ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

Haezreena Begum Abdul Hamid

Shelters are the most common form of assistance available to trafficked persons in Malaysia and other countries. They may offer a safe and protected environment in which they can begin their recovery and access services such as legal, medical, or psychosocial aid. However, the rules imposed in the shelters and the overall victim protection mechanisms in Malaysia have been heavily criticised for violating human rights principles. This is because ‘rescued’ victims are forcibly detained in shelters until they are repatriated, which may take months or even a year. This article considers the conditions of victims’ detention from a socio-legal perspective. Drawing upon interviews with 29 trafficked women and 12 professionals from a shelter in Kuala Lumpur, it explores the women’s living conditions and access to legal support and mental and physical healthcare within the facility. The article concludes that routine detention of trafficked persons in shelters violates fundamental principles of international law and is therefore to be considered unlawful.

Keywords: shelter homes, human trafficking, detention, detention of victims in Malaysia

Suggested citation: H B A Hamid, ‘Shelter Homes – Safe haven or prison?’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 20, 2023, pp. 111-134, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201223207

Shelter homes are the most common form of assistance available to trafficked persons in Malaysia and many other countries. In theory, shelter homes may offer a safe and protected environment in which they can begin their recovery and access a range of services such as legal, medical, and psychosocial aid in a single location. However, the rules imposed in the shelter homes, and the broader mechanisms of victim protection in Malaysia, have been heavily criticised by the United Nations and other entities for violating survivors’ human rights.[1] This is because ‘rescued’ victims are detained in government or NGO-run shelters until they are repatriated, which may take several months or even a year. Shelter detention is a common practice in Malaysia and refers to a situation where victims are unable to leave the shelter home if and when they choose to. This is stipulated in section 51 of the Anti-Trafficking and Anti-Smuggling of Migrants Act 2007 (ATIPSOM) on the mandatory requirement for (suspected) victims of trafficking to be held in shelter homes. Trafficked persons are not allowed to refuse this provision and, in some occasions, authorities assert that the victims have agreed to the restriction of their freedom of movement.[2] In cases of migrant victims, their detention is often explained as due to their legal status in the country and therefore, they should not be allowed to leave the shelter compound.[3] It is also common practice to handcuff women and make them wear uniforms.[4] Such practices are degrading and humiliating. The dualistic approach taken by the state towards trafficked persons as ‘victims to be saved’ but also as individuals that require detention and restraint has only reinforced stigma, racism, xenophobia, and victim blaming.[5]

Therefore, in this article, I consider the international legal aspects of victim detention in shelter homes from a socio-legal perspective and the reality of the term ‘protection’, which is used to conceal the detention of trafficked women in shelters. I also focus on the suitability of the shelter home as a temporary place of refuge pending victims’ repatriation to their home country. I conclude that routine detention of trafficked persons in shelters violates a number of fundamental principles of international law and is therefore to be considered unlawful and terminated.

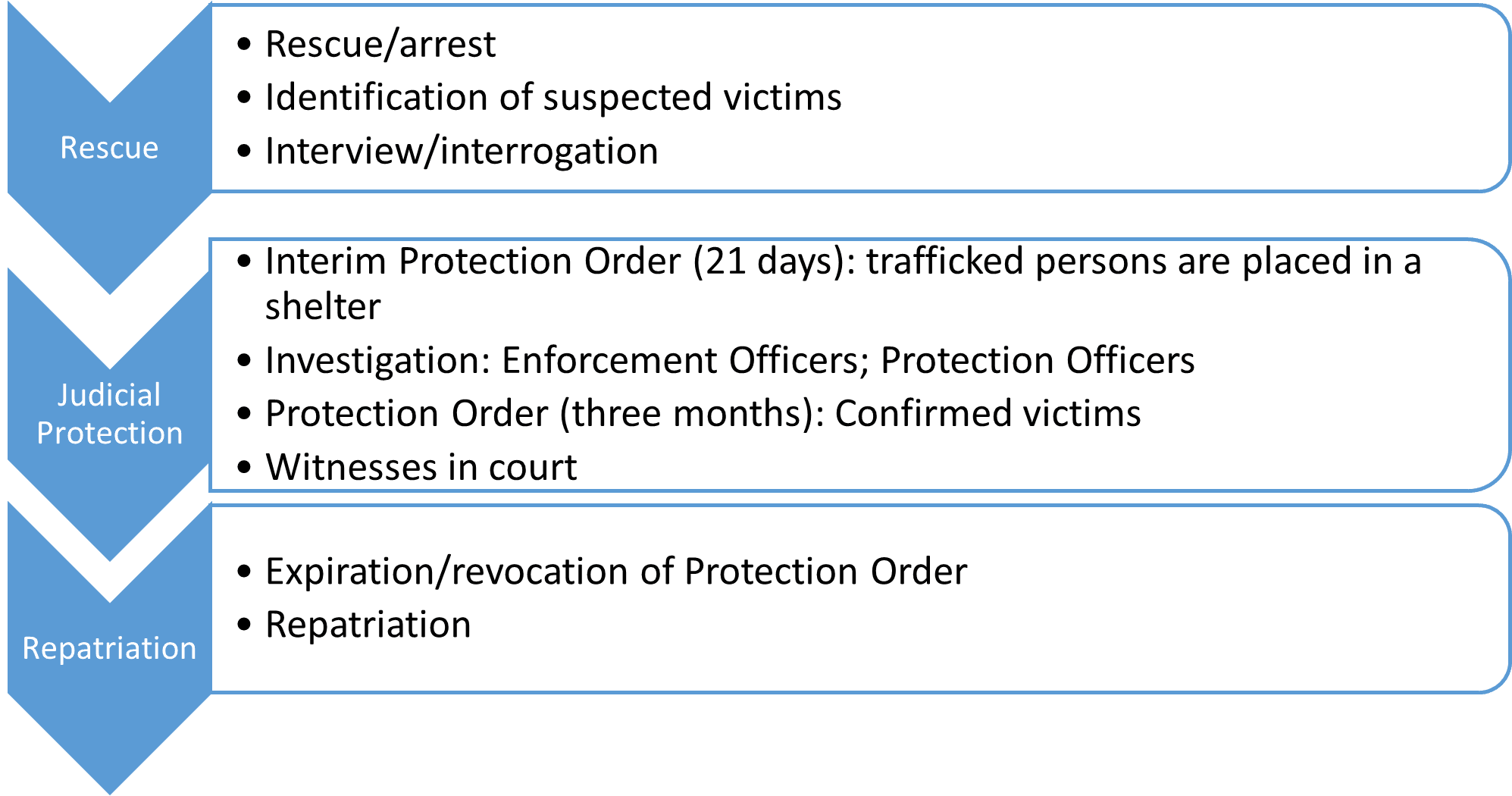

In Malaysia, men, women, and children who have been ‘rescued’ from their traffickers are detained in shelter homes, forced to undergo judicial processing, and expected to adhere to all rules and regulations before they are repatriated. These shelter homes are administered by the Ministry of Women, Family, and Community Development (Ministry of Women) and all officers working in the shelter homes are gazetted as Protection Officers which gives them the authority to protect and guard the victims. At present, there are ten shelters for trafficked persons in Malaysia: seven for women, two for children, and one for men.[6] Trafficked persons are given an initial 21-day interim protection order (for suspected victims; IPO) and a subsequent 90-day protection order (for certified victims; PO) from the courts. The period of detention may be extended by the courts to facilitate the prosecution’s case against the traffickers, since the prosecutors mainly rely on the cooperation and testimony of trafficked persons.[7] Figure 1 illustrates the standard processing of trafficked persons in Malaysia during the post-trafficking phase.

The Ministry as well as several NGOs are given the authority to operate shelter homes for survivors of trafficking. However, most are placed in government-run shelters for the purpose of security and to ensure they do not ‘abscond’ since they are potential witnesses for the prosecution. Escaping from the shelter results in an increased term of detention equal to the period of escape.[8] The law also criminalises the act of assisting trafficked persons to escape from shelters.[9]

The act of ‘rescuing’ and detaining women in shelter homes is thought to be the ‘ideal’ mode of protecting them. For example, a newspaper report considered ‘shelter homes a temporary haven for sex-trafficking victims’.[10] In reality, these ‘shelter homes’ resemble carceral institutions which restrict women’s mobility and communication and impose punitive rules and regulations.[11] They are armed with high levels of security, including barbed wire fences and security guards, which are intended to prevent women from escaping rather than to protect them from harm.[12] This clearly demonstrates the victim protection framework is carceral and paternalistic.

Gallagher as well as Lee[13] describe these shelter homes as resembling immigration detention centres and not complying with the ‘Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking’ (the Guidelines).[14] Guideline 1(6) states that all anti-trafficking measures should protect trafficked persons’ freedom of movement and should not infringe upon their rights. Guideline 6 posits that shelter provisions should not be made contingent on the willingness of the victims to give evidence in criminal proceedings and that victims should not be held in immigration detention centres, other detention facilities, or vagrant houses.

However, the Malaysian government denies that trafficked persons are subject to detention and instead assert that they have agreed to restrictions on their freedom of movement.[15] In addition, state authorities often claim that the detention of victims is necessary to secure their presence and cooperation in the criminal prosecution of their traffickers.[16] This shows how shelter homes are forced upon trafficked women and made contingent upon women testifying in court, which contravenes Guideline 6.

Shelter homes have strict regulations on issues such as admission procedures, staff conduct, termination of accommodation, handling of complaints, and administrative procedures. While these are necessary, the manner in which victims are processed is akin to how convicts are processed and detained in prison. In Malaysia, sheltered women must undergo multiple interviews or interrogations with government officials and are forced to wear uniforms, held under strict surveillance, prohibited from communicating with anyone outside the shelter, and deprived of medical, legal, translation, and psychological services.[17] As a result, women feel victimised and stressed in the shelter homes.

Non-governmental organisations, such as The Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (SUHAKAM) and Tenaganita, have criticised the human rights violations and repressive treatment which migrants and trafficked persons experience in these settings. They have raised concerns about overcrowding, poor living conditions, restriction of movement, and physical and verbal abuse towards migrants detained in shelter homes and migrant depots,[18] and have pressured the government to reform the shelter home system. SUHAKAM also urged the government to address the restricted rights of trafficked persons with the aid of civil society groups, diplomatic missions, and relevant stakeholders.[19] In response, the government has appointed a few local NGOs (Suka Society, Good Shepherd, Persatuan Salimah, and Tenaganita) to conduct various sports activities, counselling, and religious programmes in the shelters.[20] However, they are not allowed to offer legal advice to trafficked persons or change the shelter rules.[21] Even foreign embassies who are expected to coordinate with shelters on their nationals’ care and welfare do not play a significant role in ensuring that women’s rights are protected while in state custody.[22] Embassy officials are also required to obtain consent from the Director General of Women’s Development (DG) if they wish to visit their nationals in the shelters.[23] Thus, in most cases, embassies do not interfere with the shelters’ affairs or the police in order to preserve diplomatic relations.

To improve victim protection policies, the Malaysian government introduced new provisions to ATIPSOM in 2015, allowing trafficked persons to work (section 51A (1) (b)) or move freely (section 51A (1) (a)) after they have been rescued. These allow trafficked persons to work and reside outside the shelter homes. However, they are required to undergo a stringent risk assessment process, which involves security and medical examinations, and approval by the Council of Anti-Trafficking in Persons and Migrant Smuggling (MAPO).[24] Bureaucratic delays (including a lack of counsellors able to complete required mental health evaluations), risk-averse and paternalistic attitudes towards victims, as well as a lack of victim interest in available work opportunities due to low wages, have resulted in a very low number of trafficked persons being granted the right to work.[25]

Although shelter home detention is commonly justified with the need to protect victims, it is not a universal practice. In many countries, trafficked persons’ right to freedom of movement is respected,[26] and the provision of support and protection is based on genuinely informed consent. This is not the case in Malaysia where shelter detention is one of the most problematic practices.

This paper is based on interviews with 29 trafficked migrant women held in Shelter Home 5, Kuala Lumpur. I conducted the interviews between 15 April and 15 May 2016. The questions touched on their experiences of living in the shelter and the administrative process which placed them in there. I also interviewed 12 shelter professionals to gain a clearer understanding of their perception of trafficked women, policing, and protection processes. All the 29 trafficked women and the 12 professionals agreed to be interviewed voluntarily and signed a consent form.

Ethics approval was obtained from Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, prior to the interviews. I also obtained a written and verbal permission from the Deputy Director General (Deputy DG) of the Ministry of Women to access Shelter Home 5 and conduct interviews with trafficked women and shelter wardens. The process of attaining access was incredibly difficult given the levels of bureaucracy involved. However, permission was granted after the Deputy DG was convinced that the outcomes of the research would not be reported to the media and the research would be conducted based on the ‘do no harm’ principle, as contained in the ‘Ten Guiding Principles of Ethical and Safe Conduct of interviews’ advocated by the World Health Organization (the Guiding Principles). These Principles were also used as a guide in drafting the questions for the interviews, among them: to not make promises that cannot be fulfilled; to adequately select and prepare interpreters and co-workers; to ensure anonymity and confidentiality; to obtain informed consent; to listen to and respect each woman’s assessment of her situation and risks to her safety; to not re-traumatise a woman; to be prepared for emergency intervention;[27] and to use the information obtained wisely.’[28]

The trafficked women are referred to by pseudonyms, using names of their choice. They originated from Vietnam (12), Thailand (5), Indonesia (8), Laos (1), Myanmar (1), Bangladesh (1), and Nigeria (1). Their ages ranged from 18 to 44, and all were ‘rescued’ by police and immigration officials from massage parlours, brothels, entertainment centres, and private dwellings throughout Peninsular Malaysia. I interviewed twelve participants in Malay, Indonesian, or English because they could converse in those languages, while the remaining 17, who spoke either Thai or Vietnamese, were interviewed with the help of interpreters. Interpreters were carefully selected to ensure that they could interpret idioms, nuances, and metaphors during the interviews. All three interpreters were women of dual nationality—Vietnamese/Malaysian or Thai/Malaysian—and each had experience interpreting Vietnamese or Thai to English and Malay and vice versa in court proceedings. I found them through government agencies and NGOs that assist trafficked persons.

In addition to the interviews, I spent 25 days in the shelter home to observe the situation and learn about women’s experiences. During this time, I took notes of women’s activities, daily routines, and interactions with one another and the shelter staff. Among the things I recorded were the daily chores: cleaning, sweeping, mopping, drying clothes, serving food, and watering plants. I also observed the way the shelter home staff communicated with the women and how they responded to women’s questions. I noted the regular visits made by the police and officers from the Ministry. I also noted whatever I did in the shelter such as having casual conversations with the women or staff, and any incidents that occurred. In addition, I managed to take pictures of the shelter’s exterior, including the signboard attached to the gate. I was not allowed to take any pictures of the interior for security and confidentiality purposes.

The observation gave me a general idea of how women lived and were treated in the shelter. Participant observation has been used in a variety of disciplines as a tool for collecting data about people, processes, and cultures in qualitative research.[29] Through participant observation, researchers learn about the activities of the people under study in the natural setting through observing and participating in those activities.[30] In this way, I was able to learn about women’s day-to-day routines and understand the rules and regulations of the shelter as well as how women responded to them.

Shelter Home 5 began life as a spacious residential house; it is a decent-looking building in the heart of Kuala Lumpur, set back from the street and partially hidden. The house contains three bedrooms which were converted into dormitories, two bathrooms, two toilets, and a yard. There is a big lounge space where women always congregate and take short naps. There is no kitchen and only a covered dining area which is situated outside the house but within the yard.

Despite looking like a typical residential home, there are signs that Shelter Home 5 is a more carceral environment. All doors, grilles, and gates to the shelter were locked, and barbed wire was placed along the perimeters of the grounds, giving Shelter Home 5 a prison-like appearance (Images 2-3).

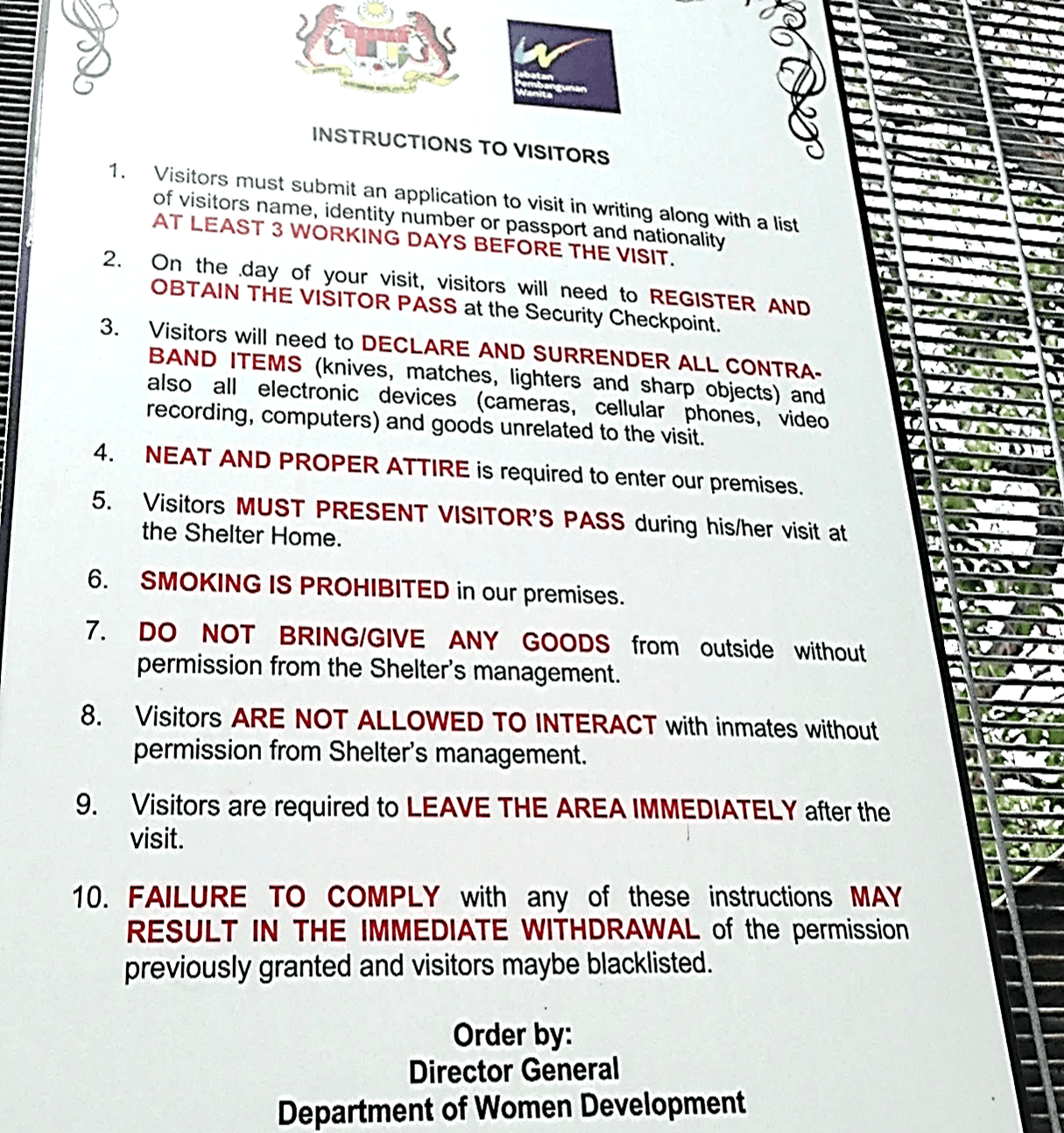

A sign attached to the main gate provides instructions to visitors. These instructions include that visitors should declare and surrender all ‘contraband’ items, including cameras, phones, and other electronic devices. Visitors are reminded to wear ‘neat and proper’ attire, and that they must not give ‘goods from outside’ to the residents without prior permission. The final rule notes that ‘failure to comply … may result in immediate withdrawal of the permission previously granted [to visit] and visitors maybe [sic] blacklisted’. As this final warning suggests, visitors could not arrive without prior authorisation. To receive authorisation, they must file an application with the DG of the Department of Women Development at least three working days prior to the planned visit. Police and protection officers, embassy officials, or pre-approved researchers were excepted. Due to the tedious process of obtaining approval, and given that most of the family members reside abroad, women do not receive any visitors other than law enforcement and protection officers. Security personnel were placed in a security house adjacent to the main gate, which could only be opened for official purposes. When asked about the reason for such measures, Shelter Home Officer Aida said it was for security purposes and to restrict the access of outsiders, particularly the traffickers.[31] However, the main reason for the tight security seemed to be to prevent women from escaping rather than to protect them from harm.[32] According to Shelter Home Officer Aznida:

The police will not bear any responsibilities once they [trafficked women] are given the Protection Order. Therefore, the women will be under our control and we have to ensure that they do not abscond.

When asked to clarify about what she meant by absconding, she said:

Some of the women do not want to be rescued but are forcedly rescued and forced to live in shelters. For example, the enforcement officers will raid a spa and arrest everyone in there. This is the standard practice in Malaysia. The police may have a good case against their perpetrators, but because they felt that they do not need to be rescued and placed in shelter, they would prefer to go off or abscond. It’s a loss for the prosecution and also would endanger the security of the shelter.

Shelter wardens often treated the women like small children, yelling at them and speaking to them in a demeaning and disrespectful way.[33] They did not entertain women’s requests for medicine, phone calls, or updates on their cases. There were also times when women’s complaints of being sick were ignored.

The shelter officers acknowledged that while some of the women were victims of trafficking, there are also some who were not ‘genuine victims.’[34] In both instances, the language used to refer to the women was disparaging. Terms such as ‘inmates’ and ‘contraband’ as well as ‘abscond’ or ‘escape’ were commonly used in the facility, both in official documents (see Image 4) and by officers. Remarks by NGO officer Cecil and Shelter Home Officer Aznida suggested that occupants on the premises were seen as offenders and that the shelter home actually resembled a prison. This reflects the dual identity women occupy as victims and offenders. Furthermore, women have to undergo certain procedures upon admission into the shelter which resemble the admission into a prison. According to Yolo:

When I first arrived [at] the shelter, I had to take off all my clothes and there was a lady who came into the toilet. There were a few of us and they checked us one by one. We were then given uniforms to wear and a number. They call us by our numbers and not our names. I was given a black t-shirt and black pants to wear when I first entered the shelter. However, I was asked to change the colour of my t-shirt to green after 21 days.[35]

Yolo’s statement shows that women were stripped naked and searched by the shelter home security officers upon admission. Such practices instil fear in the women and establish control over and subjugate them. Hutchison who conducted interviews with women in prison in Canada found that strip-searching is a form of sexual assault and harmful.[36] Women were unable to say no to being strip-searched due to power imbalances and fear of serious consequences. The very fact that strip searches are conducted on trafficked persons demonstrates state control and punishment.[37] Women were also identified by a number and not their names. As Rich notes, ‘namelessness, denial, secrets, taboo subjects, erasure, false-naming, non-naming, encoding, omission, veiling, fragmentation and lying are some of the tragic and destructive forms of silencing’.[38] Similarly, in my study, the identification of women through their numbers and not their name positioned them as nameless subjects and not as individuals who deserved to be respected.

NGO Officer Cecil responded to such practices:

This is not a detention centre, it’s not a prison, it’s a protection shelter. Therefore, the colour-coded uniforms are not necessary because it makes them feel like they are in prison, those are too much of a prison style. The women have been victimised and they have been victimised by our people [Malaysians] as well. Because our people are involved, I feel that we have to give them a better place to live in.[39]

Shelter Home Manager Ajanis acknowledged Cecil’s perception:

Victims don’t really look scared but sad when they arrive at the shelter because most of them think that this is a prison. So, we try to calm them down by telling them that this is not a prison but a shelter home.[40]

Shelter Home Officer Aznida also felt that the shelter resembled a prison:

I felt stressed out when I first started working in the shelter [seven years ago] as I felt like I was working in a prison. I used to argue with my superiors as to why women were locked up and treated like criminals.[41]

Past research considered how prison itself can cause mental health problems. According to Edgemon, overcrowded prisons lead to a higher average rate of depression, hostility, and mental health effects among prisoners, while those incarcerated in less overcrowded conditions are less depressed and hostile.[42] Overcrowded prisons also can produce worsened health outcomes, decreased psychological wellbeing, and increased risk of suicide. Such situations are also common in Malaysian shelter homes due to mandated terms of the IPOs and POs and the lack of money to build more shelters, resulting in states using existing shelters over their capacities.[43]

Shelter Home 5 was severely overcrowded. With a capacity for 70 women, it housed 202 women during my fieldwork. The overcrowding led to frequent fights amongst the women due to their confinement, causing them a lot of stress.

Emi and Putri complained about the noise and said that the shelter was always overcrowded. Putri said:

We have to tolerate the noisiness in the shelter because it is always overcrowded. No matter how many people leave the shelter, there will be new ones coming in.

This overcrowding resulted from the fortnightly police raids on massage parlours, brothels, nightclubs, and karaoke bars, which forced the shelter to accommodate more and more people.

There were only two bathrooms and toilets in the shelter, and water supply was scarce in one of the toilets. When asked about the problems faced in the shelter, some of the women complained about the shortage of food and water as well as the lack of clean water in the lavatory:

There’s not enough food for everyone here. The water supply in the lavatory is scarce and the smell is bad. It’s difficult for me to urinate or pass motion as we can only use one scoop of water. There’s only two toilets and both don’t work properly.[44]

The drinking water is yellow here. When we drink the water, we get throat problems because the water is not clean and clear.[45]

Women also complained about the shortage of food and the type of food served:

We are given three meals a day but there is always a shortage of food. It is not enough for me.[46]

I can’t eat the food here because it is too sweet.[47]

They serve instant noodles for breakfast. I am not used to eating this type of food in the morning.[48]

Although international organisations and NGOs have highlighted the poor living conditions in shelter homes, there seems to be a lack of political will to address those issues. This is because having an interest in and political will to address human trafficking will expose the magnitude and severity of corruption in Malaysia which are linked to top officials.[49] As pointed out by Aegile Fernandez, the late director of Tenaganita:

The order of the day is profits and corruption. Malaysia protects businesses, employers, and agents [not victims]—it is easier to arrest, detain, charge and deport the migrant workers so that you protect employers and businesses.[50]

According to Das, shelter homes are supposed to be spaces of rehabilitation for rescued trafficked women.[51] Their purpose is to restore victims’ rights and provide safe accommodation, counselling, and medical assistance to help them overcome their experiences of exploitation pending their repatriation. For example, in some European countries, shelter homes ‘assist victims in their physical, psychological and social recovery’. They provide, among others, appropriate and secure accommodation, psychological and material assistance, access to emergency medical treatment, translation and interpretation services, counselling and information, assistance to represent the victims’ rights during criminal proceedings against offenders, and access to education for children.[52] These services are offered to victims even if they do not choose to live in shelters. However, there appears to be no systematic approach for rehabilitating trafficked persons in most developing countries in Asia.[53] As a result, different institutions follow different approaches, depending on their subjective understanding of what constitutes rehabilitation. States determine the services and rehabilitation processes, which typically do not constitute a professional and needs-based model.[54]

In Malaysia, the term used for ‘rehabilitation’ is pemulihan which means ‘recovery’ in Malay. Essential elements of this process should include medical assessments, healthcare services, and emotional support as well as psychological and vocational counselling.[55] The process could also include uniting trafficked persons with their families.[56]

However, some of these services are either absent or nominal in Shelter Home 5. Services such as medical care and counselling are not regularly provided, if at all. Trafficked persons are not allowed to leave the shelter except to attend court hearings or go to the hospital, to which they would be escorted by the police, immigration, or protection officers. The immigration department of Malaysia does not automatically issue work permits or freedom of movement passes unless requested by the victim and approved by the Ministry of Women Affairs and MAPO. This process is lengthy and tedious and thus not popular among victims. Even maintaining contact with friends and family is difficult; the shelter homes prohibit victims from keeping their mobile phones or telecommunication gadgets while living there. Access to other areas and activities are also limited or controlled. Victims could only enter the shelter home yard for daily chores or games and activities conducted by NGOs. The games and activities usually involved drawing and colouring, and playing ball or other types of indoor games. There were also spiritual classes organised by religious groups such as Persatuan Salimah and Good Shepherd.

However, Putri and Emi stated that most women in the shelter did not participate in these activities as they considered them childish or boring.[57] Many, particularly those originating from Vietnam and Thailand, preferred to pass their time by making bracelets using plastic bags while the rest would usually congregate in the lounge and watch soap operas. To them, what was important in their recovery process was their freedom of movement, freedom to work and earn an income, and to be repatriated as soon as possible. Despite such feelings expressed by survivors, the government continues to implement those programmes and impose stringent rules in shelter homes.

All 29 of the women in my study felt helpless and disempowered because they were forced to live in the shelter against their will. They were quick to vent their anger, disappointment, and frustration towards the police as they could not understand why they were ‘rescued’ or detained in a shelter home for three months, with the possibility of having their detention extended. Many blamed the police for depriving them of the opportunity to work and support their family. For example, Liana from Kalimantan, Indonesia, said:

I can’t even see the sky in this place [cries]. They say it is a safe house but it is not a safe house because it makes people stressed out. The police are liars [cries], yes they are liars… they told me that I could go back home after 21 days but I am still here. However, I was punished to stay here for three months.[58]

Ngoc was relieved to have been rescued by the police but she had thought that she could immediately return to Vietnam; instead, she was forced to live in the shelter. She said:

I wanted the police to rescue me so that I can go back to Vietnam as I do not have a clue on how to get back to Vietnam. I hope I can go home soon as I don’t want to live here [shelter].[59]

Similarly, Mei-Mei and Hong Phan, who were not sure of the rescue process, thought that they could return to Indonesia immediately. Mei-Mei said:

The police said that they wanted to save us and send us back to Indonesia in two weeks but we are supposed to stay here [shelter] for three months before we are allowed to go home.[60]

Women also faced difficulties in accessing legal advice and were rarely given the chance to speak during court hearings. The lack of clarity and legal options while they are in custody have resulted in women becoming emotionally unstable and stressed. It appears that law enforcers were more concerned about the success of the prosecution’s case than the women’s well-being. The women said they were aggressively questioned during trials and expected to provide clear and concise evidence which could implicate their traffickers. This is very difficult for foreign women who are not provided with interpreters and thus forced to articulate their thoughts with the little Malay or English they know. Seven women complained that they did not receive enough information about the legal process. For example, Hoar An said:

The police, court, and shelter officers did not tell me why I have been detained here [shelter] for so long. I don’t know what is happening to my case and my date of repatriation.[61]

The lack of information about their court case, reasons for detention, and date of repatriation caused the women a lot of stress, confusion, and anxiety. Almost all participants stated that they felt bored in the shelter, because they were confined and did not have much to do except for some household chores:

I feel very bored because I have nothing to do here. I am so stressed out. I cry most times because I keep thinking of my family.[62]

I feel very sad living here. Nobody is able to tell me when I will be released from the shelter and would be able to go home.[63]

I feel very sad and I feel like dying. I have been in here [shelter] for two months. I don’t how long will they keep me here.[64]

These testimonies reflect the women’s sadness and uncertainty of living in the shelter. They are consistent with studies that found that imposed conditions of adversity, including prolonged detention, poor living conditions in shelters, restricted access to services, and lack of opportunities to work or study, often result in women becoming emotionally unstable, stressed, and even suicidal.[65]

Women also complained of feeling socially isolated, vulnerable, and traumatised. They were having flashbacks and found it difficult to trust people as a result of their trafficking and post-trafficking experiences. Verbal arguments and physical fights occurred frequently in the shelter home. As Hong Phan explained:

The women are always quarrelling and fighting here. I try to stay away from these fights. There is a hierarchy in this shelter and I need to respect the ‘Tai Ka Che’ (Big Sister) but I did not want to worship anyone. I just wanted to be on my own and did not want to be friends with anyone else. So, they ganged up against me and tried to find fault with me. They tried to beat me up. There were 11 of them against three of us. I feel scared now. I am scared of being bullied.[66]

This shows that there is an informal hierarchy (kingpin) system which operates to subjugate and control women in the shelter. Shelter Home Warden Lalli confirmed that there were gangs in the shelter:

There are two gangs in the shelter and they easily get into a fight if they are triggered by any issues such as spending a longer time in the bathroom or [being] given extra food. Although some of the women were arrested together, they may give opposing statements in court and so they dislike each other. Therefore, I have to try and prevent the gangs from fighting with each other.[67]

Besides the frequent fights, some women complained of psychological and emotional problems such as having nightmares[68] and seeing ‘spirits’. Ngoc said:

Some of my friends here saw a spirit in the third room. It happened to me a few times, the room right at the end of this house. It’s a female spirit who tells us the date we will be repatriated and the date we will be going home. The spirit appears in the middle of the night. There’s a rumour amongst us that there was a female who committed suicide here by hanging herself and this spirit comes to hug us.[69]

In some cases, women displayed severe signs of post-traumatic stress disorder. According to Shelter Home Manager Ajanis:

There have been few cases of post-traumatic disorder. For example, there was one lady who had OCD [Obsessive Compulsive Disorder] and used to take lots of showers. The reason why she behaved that way was because she was abused while she was working and told that she was not clean and everything she did wasn’t clean. Another example is an abuse case where the woman was tortured by the employer. She was continuously threatened by her employer and told that she will be caught by the police if she left her workplace. She has never seen her passport and became frightened when she saw her passport and said that it wasn’t hers.[70]

There were also complaints about the lack of medical care in the shelter. Only nine of the women said that they had met a doctor either in the shelter or while they were in police custody. Sixteen complained of not having enough medication, except for Panadol when they were sick and, in some cases, they were not given medicine at all. For example, Hong who had been in the shelter home for two months said:

I was examined by a doctor who came to the shelter and was told that I have a heart problem. However, I have not been given any medicine till now.[71]

Nisa said:

I had an operation [the] day before yesterday. The doctor cleaned my vagina and anus because I had too much discharge. I am still in pain and there is white liquid coming out of my vagina. The doctor gave me some medicine but it has finished. I told the shelter officers but they only gave me Panadol which did not help to alleviate the pain.[72]

Shelter staff confirmed that there were no medical professionals in the shelter. Because women are not medically screened before entering the shelter, the shelter home officers were unaware of any existing illnesses the women had.[73] However, the shelter staff perform physical checkups to try to identify any marks or suspected illnesses. According to Shelter Home Officer Aida:

We need to check if they [the women] have any illnesses, burn marks, or bruises when they first enter into the shelter. We use gloves when we perform checkups as we are afraid of contracting any disease. We identified two HIV cases from the checkups. In one particular case, the woman was very thin and had a lot of ringworms near the breast line. We asked her if she had AIDS to which she kept quiet. We informed the police and she was taken to a hospital for further checkups. She died less than a week after that at the Sungai Buloh Hospital.[74]

Women will only be sent for hospital visits if they are suspected to have severe and advanced stage of illnesses. Despite the admission on the lack of facilities and poor living conditions by the shelter home manager, there have not been any attempts to improve the situation because of the limited budget allocated to the shelter homes.[75] According to Shelter Home Officer Aida:

The person who is in charge of us at JPW [Department for Women’s Development] is not aware of the work we do. It is so difficult for them to give us the budget, even during critical times. We are only given MYR 20,000 (USD 4,489) per month which is not even enough to cover the women’s expenses. One track pants costs MYR 30 (USD 6.70) and if there are 200 women here, I will need to provide 400 pants for them because we give them two sets each. There are also other items that we need to purchase such as toothbrushes, shampoo, soap, towels, and detergents, and it all has to be covered with the budget of MYR 20,000 per month.[76]

The experiences of the women living in the shelter provided some insight into how it operates and the adverse impacts on the women. Despite the intention of protecting women from their traffickers, prolonged detention often resulted in women becoming emotionally unstable and stressed. However, little attention is given to such consequences because the government is focused on combating human trafficking by prosecuting offenders.[77] Given this, the government does not want to be seen as assisting women who are involved in sex work or allocating extra funds to improve their living conditions while in detention.[78] As a result, migrant women are forced to live in sub-standard shelter homes and are exposed to physical and psychological harms.

Women in Shelter Home 5 described living in prison-like conditions despite being classified as victims of trafficking. They struggled with a lack of autonomy and control over their own lives, including their ability to keep in contact with friends and family members. They were also frustrated by the lack of services, especially legal and psychological aid, finding little value in arts and crafts or spirituality programmes. These findings echo those of other research that shows clear parallels between the experience of trafficked persons in semi-carceral institutions like shelter homes and those in immigration detention and prisons.[79] Trafficked women are categorised as victims and they deserve to be treated with humanity and respect. However, Malaysia’s current shelter home system is extremely unsatisfactory, due to the limited space and poor living conditions, repressive rules, limited activities on offer, and the lack of medical care and counselling for victims.

Unlike prisoners or detainees, however, the experiences of trafficked persons in shelter homes are underreported and understudied. Their stated aim of offering ‘protection’ to victims places shelter homes above scrutiny.[80] While some countries follow the so-called 3Rs—rescue, rehabilitation, and reintegration—the Malaysian practice more adequately resembles rescue, detention, and repatriation. In detention, women’s rights to freedom of speech, freedom of movement and residence, and free choice of employment are severely curtailed. These practices are at odds with ATIPSOM, which prohibits women’s incarceration pending their repatriation, and Guideline 6 of the Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking, which recommends that states provide adequate legal, medical, and psychological care for trafficked persons.

These prison-like conditions and the absence of services put the women in shelter homes at risk of exploitation and poor health. Without legal representation, they are unaware of their rights, do not understand their legal status, and presume that they are serving a prison sentence. Additionally, the overcrowding, stress, and poor food and hygiene all contribute to physical and mental health issues that can manifest as depression, self-harm, or suicidal ideation. Shelter homes, far from protecting survivors of trafficking, sustain the causes of women’s social subordination, including those that stem from sexism, xenophobia, and racism.[81] Such shelter homes exist as part of the broader ‘raid-and-rescue’ approach to trafficking that penalises migrant women, particularly those engaged in sex work. These carceral anti-trafficking measures stigmatise, marginalise, and criminalise sex workers and migrants on the grounds of security.[82] They also assume that the best solution to human trafficking is law enforcement and prosecution. However, as human rights advocates note, this prosecution-first approach ignores systemic weaknesses in the justice process that fail to hold perpetrators accountable. These advocates add that while law enforcement efforts are important for reducing human trafficking, it is even more important to address the root causes, such as corruption and exploitative labour migration schemes.[83]

The 2021 and 2022 TIP Reports, which placed Malaysia in Tier 3,[84] recommended that the government improve its victim protection practices, including the consistent use of interpreters, allowing survivors to communicate with people outside shelters, increasing their freedom of movement from shelters, and eliminating the use of chaperones. More broadly, the government must ensure that all state-led anti-trafficking measures adhere fully to the Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking. With respect to protection, this means that trafficked persons should not be held in detention centres or vagrant houses and should be afforded services that are not contingent on their willingness to give evidence in criminal proceedings. Adequate support to trafficked persons, and their treatment with respect and dignity, must be an indelible part of a good anti-trafficking response.

At present, the policies of rescue, detention and repatriation that are brought forth to ‘save victims’ violate women’s rights to freedom of speech, freedom of movement and residence, and free choice of employment. Therefore, immediate improvements are needed to address such human rights violations. This includes the abolishment of forced detention in shelter homes and making shelters more comfortable for those trafficked persons who require refuge. This would include bigger living space; access to light, sun, clean air, and hygiene; and respectful, professional staff. Trafficked persons should also be provided with assistance and information about their cases, legal advice regarding the court processes and compensation, as well as counselling. These improvements can create an environment more conducive to trafficked person’s health and well-being, thereby assisting them in their recovery. Through providing sufficient victim support and prioritising the needs of victims, the state would be able to reduce crime and promote its crime prevention strategy in combatting human trafficking.

Dr Haezreena Begum Abdul Hamid is a Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Law at the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur. She obtained a PhD in Criminology from Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, and was a practising lawyer in the Malaysian courts for 17 years. Her areas of interests include human trafficking, criminology, victimology, sexual crimes, policing, international crimes, and human rights. Email: haezreena@um.edu.my

[1] A T Gallagher and E Pearson, ‘The High Cost of Freedom: A legal and policy analysis of shelter detention for victims of trafficking’, Human Rights Quarterly, vol. 32, no. 1, 2010, pp. 73–114, https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.0.0136; L Lyons and M Ford, ‘Trafficking Versus Smuggling: Malaysia’s Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act’, in S Yea (ed.), Human Trafficking in Asia: Forcing issues, Routledge, London, 2014.

[2] A T Gallagher and E Pearson, ‘Detention of Trafficked Persons in Shelters: A legal and policy analysis’, SSRN Papers, 1 November 2008, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1239745.

[3] Ibid.

[4] A Miller, ‘Sexuality, Violence Against Women, and Human Rights: Women make demands and ladies get protection’, Health and Human Rights, vol. 7, no. 2, 2004, pp. 16–47, https://doi.org/10.2307/4065347.

[5] M C Desyllas, ‘A Critique of the Global Trafficking Discourse and U.S. Policy’, Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, vol. 34, issue 4, 2007, pp. 57–79.

[6] The Star, ‘Eradicating Human Trafficking, Smuggling Activities’, The Star, 2 August 2021, https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2021/08/02/eradicating-human-trafficking-smuggling-activities.

[7] US Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report 2016 - Malaysia, Washington DC, 2016.

[8] S.55(b) ATIPSOM.

[9] S.56 ATIPSOM.

[10] J Edward, ‘Shelter Homes a Temporary Haven for Sex-trafficking Victims’, Malaymail, 18 April 2016, https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2016/04/18/shelter-homes-a-temporary-haven-for-sex-trafficking-victims/1102061.

[11] Gallagher and Pearson, 2010.

[12] United Nations Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Maria Grazia Giammarinaro: Mission to Malaysia, A/HRC/29/38/Add.1, 1 June 2015; US Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report 2012 - Malaysia, Washington DC, 2012.

[13] M Lee, ‘Gendered Discipline and Protective Custody of Trafficking Victims in Asia’, Punishment and Society, vol. 16, issue 2, 2014, pp. 206–222, https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474513517019.

[14] Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking, United Nations, 2003, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Publications/Traffickingen.pdf.

[15] Gallagher and Pearson, 2010.

[16] Ibid., p. 74.

[17] Lee.

[18] See: Suhakam, http://www.suhakam.org.my; No author, ‘TENAGANITA: The Truth About Migrants in Malaysia’, Women’s Aid Organisation, 9 May 2012, https://wao.org.my/tenaganita-the-truth-about-migrants-in-malaysia.

[19] A Yunus, ‘Suhakam: Significant improvement needed after Malaysia sinks to lowest ever ranking in human trafficking report’, The Star, 22 June 2014, https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2014/06/22/suhakam-anti-trafficking-report.

[20] No author, ‘Protecting Trafficked Survivors’, SUKA Society, 2015, retrieved 7 October 2015, http://www.sukasociety.org/protecting-trafficked-survivors; US Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report 2021 - Malaysia, Washington DC, 2021.

[21] US Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report 2017 - Malaysia, Washington DC, 2017.

[22] US Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report 2014 - Malaysia, Washington DC, 2014.

[23] Ibid.

[24] S.51A(2), ATIPSOM.

[25] US Department of State, 2017.

[26] Shelters are open and victims are free to come and go as they please. See: Gallagher and Pearson, 2010.

[27] This means for the interviewer to be prepared to respond if a woman says she is in imminent danger.

[28] C Zimmerman and C Watts, WHO Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Interviewing Trafficked Women, World Health Organization, Geneva, 2003, p. 4.

[29] B B Kawulich, ‘Participant Observation as a Data Collection Method’, Forum: Qualitative Social Research, vol. 6, no. 2, 2005, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-6.2.466.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Which may not be very likely, given what the women had told me about their traffickers. See: H Hamid, ‘Sex Traffickers: Friend or foe?’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 18, 2022, pp. 87–102, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201222186.

[32] United Nations Human Rights Council; US Department of State, 2012, 2014.

[33] For more on shelter staff treating survivors with disrespect and suspicion, see D Bose, ‘“There Are No Victims Here”: Ethnography of a reintegration shelter for survivors of trafficking in Bangladesh’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 10, 2018, pp. 139–154, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201218109.

[34] Interview, 27 April 2016.

[35] Interview, 25 April 2016. Women who are given an IPO (i.e., suspected victims) wore black uniforms and women who had obtained a PO (i.e., confirmed victims) wore a white uniform. Red, green, and orange-coloured t-shirts represented the colour of the dorm they belonged to.

[36] J Hutchison, ‘“It’s Sexual Assault. It’s Barbaric”: Strip searching in women’s prisons as state-inflicted sexual assault’, Affilia, vol. 35, issue 2, 2020, pp. 160–176, https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109919878274.

[37] D Kilroy, ‘Strip-searching: Stop the state’s sexual assault of women in prison’, Journal of Prisoners on Prisons, vol. 12, 2003, pp. 30–43, https://doi.org/10.18192/jpp.v12i0.5469.

[38] A Rich, ‘The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action (A Panel Discussion)’, Sinister Wisdom, vol. 6, no. 1, 1978, pp. 17–25, p. 18.

[39] Interview, 13 May 2016.

[40] Interview, 29 April 2016.

[41] Interview, 27 April 2016.

[42] No author, ‘Auburn Criminology Expert Explains How Prison Conditions Affect Mental Health’, 21 September 2022, retrieved 18 January 2023, https://ocm.auburn.edu/experts/2022/09/200920-edgemon-prison-mental-health-ea.php.

[43] US Department of State, 2021.

[44] Interview with Putri, 20 April 2016.

[45] Interview with Yolo, 25 April 2016.

[46] Interview with Musa, 22 April 2016.

[47] Interview with Mon, 9 May 2016.

[48] Interview with Mei–Mei, 11 May 2016.

[49] K Hodal, ‘US Penalises Malaysia for Shameful Human Trafficking Record’, The Guardian, 12 December 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/jun/20/malaysia-us-human-trafficking-persons-report.

[50] Ibid.

[51] B Das, ‘Rescue by “Force” or Rescue by “Choice”’, Open Democracy, 25 November 2017, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/beyond-trafficking-and-slavery/rescue-by-force-or-rescue-by-choice.

[52] R Surtees, Why Shelters? Considering residential approaches to assistance, NEXUS Institute, Vienna, 2008

[53] ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, Rehabilitation of the Victims of Child Trafficking: A multidisciplinary approach, International Labour Office, Bangkok, 2006.

[54] Ibid.

[55] USAID, The Rehabilitation of Victims of Trafficking in Group Residential Facilities in Foreign Countries: A study conducted pursuant to the Trafficking Victim Protection Reauthorization Act, USAID, 2005.

[56] R Surtees and L S Johnson, Pemulihan dan Penyatuan Semula Pemerdagangan Mangsa: Panduan pelaksana, Regional Support Office of the Bali Process and Nexus Institute, Bangkok, 2021

[57] Interview with Putri, 23 April 2016, and Emi, 22 April 2016.

[58] Interview, 23 April 2016.

[59] Interview, 28 April 2016.

[60] Interview, 11 May 2016.

[61] Interview, 26 April 2016.

[62] Interview with Efa, 25 April 2016.

[63] Interview with Fon, 30 April 2016.

[64] Interview with Musa, 22 April 2016.

[65] D Silove, P Ventevogel, and S Rees, ‘The Contemporary Refugee Crisis: An overview of mental health challenges’, World Psychiatry, vol. 16, no. 2, 2017, pp. 130–139, https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20438; No author, ‘Hyderabad: Rescued Uzbek woman ends life in shelter home’, Deccan Chronicle, 15 April 2018, https://www.deccanchronicle.com/nation/crime/150418/hyderabad-rescued-uzbek-woman-ends-life-in-shelter-home.html.

[66] Interview, 29 April 2016.

[67] Interview, 13 May 2016.

[68] S Huda, ‘Sex Trafficking in South Asia’, International Journal Gynecology & Obstetrics, vol. 94, no. 3, 2006, pp. 374–381, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.04.027.

[69] Interview, 28 April 2016.

[70] Interview, 29 April 2016.

[71] Interview, 28 April 2016.

[72] Interview, 3 May 2016.

[73] Interview with Shelter Home Manager Ajanis, 29 April 2016.

[74] Interview, 10 May 2016.

[75] Interview with Shelter Home Officer Aznida, 27 April 2016.

[76] Interview, 10 May 2016.

[77] S-Y Cho, ‘Evaluating Policies Against Human Trafficking Worldwide: An overview and review of the 3P index’, Journal of Human Trafficking, vol. 1, issue 1, 2015, pp. 86–99, https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2015.1014660.

[78] Interview with Shelter Home Manager Ajanis, 29 April 2016.

[79] M Bosworth, ‘Immigration Detention in Britain’, in M Lee (ed.), Human Trafficking, Willan, London, 2007; Gallagher and Pearson, 2010; Lee.

[80] Lee.

[81] G Samari, A Nagle, and K Coleman-Minahan, ‘Measuring Structural Xenophobia: US state immigration policy climates over ten years’, SSM Population Health, vol. 16, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100938.

[82] C Murray, ‘Ending the Stigma Surrounding Human Trafficking: Series introduction’, See the Triumph, 3 June 2014, retrieved 26 March 2022, http://www.seethetriumph.org/blog/ending-the-stigma-surrounding-human-trafficking-series-introduction.

[83] R R Ganesan, ‘No Excuse for Poor Standing in Human Trafficking Report, Hamzah Told’, Free Malaysia Today, 6 August 2022, https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2022/08/06/no-excuse-for-poor-standing-in-human-trafficking-report-hamzah-told.

[84] Tier 3 is the lowest ranking, which indicates countries whose governments do not fully comply with the minimum standards to combat human trafficking and are not making significant efforts to do so.