to give and receive support. In so doing, they build communities of care that, as Butler says, are solidarity alliances that develop amid capitalist inequalities.[68]

Communities of care point to something more radical than ‘resilience’ or how marginalised individuals and groups cope with deprivation and crisis situations. These ‘infrastructures of care’ imply different experiences of building home and being at home, and different experiences of household and dependency. Therefore, Lancione’s idea of dwelling as a political act of ‘difference’ is relevant here. The author explains:

[…] there is really no ‘building’ and no ‘caring’ if dwelling is just taken as a habitus, as a conserving given. In order to care and to build one needs to be ‘concerned with something’, that is, to be political about his/her own habitus of dwelling. Analytically, this means to unpack dwelling and take it as contestation.[69]

In July 2020, after four months of restrictions on movement and economic activity, and with sex and erotic businesses still closed, organised sex workers protested on the streets of Machala and demanded the ‘right to work’, and thus the opening of brothels, nightclubs, and bars. They carried banners with a clear message: ‘covid will not kill us, hunger will’. In this and other public street actions, sex workers turned the streets into a site of political struggle. That is to say, they occupied public space to claim rights, and in doing so, they contested the hierarchies and norms that structure what is considered the public and common good.[70] In this way they complicated social imaginaries about vulnerable populations as passive and voiceless and, through public protest, they showed that marginalised people not only suffer on the streets; they also struggle and build social and political alliances.[71]

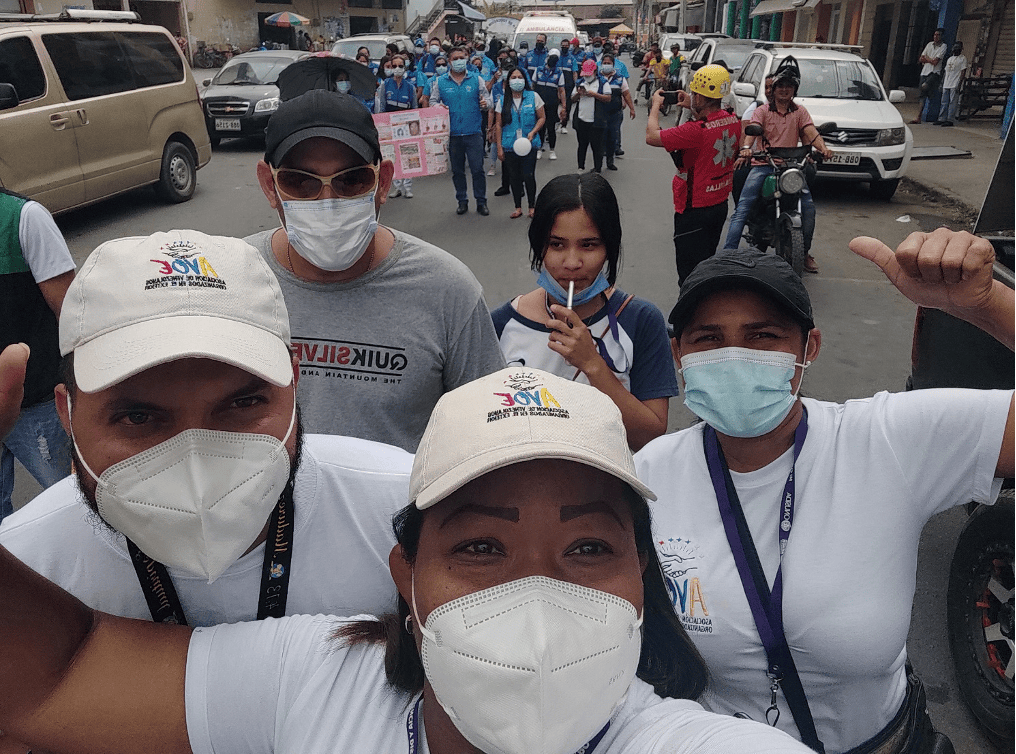

Just like sex workers’ support networks strengthened during pandemic times, so did migrant networks in El Oro and other Ecuadorian provinces. An example of this is the Association of Venezuelans Abroad (AVOE) that was founded in Huaquillas and now has branches in other cities. Magcleinmy Chirinos is one of the leaders of this network. She recalled that, although initially she did not want to participate in the organisation because she moved to Ecuador with the idea of focusing only on work, she finally decided to do so because she ‘cares’ (me importa) and she wants to ‘change things’. Caring for others and struggling to transform an unequal reality pushed Magcleinmy to the streets of Huaquillas, where she offers support to compatriots in vulnerable situations, and partakes in several projects and public activities to promote and secure migrants’ legal and social rights. This is how she explains ‘family’ and ‘home’ building among organised migrants.

We started organising because in 2019 there were already a lot of Venezuelans on the streets. I thought that although I had a lot of problems too, with work, income, and so on, at least I have a house to live in and rest. I also thought that no other organisation or institution could do better than us. We are compatriots, a family, we feel at home when we are together, and there is no one better than us to understand our problems, needs, and dreams. Organising with your peers is crucial to reach common objectives.[72]

The participatory research on which this article is based complicates common notions of ‘vulnerable people in street situation’, as well as the ‘risks’ they encounter in contexts of ‘crisis’. During the pandemic, deprived and stigmatised populations, like irregularised migrants and sex workers, were certainly exposed to greater hazards, including human trafficking and other forms of exploitation. However, these hazards cannot be explained solely with an expansion of transnational organised criminal networks or with naturalised conceptions of vulnerability that often refer to unaccompanied women. Restrictions to move and work played a central role in the configuration of ‘risks’ during pandemic times. Likewise, structural conditions of inequality, and the contradictory absence/presence (lack of social protection and simultaneously surveillance and control) of the state in El Oro and other South American border territories, both in ordinary and extraordinary times, can better explain ‘illicit’ and ‘risky’ activities in these territories.

Paying close attention to the situated experiences, narratives, perceptions, concerns, and expectations of ‘vulnerable groups’—that do not necessarily understand human trafficking in the same ways as state actors, IAs, journalists, or academics—are crucial to rethinking preconceived notions about these groups. The stories here illustrate that people experiencing a continuous dislocation of home, house, and labour build communities of care that offer material resources and emotional support, and build a sense of safety, family, and home that is not restricted to the domestic sphere or to a single and fixed place. Moreover, communities of care build political alliances and can turn the streets into a site of political struggle.

Dr Martha Cecilia Ruiz Muriel is a visiting professor at the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO) in Quito, Ecuador. She is a member of the Ecuadorian chapter of the Latin American Observatory on Human Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling (ObservaLAtrata), and a research fellow of the NGO Fundación Quimera that works on migration, human trafficking, and sex work issues in El Oro. Her research specialities include south-south migrations, borders, and intimate economies in extractive territories. Email: rmarthacecilia@hotmail.com

[1] S Cecchini et al., The Sociodemographic Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Latin America and the Caribbean, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), 2022.

[2] M M Di Virgilio, ‘Desigualdades, hábitat y vivienda en América Latina’, Nueva Sociedad, vol. 293, 2021, pp. 77–92.

[3] R4V, ‘“No Home Away from Home”: The situation of evicted Venezuelan refugees and migrants’, 2021, https://www.r4v.info/es/news/no-hay-hogar-lejos-de-casa-la-situacion-de-personas-refugiadas-y-migrantes-de-venezuela; G Herrera and G Cabezas, ‘Los tortuosos caminos de la migración venezolana en Sudamérica’, Migración y Desarrollo, vol. 18, no. 34, 2020, pp. 33–56, https://doi.org/10.35533/myd.1834.ghm.gcg.

[4] IOM Peru, Diagnóstico situacional de los delitos de trata de personas y tráfico ilícito de migrantes en la región Tumbes, IOM, Lima, 2022; R4V, 2021.

[5] I use ‘irregularised’ instead of ‘irregular’ or ‘undocumented’ to highlight that this migration status is a direct result of restrictive and selective migration policies.

[6] Global Network of Sex Work Projects and UNAIDS Joint Statement, ‘Sex workers must not be left behind in the response to COVID-19’, April 2020; G Sanchez and L Achilli, Stranded: The impacts of COVID-19 on irregular migration and migrant smuggling, European University Institute, 2020, https://doi.org/10.2870/42411.

[7] J Butler, F Zerán, and E Schneider, ‘Pandemic, Democracy, and Feminisms’, Online Dialogue, University of Chile, July 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zeaVh1EC2fQ.

[8] Ibid.

[9] The study was part of a larger project on human trafficking and migrant smuggling that was coordinated by a local NGO, Fundación Quimera, and financed by the German Agency for International Cooperation, GIZ.

[10] J Roitman, Anti-Crisis, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2014.

[11] A Hill, ‘Producing the Crisis: Human Trafficking and Humanitarian Interventions’, Women’s Studies in Communication, vol. 41, issue 4, 2018, pp. 315–319, https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2018.1544008.

[12] See the critical statement made by B Pattanaik, ‘Will Human Trafficking Increase During and After COVID-19?’, GAATW Blog, 6 August 2020, https://gaatw.org/blog/1059-will-human-trafficking-increase-during-and-after-covid-19.

[13] C Aradau, ‘The Perverse Politics of Four-letter Words: Risk and pity in the securitisation of human trafficking’, Millennium, vol. 33, issue 2, 2004, pp. 251–277, https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298040330020101.

[14] Ibid., p. 267.

[15] M C Ruiz and S Álvarez Velasco, ‘Excluir para proteger: la “guerra” contra la trata y el tráfico de migrantes y las nuevas lógicas de control migratorio en Ecuador’, Estudios sociológicos, vol. 37, issue 111, 2019, pp. 689–726, https://doi.org/10.24201/es.2019v37n111.1686.

[16] N Pleace, E O’Sullivan, and G Johnson, ‘Making Home or Making Do: A critical look at homemaking without a home’, Housing Studies, vol. 37, issue 2, 2022, pp. 315–331, https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.1929859; M Lancione, ‘Beyond Homelessness Studies’, European Journal of Homelessness, vol. 10, issue 3, 2016, pp. 163–176.

[17] Lancione, 2016.

[18] M Lancione, ‘Radical Housing: On the politics of dwelling as difference’, International Journal of Housing Policy, vol. 20, issue 2, 2020, pp. 273–289, https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2019.1611121.

[19] Pleace, O’Sullivan, and Johnson; P Boccagni, B Armanni, and C Santinello, ‘A Place Migrants Would Call Home: Open-ended constructions and social determinants over time among Ecuadorians in three European cities’, Comparative Migration Studies, vol. 9, 2021, pp. 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-021-00256-y.

[20] J Butler, Z Gambetti, and L Sabsay (eds.), Vulnerability in Resistance, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2016.

[21] Ibid.

[22] U Beck, Risk Society: Towards a new modernity, Sage, London, 1998.

[23] D Lupton and J Tulloch, ‘“Risk Is Part of Your Life”: Risk epistemologies among a group of Australians’, Sociology, vol. 36, issue 2, 2002, pp. 317–334, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038502036002005.

[24] H Hoefinger et al., ‘Community-based Responses to Negative Health Impacts of Sexual Humanitarian Anti-trafficking Policies and the Criminalization of Sex Work and Migration in the US’, Social Sciences, vol. 9, no. 1, 2019, pp. 1–30, https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9010001.

[25] These include independent activities with unstable earnings and no social security, and employees in formal markets but lacking stability and social protection.

[26] The Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V), created in 2018, publishes documents from institutions like the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR).

[27] C Cahill, ‘Participatory Data Analysis’, in S Kindon, R Pain, and M Kesby (eds.), Participatory Action Research Approaches and Methods: Connecting people, participation and place, New York, Routledge, 2007, pp. 181–187.

[28] See, for example, Ruiz and Álvarez Velasco.

[29] Red contra la explotación sexual y la trata de personas, created in Machala in 2007, and reorganised in 2015 as Mesa Técnica contra la violencia de género.

[30] V Poma Mendoza, El Oro de la conquista española, Gobierno Provincial Autónomo de El Oro, Machala, 2000.

[31] R Murillo Carrión, Zaruma, historia minera: Identidad en Portovelo, Ediciones Abya-Yala, Quito, 2000.

[32] M C Ruiz, Transacciones eróticas en la frontera sur de Ecuador, FLACSO Ecuador, Quito, 2022.

[33] Gobierno Autónomo Descentralizado de Huaquillas, Actualización del Plan de Desarrollo y Ordenamiento territorial del cantón Huaquillas, 2018.

[34] No author, ‘El drama de los extranjeros varados en línea de frontera entre Ecuador y Perú por el coronavirus’, Correo, 16 April 2020, https://diariocorreo.com.ec/41418/portada/el-drama-de-los-extranjeros-varados-en-linea-de-frontera-entre-ecuador-y-peru-por-el-coronavirus.

[35] The Ecuadorian Penal Code includes human trafficking for the purpose of ‘mendicity’, which is implicitly conceived as forced and exploited (Art. 91, 6). It also includes trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation and forced prostitution. These three are the most visibilised forms of trafficking.

[36] During 2020 and 2021, Ecuador’s official human trafficking statistics reported a drastic decrease in formally registered cases, in contrast to media and IA reports that alerted about an increase in the number of trafficked persons. Official statistics are flawed, but so are other ‘hard’ facts on human trafficking; they reflect pervasive issues with identification and reporting.

[37] C Gavilanes, ‘Venezolanos desalojados de albergue temporal’, Correo, 10 May 2021, https://www.diariocorreo.com.ec/55803/cantonal/venezolanos-desalojados-de-albergue-temporal.

[38] Herrera and Cabezas.

[39] This old term is still used in Ecuador, but ‘trafficking in persons’ is used in official documents.

[40] Interview, 16 December 2021.

[41] R4V, 2021.

[42] Ibid.

[43] R4V, COVID–19 aumenta la vulnerabilidad a la trata y el tráfico para personas refugiadas y migrantes de Venezuela: Mensajes clave para la comunidad y las personas refugiadas y migrantes, 2020, https://www.r4v.info/pt/node/4724.

[44] UNHCR, Monitoreo de Protección – Informe Región Costa, Septiembre 2021, UNHCR, p. 51; GTRM Ecuador, Evaluación Rápida Interagencial – Huaquillas, February 2021.

[45] Ibid.

[46] OEA/R4V, Impactos de la COVID-19 en personas refugiadas y migrantes de Venezuela. Personas desalojadas, trabajadoras sexuales y pueblos indígenas, 2021.

[47] R4V, Violencia basada en género. Consultas regionales a grupos con impactos desproporcionados: Necesidades y propuestas para el 2022, January 2022; CARE, Una emergencia desigual: Análisis Rápido de Género sobre la Crisis de Refugiados y Migrantes en Colombia, Ecuador, Perú y Venezuela, CARE, June 2020.

[48] Interview, 28 October 2021.

[49] Ruiz and Álvarez Velasco.

[50] No author, ‘Traiciones y deudas, causas de muertes violentas entre bandas delictivas’, Primicias, 4 April 2022, https://www.primicias.ec/noticias/en-exclusiva/traiciones-deudas-ejecuciones-bandas-delictivas-ecuador.

[51] Registro Oficial No. 386, Ley Orgánica Reformatoria de la Ley Orgánica de Movilidad Humana, February 2021, Art. 3, 15, and 143, 7.

[52] Ruiz and Álvarez Velasco.

[53] D Lupton, ‘Risk as Moral Danger: The social and political functions of risk discourse in public health’, International Journal of Health Services, vol. 23, no. 3, 1993, pp. 425–435, https://doi.org/10.2190/16AY-E2GC-DFLD-51X2.

[54] Gavilanes.

[55] M G Palacio Ludena, ‘Ecuador’s Social Policy Response to Covid-19: Expanding protection under high informality’, CRC Covid-19 Social Policy Response Series, 14, Universität Bremen, Bremen, 2021, https://doi.org/10.26092/elib/912.

[56] Ibid.

[57] There is only one public defender in charge of labour exploitation cases in El Oro.

[58] V Novillo Rameix and R Paganini, ‘Trabajadores bananeros: la explotación por la exportación’, Mutantia.Ch, 23 August 2020, https://mutantia.ch/es/trabajadores-bananeros-la-explotacion-por-la-exportacion.

[59] In this province, only 32 per cent of the population has adequate working conditions, with social security, and at least the minimum wage. ENEMDU-INEC, Indicadores laborales. IV trimestre de 2021.

[60] In contrast, only 1 per cent of those who lost their jobs mentioned sex-for-money exchanges.

[61] Some authors have studied street begging as work. See: K Swanson, ‘“Bad Mothers” and “Delinquent Children”: Unravelling anti-begging rhetoric in the Ecuadorian Andes’, Gender, Place and Culture, vol. 14, issue 6, 2007, pp. 703–720, https://doi.org/10.1080/09663690701659150.

[62] PLAPERTS (Plataforma Latinoamericana de Personas que Ejercen el Trabajo Sexual) is the Latin American Platform for People in Sex Work, and La Salita is a programme of PLAPERTS-Ecuador in Machala.

[63] Interview, 28 October 2021.

[64] Interview, 26 November 2021.

[65] PLAPERTS, ‘Manos solidarias para las trabajadoras del sexo en época de COVID-19’ [Helping Hands for Sex Workers in Times of COVID-19], 20 June 2020, https://fundrazr.com/11flL3.

[66] Among sex worker organisations, for instance, divisions sometimes take place between ‘nationals’ and ‘foreigners’, in-doors and street-based workers.

[67] International Committee on the Rights of Sex Workers in Europe, From Vulnerability to Resilience: Sex workers organising to end exploitation, ICRSE, 2021, https://www.eswalliance.org/report_on_sex_work_migration_exploitation_and_trafficking.

[68] Butler, Zerán, and Schneider.

[69] Lancione, 2020, p. 6.

[70] J Butler, ‘Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street’, European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies, 2011.

[71] Ibid.

[72] Interview, 16 December 2021.